Growing up in a suburb of Los Angeles, I did not have the immediate knowledge of where our food and water came from. I turned on the faucet for water, plugged cords into the wall for electricity and went to the store for food. Yes, my city had been engineered for me and I was mindlessly playing my role.

At a young age I felt that there was something wrong with my ignorance. Even worse, no one else seemed to be aware of our unawareness. Everything came from ‘somewhere else’. One comfort for me was that my mother grew up on a farm and she would tell tales of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl where many people had no food and some even starved to death. My mother’s family were poor by most standards, but they had 51 acres of land in rural Ohio and they fed themselves and many others. My mother’s stories inspired me to become an ethno-botanist to learn about how plants were used in the past.

Though I did not pursue the path of ‘urban planning’ and knew I would never be engineering my city or any city, I realised that I had many choices within the framework of my suburban life where I could ecologically engineer my life.

Personal Choices

My first teenage forays were into backyard urban gardening and raising chickens in a tiny space. I didn’t want to be dependent on produce that was full of commercial fertilisers and bug-sprays so I learned the ages-old methods of agriculture, methods that people today call ‘organic’ or ‘perma-culture’. I learned that anyone could indeed produce at least some of their food in the least amount of space.

Even in my late teenage years, I had critics who told me it was not practical to grow foods without artificial fertilisers and pesticides. Really? I followed the path of Fusuoka and his ‘One Straw Revolution’, and the Rodale family, and insisted on growing everything with nothing artificial. I learned to keep the bug population down using natural methods that had been practiced worldwide for millennia. I knew that the socalled Green Revolution, founded on petroleumbased fertilisers and pesticides, was partly a fraud and was not sustainable into the future.

We can solve many of our problems today by looking to the past for some of the solutions

I continued my botanical studies by learning about the uses of wild plants of the Native Americans. I realised, to my surprise, that all the foods used by the indigenous population could still be found throughout my homeland, though it was necessary to hunt a bit more because of all the houses, roads and modern landscaping that has taken over the land. Yes, the engineering of the concrete city has destroyed much of the territory for these native foods, but they were not entirely gone.

I began to eat these wild plants that had sustained people for centuries and I incorporated them into my regular diet. When I first began to share my excitement of these floral treasures with others, I was treated with mostly apathy, sometimes scorn and even pity. I was amazed!

Bottom Left: This is a neighbourhood garden, found in many cities, where you can rent a plot and grow vegetables

Bottom Right: Oscar Duardo runs a neighbourhood garden not far from downtown Los Angeles. He is standing next to an amaranth patch

Re-Engineering My Own Mind

In the mid-1970s in Los Angeles County, I began publicly teaching and writing about the practical skills of self-reliance and realistic survival in the city. I was not engineering the city, but I was working to engineer a new mindset that says we can live ecologically (and economically) in the city.

Today, there is a renaissance and a great interest in the knowledge of our ancestors. And it’s never too late to begin to seek our roots and to turn around some of the bad habits of ecological suicide. I believe that we can solve many of our problems today by looking to the past for some of the solutions.

Here in Southern California, we have just had over a four-year drought, which has finally inspired politicians and water department movers and shakers to encourage the millions of people who live here to consume less water. With water usage averaging about 131 gallons per person, per day for Los Angeles residents and an ever-growing population of about 5% a year, water must always be a concern, as it will always be for most major cities of the world.

Right: A garden can be grown in any small area, as illustrated in this small front yard garden

The mayor of Los Angeles and water department officials are encouraging people to tear out their lawns and install drought-tolerant plantings. I encourage people to go one step further. Actually, a few steps further. Yes, learn about the wild plants, which are edible and medicinal. They will grow without your care. And never merely plant ‘ornamentals’ i.e. plants that do not provide food, medicine or good mulch from their leaves. Plant with a purpose to feed your body and your soul.

To help irrigate these useful plants, I’m a big proponent of simple grey-water recycling, where your sink and washing machine water are piped into your backyard garden or front yard orchard. Not every single city dweller can do this, but enough can do it to make a large difference. Yes, certain changes are essential, such as buying soaps that contain no dyes, colours or harmful chemicals. Continuing education is a big part of self-reliance and sustainability. Recycling your grey-water means that you are getting at least two uses from water, which was previously used only once. Practically speaking, for every gallon of water you recycle, you have effectively created another gallon of water for your use, which does not have to be imported from somewhere else.

There is a growing need for more food and more water as a function of increased population. This unfortunately means even more land paved over for more houses or apartments. Thus, the very soil that all ancient civilisations knew was the foundation of a healthy society becomes more and more rare. This should not be the case, even though it seems all but inevitable.

Our very lifeblood is dependent on the soil in so many ways: for water, food and much more. However, urban people need to re-learn these very basic ecological principles. Our very laws and attitudes – especially in the more ‘developed’ countries – work against our long-term sustainability.

Top Right: A view of a neighbourhood garden

Bottom Right: Where the conditions are right, bees can be kept in the city

Urban Sustainability

The green lawn is still the norm in the sprawling suburban flatlands of Southern California. Neverending flowing of water (from somewhere) is the expectation everyone has. The mindset must turn around and it will begin with enlightened individuals who see that inappropriate lifestyles in an over-populated dry terrain are the antithesis of survival. As attitudes change – and slowly they are – the laws of the land need to support the water-wise practices that support sustainability.

As a lifelong-educator in the uses of common wild plants, I cringe when I see television advertisements for such products as Roundup and others designed to kill off the ‘unwanted vegetation’ of urban gardens and landscapes. These are plants such as dandelions and other healthful herbs called ‘weeds’.

To me, a student of wild plants and things growing in the faraway and neglected places, using a chemical like Roundup to ‘clean up’ a wild area is sacrilege. Bankers and land investors do not necessarily see the land as a source of life, recreation, fulfillment and community. Rather, increasingly, the desire is to extract the greatest financial benefit from the land. Land that has nothing built upon it is all too often described as ‘non-performing real estate’. That is the mentality that has caused the urban sprawl to spread even further, while diminishing the very sustainability from the land that we all need. ‘Engineering’ the city should not be simply building ever-more structures on a diminishing landscape. We should be re-engineering our thinking so we can get more from less, in ways that are both healthful and ecological.

For every gallon of water you recycle, you have effectively created another gallon of water for your use

The Quiet Revolution

I am a pioneer of the path of the green and sustainable revolution. You won’t find me protesting in the streets for changes, but you might find me in a city council meeting. I work with people one at a time. I have found that once an individual understands that the so called weeds in an empty field are actually great nutritious food or medicine, they suddenly take a very personal interest in protecting the land.

Once individuals learn that the water from their very households can water their own garden and herb-patch, they become quite alert and aware of the quality of any soaps they are using and they begin to use only those that are biodegradable, as a result of enlightened selfinterest. Suddenly, living an ecological urban life becomes very personal.

There are many paths to urban sustainability. This is the path I have chosen.

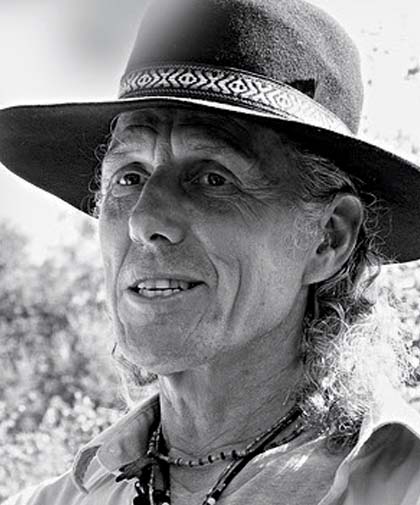

Christopher Nyerges works to engineer a new mindset that says we can live ecologically (and economically) in the city. He has taught self-reliance and sustainability his entire life through the teaching of ethnobotany and principles of permaculture. Nyerges is the author of 17 books. He is the founder of the School of Self-Reliance and works actively with various nonprofits for the goals of urban sustainability. He can be reached, for questions or information about his books and classes, at christopher_nyerges@yahoo.com

All photos: Christopher Nyerges

Comments (0)