Picture this: Le Corbusier’s “machine for living in” left to rust like an abandoned car. That’s how architect Bernard Tschumi encountered Villa Savoye when he was a student. The young pilgrim found a heap in place of the promised holy site. And yet, recollecting his architectural hajj, he muses, “the Villa Savoye was never so moving as when plaster fell off its concrete blocks.” The building had fallen into disrepair and failed Corbu’s lofty functionalist ambitions, but by aging in place it achieved a fullness of being that its designer could not have predicted nor controlled. In Architecture and Transgression (1976), Tschumi remarks that the villa’s decay reveals modernism’s “refusal to recognize the passing of time.” The problem of new-ness is even more pronounced in green design, which increasingly emphasises high-tech solutions that require active maintenance and monitoring. Like Villa Savoye, these features aren’t designed to adapt and evolve. Green tech is usually hidden or looks superficial, which means sustainability as an architectural idea is seldom expressed as a coherent aesthetic. Sustainability needs a style that can allow places to age and function gracefully. One possibility is the Picturesque.

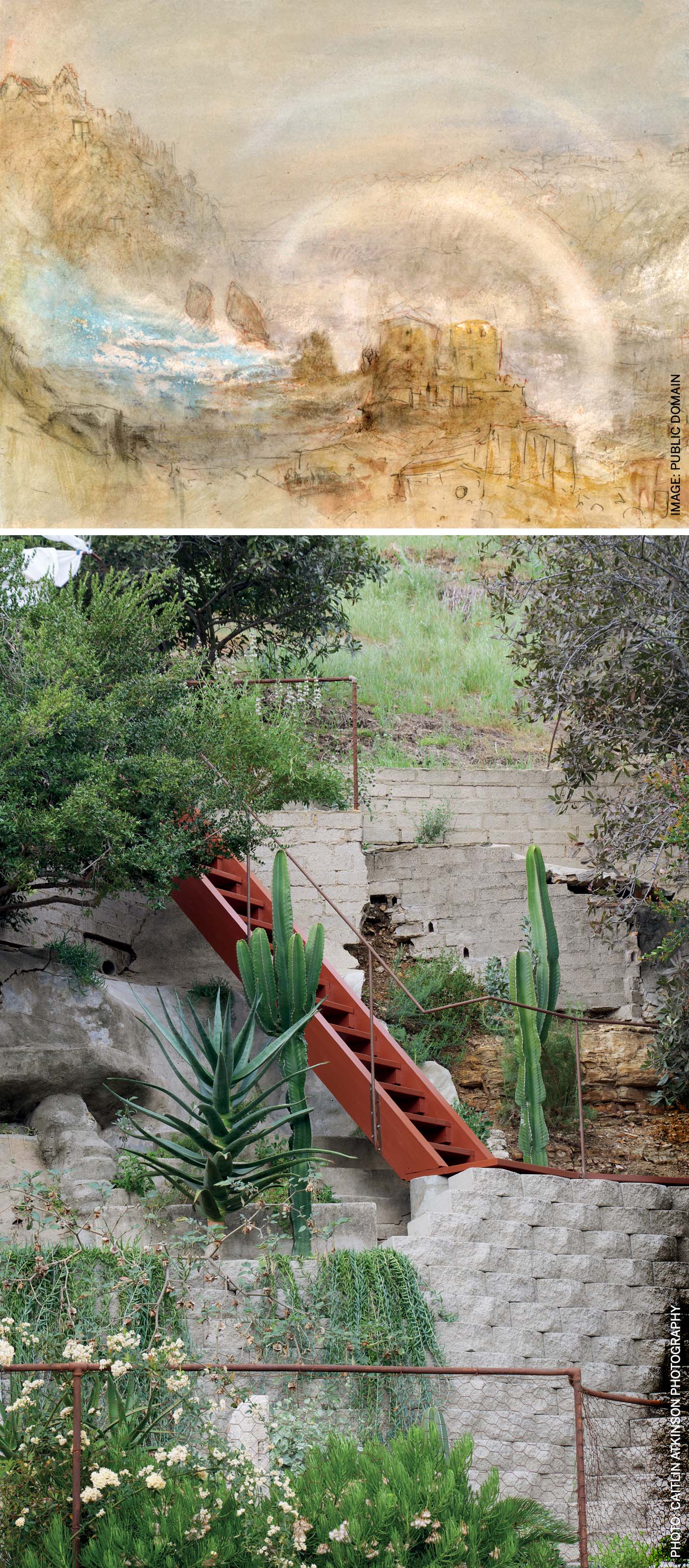

The term picturesque evolved over centuries of use. Today, it’s thrown around as an adjective for quaint scenes. It was originally borrowed from Italian (pittoresco) and French (pittoresque) to describe genre painting. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Picturesque grew into a visual theory that encompassed garden design and architecture in England. With the publication of The Stones of Venice (1851-53), a late entry in the Picturesque discourse, John Ruskin added a moral dimension that’s relevant to sustainable design today. He introduces the concept of ‘changefulness’ to describe variety in design, and ‘savageness’, which we might better understand as roughness, for the contingencies of construction. Achieving the first quality requires open-minded designers; the latter is evidence of liberated craftspeople. Ruskin critiques classicism for rigid idealism in which design

and labour are slaves to perfect abstractions.

The construction process and subsequent wear and tear create distance between a classicist building and its idealised archetype (Palladio famously ‘fixed’ his built work in published drawings). As a counterpoint, Ruskin praises Gothic architecture for aestheticising imperfection. Built over decades according to loose, ever-evolving plans, the Gothic is grounded in how things are made and unmade by time.

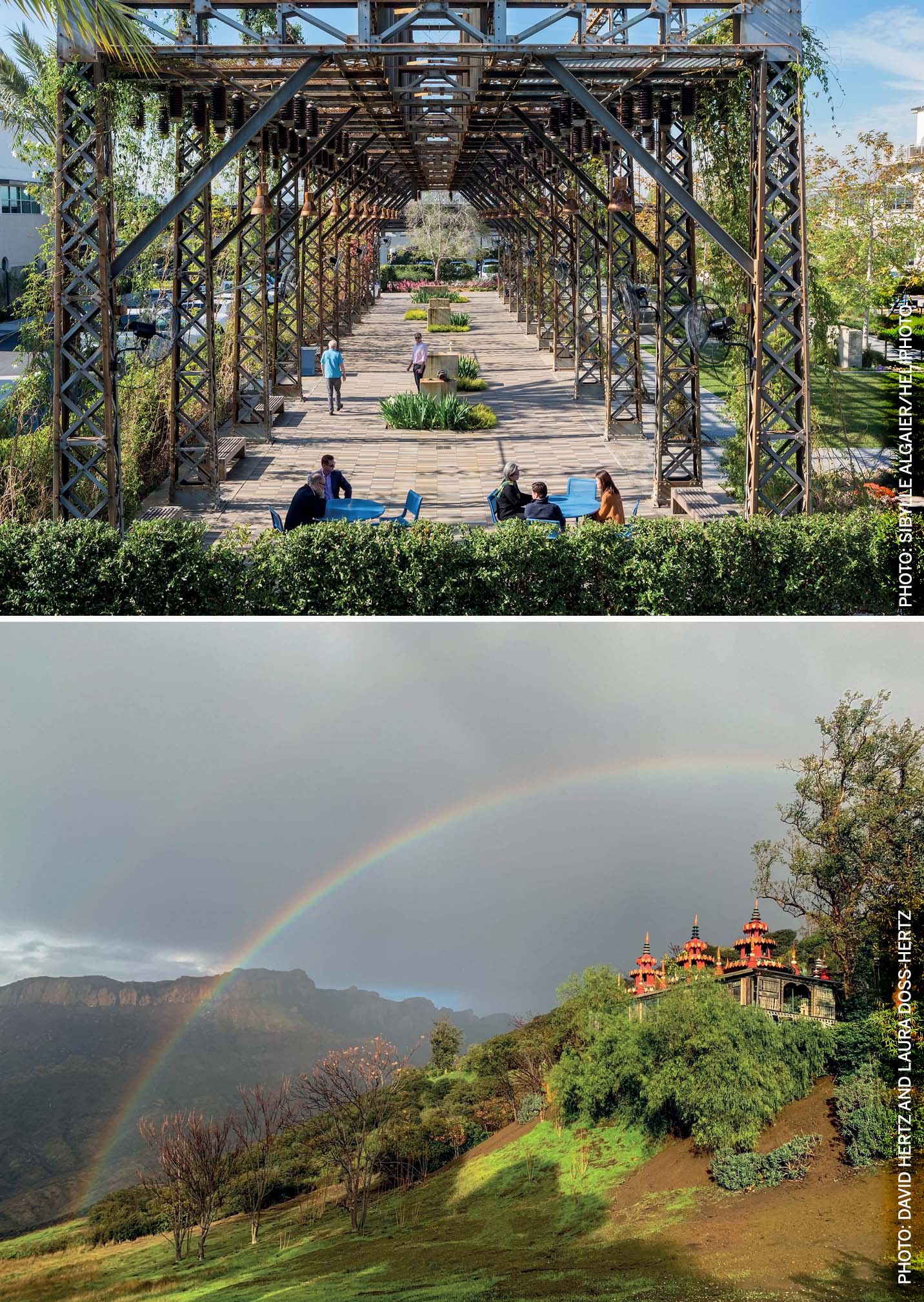

Echoes of Ruskin’s theory resonate in some built environments today, which might collectively be described as the New Picturesque. One example is the Centennial Courtyard in Burbank, California. Once a no-man’s land at a municipal utility yard, the site was reimagined by AHBE as a sustainable landscape. The renovated Burbank Water and Power HQ (rechristened the ‘EcoCampus’) combines all kinds of cutting-edge green strategies, but the standout element is the least functional one: a decommissioned substation converted into a trellis. The gravel bed around it was cultivated into a garden, and the area beneath it cleared and programmed for people. No longer thrumming with electricity, the superstructure stands as a monument of progress towards a sustainable energy economy.

The Centennial Courtyard upends the trope of the machine in the garden. Instead of interrupting nature, the inert substation is subsumed by it. Plants creeping up its rusted columns amplify the obsolete object’s patina. The trellis resembles a Greek ruin, the garden around it an homage to pastoral settings. The courtyard is like an urban excavation site boxed in by adjacent office buildings. The compact relationship between old and new is common in Rome, where unearthed architecture stands in situ amidst the Eternal City. The substation evokes those vestiges of antiquity: the rhythm of steel members recalls a colonnade and the braced rectangles above frame an entablature. Here, Arcadia is not apart from technology.

The problem of new-ness is even more pronounced in green design, which increasingly emphasises high-tech solutions

Another New Picturesque temple is located to the south at The Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Chris Burden’s Urban Light repurposes 202 street lamps from the 1920s and ’30s, connoting a period of dynamic growth in L.A.’s history. The work connects urbanism and architecture by condensing a city grid of street lights into an outdoor hypostyle. The cluster approximates the pitched silhouette of a Greek Temple, but not quite. The roofless colonnade intentionally violates the rigid symmetry of its classical antecedents, reflecting the changefulness espoused by Ruskin. The composition is not symmetrical, nor is each row uniformly populated by the same luminaires. Nonetheless, unity is achieved through tight organisation and a coat of grey paint. Discovering the street lights’ sculptural individuality becomes a game, like looking for details in a Gothic cathedral. Your attention oscillates between the part and the whole, the trees and the forest.

Urban Light is an assemblage, a new thing made from old parts. Tony Duquette, a designer of Hollywood’s Golden Age, was a master of this artform. A true Renaissance man, he repurposed ordinary objects into high and low art, including film sets, costumes, interiors and sculptures. Duquette’s magnum opus, Sortilegium (Latin for divination), was a cinematic landscape strewn across the Santa Monica Mountains.

Bottom: The Triple Pagoda at Xanabu, a Tony Duquette structure restored by David Hertz and Laura Doss-Hertz

His Malibu ranch originally included 21 themed structures across 150 acres of chaparral. Like the follies of an English country garden, the installations displayed Duquette’s refined taste and worldly sensibilities. Whereas a British estate catalogued the spoils of the empire, Sortilegium celebrated global traditions. His longtime creative partner Hutton Wilkinson writes that, “to erect his fantasy houses he collected architectural fragments, Georgian shop fronts from Dublin, Chinese roofs, columns, doors, windows, bathtubs, pavilions, mobile homes, backs of trucks, old windows and much more.” There’s no embedded hierarchy. Duquette delighted in the diversity of design from around the world. Calling it eclectic doesn’t cut it: he was pluralist, practicing an inclusive maximalist style all his own. Duquette’s work has a painterly quality, in which the overall image and the individual brushstrokes are equally meaningful. From afar a piece may look like a Thai pagoda, but up close it is revealed to be a bricolage of paint cans, saucers, satellite dishes and oil drums. By seeing potential in everything, he made junk beautiful.

Like the follies of an English country garden, the installations displayed Duquette’s refined taste and worldly sensibilities

Tragically, the majority of his surreal retreat was destroyed by a wildfire in 1993, yet fragments of Sortilegium survive today. On the same property, architect David Hertz extended that tradition of radical reuse with the 747 Wing House. The residence adapts the wings and tail stabilisers of a Boeing 747 as architectural roofs (Duquette had sourced aerospace surplus on a smaller scale, deploying perforated Marston Mat as a facade material). The upcycled 747 components were exhumed from an airplane graveyard in the nearby High Desert. The apparition of disembodied wings hovering on the land testifies to the temporality of all things.

After working on that project, Hertz and his wife Laura purchased the adjacent land, where most of Duquette’s extant Malibu structures endure. They named the ranch Xanabu, a portmanteau of Malibu and Xanadu, the mythical summer palace immortalised in a Coleridge poem. The property lives up to its namesake. Xanabu is located atop a ridge where mountains fall into the sea, like a scene painted by J.M.W. Turner.

Bottom: Urban Light (2008) by Chris Burden

More than a literary allusion, the name speaks to the development of the New Picturesque as a mode of high-performance design. In 2018, the Woolsey Fire narrowly missed their ranch, galvanising the Hertz family to transform it into a model of adaptation in the wildland-urban interface. The grounds may be idyllic, but Xanabu is scientifically engineered as a defensible space to fight fire next time. The varied topography is calibrated to provide room for emergency vehicles to drive and turn around. A grove of young oaks draws a wonderful line across the land while doubling as a fire break. Permaculture at the top of the property is a local source of food and an attempt at creating a high humidity zone to direct fire away from the primary residence.

The crown jewel of these efforts is a pond, born from the necessity of conducting a well test. Rather than waste the tapped groundwater, the architect diverted it to a tiered basin at the bottom of the ranch’s watershed. Native plants ring the pond like a necklace, changing shape and colour with the seasons. In addition to being a foreground element in the view from Duquette’s Triple Pagoda, the pond serves an important restorative function. The Woolsey Fire burned nearly 100,000 acres of habitat (roughly 88% of federal parkland in the Santa Monica Mountains). As the pond matured, birds as well as frogs and turtles became established there, and even coyotes, bobcats and mountain lions have stopped by the watering hole.

By seeing potential in everything, Duquette made junk beautiful

In the 18th century, the Picturesque was conceived as a mediating aesthetic between the beautiful and the sublime. At Xanabu, this dichotomy finds new expression in sustainability as a balance of regenerative design and resilience planning. Regenerative design proposes buildings that do more good than harm, a utopian aspiration akin to the beautiful; resilience planning facilitates human adaptation to the unyielding forces of nature, aka the sublime. Xanabu unifies these two extremes in one place, one system, one aesthetic.

The Old Picturesque was applied as a practical theory of land improvement in the 1800s, and as a result is inextricably linked with aristocratic gardens. The New Picturesque is decoupled from power and applicable to projects of any size, evident in the landscape architecture of Terremoto. Land improvement implies taking what is and making it better, and founding principal David Godshall refers to their technique as “radically marrying the old and the new on the site.” The studio rejects starting from scratch, and they try to avoid hauling stuff off-site where it becomes someone else’s problem. Terremoto’s designs respond to the uniqueness of every site, artfully amplifying and suppressing existing conditions in a way that’s authentic to each place. This low impact philosophy engenders changefulness by melding a landscape’s past and present.

Bottom: A garden in Mt. Washington by Terremoto

Terremoto champions an economic revolution in land improvement. They wrote a manifesto calling out designer privilege and the lack of labour recognition in the built environment. As designers, they empower the work crew as collaborators in the artistic process. In L.A.’s Mt. Washington neighbourhood, Terremoto and the construction team worked together to refashion a steep backyard into Tibetan steps. The hillside property was a palimpsest of civil engineering, with layers of construction bracing a precarious slope. Accretions of bricks, blocks, pavers and gunite were reconstituted into a series of garden terraces and some artifacts were stacked or repositioned into art objects.

The most inspired moment is when block courses in the wall peel off into stairs. Terremoto didn’t ‘overdraw’ this feature; instead, they approached the contractor and his team with an idea and encouraged them to discover a beautiful solution. This mutual trust hearkens back to Ruskin’s belief in the roughness of Gothic forms. Ruskin argues that imperfections in execution attest to dignity in design: “Men were not intended to work with the accuracy of tools,” he writes, “If you want that precision out of them… you must unhumanize them. All the energy of their spirits must be given to make cogs and compasses of themselves.” Terremoto’s work is precise, but it possesses a roughness that speaks to the reciprocity of craft between designer and builder.

Ruskin argues that imperfections in execution attest to dignity in design

Their volunteer project in Elysian Park is a parable of paradise lost and regained. Named for the Hellenic afterlife, the park is a dystopia of civic neglect and invasive species in L.A. The city deemed the land unsuitable for development and dedicated it as a public amenity in 1886. The deforested Elysian Park was subjected to a beautification campaign between then and 1892 in which 150,000 trees (Australian eucalyptus and other foreign species) were planted. This artificial wilderness has grown out of control for the last century, representing the failures of the Old Picturesque to impose human notions of nature onto the land.

The Test Plot is Terremoto’s attempt to return harmony to Elysian Park’s biome. The endeavour consists of radial native gardens located around the park, each exhibiting its own changefulness in response to the specificity of site. The picket fence surrounding each garden is a cheeky reference to pristine suburban lawns. The Test Plot is a collaborative effort with community groups that’s maintained by volunteers. Future Test Plots are planned for other parts of the park, perhaps they will one day overwhelm it. This movement of guerilla gardening marries activism with ecology, a unified aesthetic of social and environmental sustainability. In these garden beds, the seed for the New Picturesque has been planted amidst the ruins of the Old — spots of light across a stormy Turnerian sea.

So far, the best examples of the New Picturesque involve landscape architecture, a field that doesn’t have other disciplines’ bias for new-ness. People who design and tend landscapes naturally embrace changefulness and roughness because they work with living media. Gardens aren’t ready on Day 1, they grow in place in surprising and unforeseeable ways. Sustainable design of all kinds would benefit from this ethos. In Walden, Henry David Thoreau writes that, “There is nothing inorganic.” When we accept that the machine has always been part of the garden, we will finally create places that look sustainable and are sustainable.

Comments (0)