The Covid-19 pandemic has brought human fragility and mortality to our psychological forefront. It has highlighted the most fundamental aspect of our existence: our health. It has redirected our attention to the relationship between our collective and individual well-being and the built environments in which we live.

We are not strangers to epidemics and pandemics. The Black Death killed millions in the 14th century. Increasing transportation in the late 1800s spread influenza across the globe. The Swine Flu killed more than 500,000 people in 2009. From 2015-2016, the Zika virus spread from Brazil to parts of South and North America and South-East Asia. Epidemics and pandemics have ravaged humanity before. But they have also offered profound insights on the connections between our habitats and what we call disease, and instigated strategies to enable us to endure health crises.

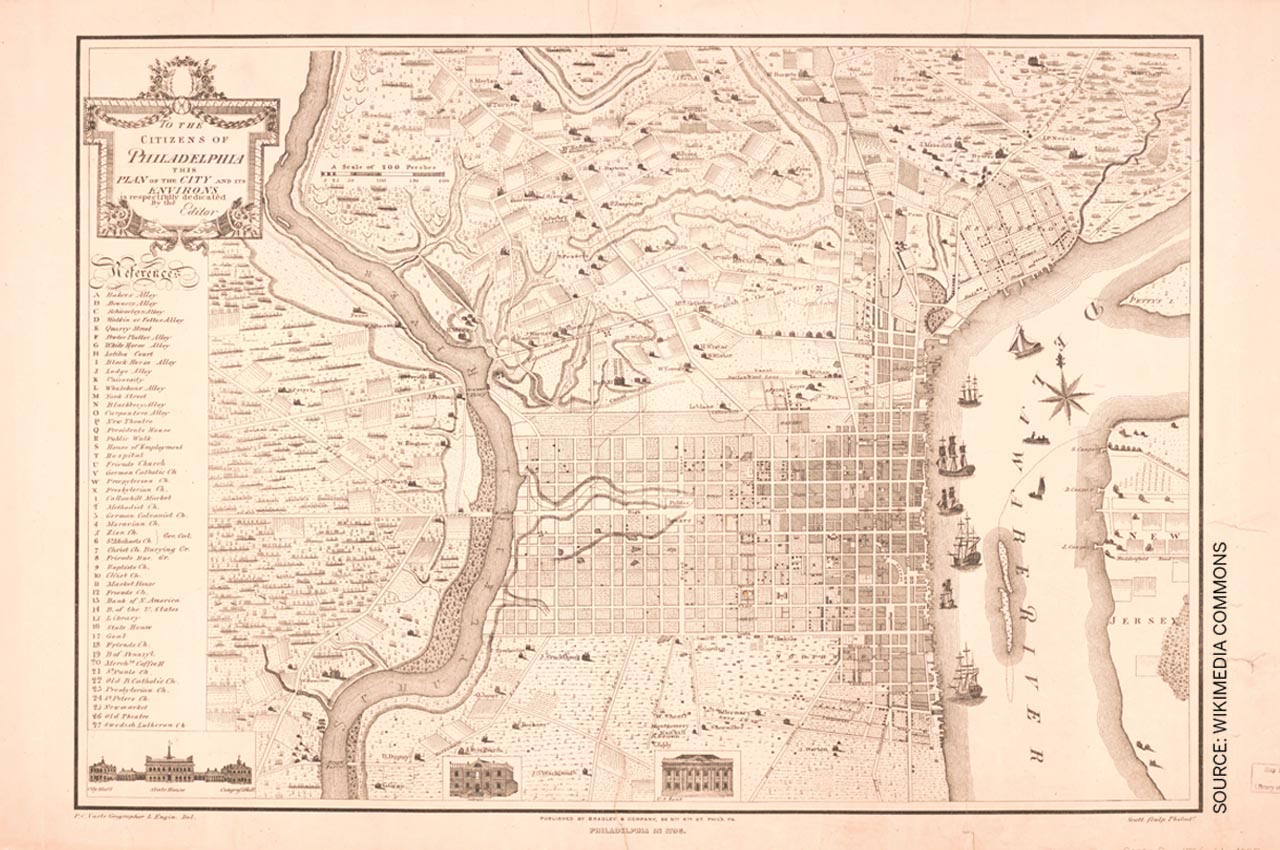

For example, William Penn, the founder of Philadelphia, one of the first great planned cities in the United States, had survived the plague and the Great Fire of London in the 1660s.

The cholera outbreak in London prompted the 1848 Public Health Act with the establishment of the general Board of Health. Subsequently, social reformer Edwin Chadwick who became an officer of the London Metropolitan Sewers Commission ordered all cesspools and sewage pits to be cleared from the streets and dumped into the Thames, the inevitable result of which was the Great Stink of 1858. And this in turn led to Joseph Bazalgette’s 1877 engineering solution of channeling the waste through miles of street sewers into intercepting sewers to be transported downstream into the tidal water of the Thames and swept out to sea.

Concerned that tenuous non-rectilinear street patterns were susceptible to stagnating water, he planned the new city in 1682 as a rectangular grid of streets headed toward the Delaware River. Each house was placed in the middle of a large lot surrounded by open space on all sides, and each quadrant featured a public square to prevent overcrowding and allow ample sunlight and cross ventilation.

When yellow fever infected its residents in 1878, the city of Memphis, Tennessee, undertook a detailed citywide lot-by-lot survey prepared by a diverse team of experts. Engineers inspected buildings for new code requirements. Doctors helped identify places that could be susceptible to disease and planners sought strategies to decongest overcrowded neighbourhoods by designing parks and green spaces. The epidemic had forced the city to recognise the need for a significant public health strategy through multidisciplinary collaboration to prevent another health crisis.

In the mid to late 1800s, increasing density and population in the early industrial city instilled the fear of catching disease via foul air, and buildings and outdoor areas with fresh air and sunlight became a priority.

For example, Manhattan’s grid was originally designed in 1811 with no parks and it was not until the late 1840s, when the American city was growing due to industrialisation and immigration, that leaders began to call for green space.

The result was the nation’s first great urban park, Central Park, conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted and built in 1858 as the ‘Lungs of the City’. The creation of parklands was so intimately intertwined with public health that Olmsted left his post as superintendent of Central Park to become general secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission, which would become the nation’s largest national public health effort.

With increasing industrialisation, the physical separation of noxious uses like slaughterhouses and steel plants from places where people resided overlapped with important medical discoveries that had a direct impact on city making. For instance, in 1897, British doctor Ronald Ross’s discovery of the malaria parasite in the gastrointestinal tract of a mosquito had a significant impact on urban design and planning. In colonial India, circa 1931, the city of New Delhi was built to be physically disconnected from the older labyrinthine 17th-century walled city of Shahjahanabad. A hygienic zone in the form of a vast open space separated the two, and its width was carefully calculated per the maximum flight distance of the malaria-spreading Anopheles mosquito.

Meanwhile, sanitarians started filling up urban tanks and village reservoirs in colonial India to prevent mosquito breeding — a trend that was criticised by British town planner Patrick Geddes. The cooling effect that the reservoirs had on their habitat surroundings and the cultural significance of these waterbodies to the socio-religious life of the indigenous people had not escaped him. He argued for more ecologically sensitive approaches such as “clean(ing) them thoroughly and then stock(ing) them with sufficient fish and ducks to keep down the Anopheles” while also noting that the “cleansing of tanks costs but a fraction of the cost of filling them.”

Geddes’s wisdom, stemming in part from his training as a biologist, was far ahead of its times. He was reinforcing how the fields of city planning and public health were not only interrelated but also intertwined with other environmental, social and technical sciences, all working hand-in- hand toward a holistic vision for a healthy city.

But with the over-bureaucratisation of municipal governments and the increased specialisation of engineering fields, multiple disciplines with broader overlapping goals became increasingly autonomous and less communicative and the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed gaps in this system. Today, our ongoing urban development patterns are directly detrimental to our health. Urban policies and zoning codes, over recent decades, have enabled entire communities that have no access to healthy food, rely on the car and discourage people to walk, leading to increasing obesity, asthma and heart disease. Homes, schools and even day-care centres are built adjacent to toxic freeways and major arterials, contributing to the growing list of our health problems. The global syndrome of overburdened hospitals, lack of infrastructural upgrade, increasing pressure on healthcare professionals and the absence of healthcare for the underprivileged is also an extension of this discipline separation. And even in the most developed societies of the world, all this occurs legally, through policy and regulation.

while also serving as a community space

Like before, the pandemic is now prompting serious questions about our cities from a health perspective: Will social distancing generate a more polycentric urban landscape with our daily needs within walking distance of our homes? Will it incentivise the creation of more open public spaces? Will it encourage our dwellings to be naturally ventilated and discourage air-tight buildings? Simultaneously, the pandemic is raising concerns: Will returning to the inner city — an increasing trend over the past two decades — wane as people seek more pastoral places to reside? How will the informal sector and its unplanned habitats, which form such a dominant portion of developing societies, cope with this crisis? Numerous questions are already part of significant dialogue as we come to terms with what this pandemic means for our immediate and long-term future.

As we contemplate such questions, we must not fail to notice the pandemic’s numerous silver linings. During the lockdown, we have been forced to rely less on our cars and many of us have created new exercise routines while working remotely in our houses and neighbourhoods. People living in closed buildings are spending more time outdoors. Awareness of personal and public hygiene has seen a surge, particularly with health authorities advocating for regular handwashing, and there is a good chance this will not wear off easily. In the post-Covid-19 city we will expect our municipal leaders and health departments to be better prepared and far more invested in disease preparedness and response. And so, it may be that our digital interactions for business and work, renewed sense of personal and communal health, and calculated frugality in daily habits are not only an effective but also an environmentally friendly way to live after the pandemic has passed.

In as much as this pandemic has startled us all, it has also made us realise that our pre- Covid-19 urban patterns were neither good for our health, nor that of our planet — and the two are inextricably interrelated.

After a long time, the air we breathe in our cities is cleaner, our forests and oceans are less disturbed than they were in decades and we are conscious and attentive to what this means for our health. We are beginning to realise that our cities are not just engines for commerce and social life. They are also the conduits and settings for our collective and individual wellness.

The term ‘wellness’ is important here. While health may refer to the absence of disease, it does not always encompass emotional well- being or mental stress. It does not necessarily include the toxins in one’s body due to an unhealthy diet or lifestyle that have long-term consequences. The fact is that what we call ‘health’ is not the end goal as much as the first step toward wellness — taking one’s health to the highest potential by changing daily habits and being accountable for them.

How our cities are made and sustained are an intrinsic part of this and we must therefore recast the processes and products of shaping them toward this goal. The most significant shift we can therefore hope for in the (post)- Covid-19 world is to return city planning, urban design and architecture beyond their aesthetic and technical dimensions to their higher and more consequential purpose: a health- project aimed at rejuvenating both human and environmental wellness at all scales.

This essay is part of the author’s forthcoming book titled Urbanism Beyond 2020: Reflections During the COVID-19 Pandemic

(published by MyLiveableCity & ORO Editions, Spring 2021)

Comments (0)