‘Ecological Urbanism’ is a postmodernist idea that researchers fondly indulge in. One uses the word ‘postmodernist’ since the term gives rise to multiple interpretations and all interpretations are contingent on the point of view from which they are being made. Like many postmodernist debates, the discourse on Ecological Urbanism could turn out to be ironic, sceptical and based on fragmentary interpretations and not just one truth. With this caution, this article explores the usefulness and contentions around the idea.

There is no denying that the term is well intentioned as it reflects the human concern of the effect of mass scale urbanisation on natural ecosystems. This, coupled with the concern that we need to devise ways to understand and integrate ecosystems in today’s cities, is a relevant and supportive conception. However, the weight behind the term is enormous since both ‘Urban’ and ‘Ecology’ transform each other continuously. It is difficult to find any stable ground for the two. The term ‘Ecological Urbanism’ (EU) requires an expansive scientific, physical and sociological research of ‘Urban ecological systems and co-dependents’. It requires this research to then be applied, enhanced and incorporated into urban living. This is an unprecedented task that needs support from various urban and non-urban agencies. It needs an alignment of interests and a greater vision in an urban citizen’s consciousness or else the term has the risk of getting reduced to a catchy phrase.

Ecological Urbanism and the Anthropocene

In 2000, ecologist Eugene Stoermer and chemist Paul Crutzen coined the term Anthropocene to describe the effects of human activity on the earth’s climate and ecosystems. Scientists claim that this is now visible on the earth’s strata. In fact, some scientists believe that the beginnings of this era started with the Industrial Revolution of the1800s while others claim that the testing of the first atomic bomb in 1945 initiated the Anthropocene. The latter is also known as the time of the great acceleration. The last 70 plus years of human activity have led to the depletion of the ozone layer, ocean acidification, carbon emissions and vast depletion of natural resources. All these activities can be traced to urban lifestyle, urban consumption and urbanisation processes.

‘Ecological Urbanism’ (EU) accepts the present time as the Anthropocene epoch and marches ahead. It shoulders the serious responsibility that humanity has unknowingly taken by modifying the natural systems of planet earth, a gigantic experiment on earth as John McNeill pointed out in his book Something New Under the Sun. Many scholars argue that we are doomed because of our meddling with the earth’s systems and many debate whether human ingenuity will resolve these crises.

Ecological Urbanism is based on two acknowledgements. First that urban is the new way of living for humanity and second that incorporating and enhancing ecological systems with the urban can solve the problems arising from it. Ecological Urbanism looks towards human ingenuity to achieve the best of both: urban living and robust ecological systems. This may appear to be wishful thinking but humans have a limited choice and this could be a step towards understanding what shifts we have to propel to fix the devastation caused.

Natural and Man-made Systems

Natural ecosystems evolve over a long period of time and have a complex web of life supporting innumerable organisms. Human habitation too supports a different scale of ecology that has adaptation and modifications.

Ecological Urbanism is about promoting human habitat where human supportive ecosystems can thrive. This definition poses stark limitations as, in reality, urban processes have many layers of complexities. Ecosystems get formed and destroyed as the urban processes take hold. Urban is formed for human consumption, and making urban centres ecologically thriving systems would involve a radical shift in the discourse around the term ‘urban’. Ecology requires resilience and an attitude of stillness whereas urban is about change and transformations.

Let us examine the city of Delhi and its undergoing transformation to tackle the pressures of urbanisation. Delhi has a history dating back to the 10th Century. Since then, it has been destroyed and re-established eight times. Initiatives and policies of different administrations have given the city different urban forms.

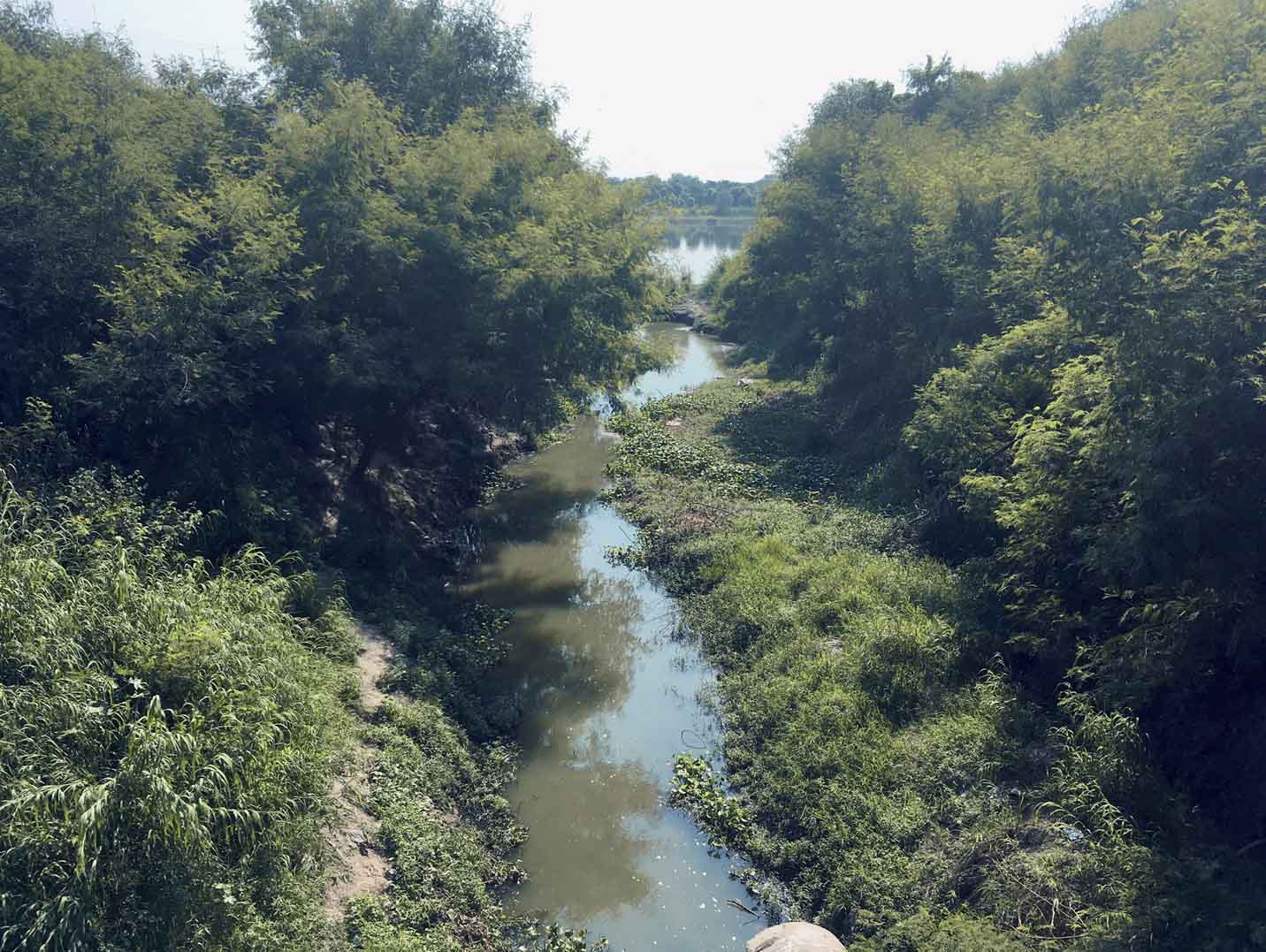

To understand the present process of rapid urbanisation of Delhi and its ecological implications one can look at the fringes of Delhi that are rural and agricultural. The Delhi Development Authority (DDA) has introduced a new land pooling policy to allow more housing to be built along its fringes. The land is notified as urbanisable, though, at present, most of it is agricultural. This process of urbanisation has human innovation and ingenuity at its core but is inadequate in protecting existing ecology. There are water bodies, nullahs (riverbeds), wells and thriving networks of village life that will be destroyed since most of these ecosystems are not acknowledged and documented. A study conducted by the Physical Planning Department, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, on Land Pooling Policy noted that “no mention of existing natural features such as catchment areas” has been made and “climate, hydrology, geology, landforms, soil and vegetation study should be undertaken,” before accepting development proposals. Even when researchers point to the merits in acknowledging natural systems and protecting such systems, city development processes are too hasty to heed these cautions.

‘Urban’ and ‘Ecology’ transform each other continuously

The other example is of massive re-development that is reshaping Delhi. After Independence, the Central Power Works Department (CPWD) had laid down several residential colonies that housed Government office staff. Housing colonies such as R. K. Puram, Sarojini Nagar on the inner ring road were built in the 1970s. These are mostly ground plus one floor high; some go up to a height of three floors. They have type 1 to type 8 dwelling units of area 41 to 425 sq. m. respectively. With ongoing redevelopment, the city is now embracing a new urban typology that is high rise: ground plus eight floors high. Citizens have expressed their concern over this transformation for densification and upgradation of old housing stock. Over a span of 40 to 50 years, residents have nurtured these areas by planting trees and growing gardens. With new urban typology, newer ecosystems will thrive albeit after a long time. All this at the cost of destroying already existing ecological systems that are supported by social groups and communities. The process of redevelopment in Delhi does not acknowledge what is already good at site. As a result, Delhi’s environment continues to deteriorate at an alarming rate.

According to ecologists, Delhi lost its common sparrows because of wi-fi towers and loss of their habitat due to changing urban form. On 19th March 2018, national newspapers reported that in Delhi, the new generation of smallest vertebrate, the small common yellow frog was showing physical deformity such as absence of eyes at birth due to water pollution.

In urban areas, ecosystems thrive in unplanned, contested, leftover and neglected areas as well.Robust species of plants and dependent organisms such as insects, lizards, mongoose and snakes thrive in these smaller ecosystems. The Environment Impact Assessment reports for redevelopment sites do not acknowledge these ecosystems. City ambitions, instead of conflicting with ecology need to realign with it as this alignment can pave the way to be truly ecologically urban.

Conceptually there are three contentions around the term ‘Ecological Urbanism’. These contentions arise from our past practices, our value system and practical issues of distribution and condensation of resources.

Contention 1: New Idea or Age Old Wisdom?

Is the term ‘Ecological Urbanism’ truly a new idea? Have we not, before, lived in urban centres without incorporating the ecological systems?

Every time Delhi was re-established, it was primarily laid according to the defence strategy of that time and the availability of water either by the river or by systems of ponds and wells. The city was small and most natural ecosystems lay outside the city. Yet the understanding of ecology is undisputable. Right from healing baolis (stepwells), fruit orchards to baghs (gardens) of fragrance and floral beauty along natural streams and canals, they all supported royal functions. The present-day vestiges of these erstwhile urban centres convey the ecological sensibilities of those times.

Cities have thrived when they incorporated ecological rhythms that supported city functions. Today, the city is bigger, complex and rapidly evolving, yet it survives well when it integrates harmoniously with other ecosystems.

Ecological Urbanism is about promoting human habitat where human supportive ecosystems can thrive

Contention 2: Urban as compact and nature as sprawl

The second contention is that if we were to integrate ecological systems in urban areas as rigorously as we urbanise our habitats, will we be able to retain our urbanity? This contention springs from the urban-rural binary. Theoretically, there is a tendency to see rural as more ecologically relevant than the urban. For a long time, one associated with this binary until the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, during which the scale of urban habitation multiplied and posed new challenges. The Garden City was a methodical attempt to introduce an urban model with the best qualities of urban and rural. It also reflected the recognition of deficiency of nature in the city, and an attempt was made to look towards rural habitat to seek solutions for this. Broadacre City was another possibility of seeing this reconciliation. These models, though well-intentioned, produced sprawl and compounded issues of mobility and pollution.

In Delhi, the influence of such models can be seen in the picturesque English landscape of Lodi Gardens and parks of many sizes in residential enclaves and large farmhouses on Delhi’s periphery as suburban living for the wealthy. Lutyen’s New Delhi, with boulevards laid on axial geometry with jamun and Ficus trees lining them, is considered sprawl and too lavish. However, monkeys, cats, dogs, birds and insects have created their abode around these mature, majestic trees. This urban sprawl is sometimes referred to as the green lungs of the city. Urban areas often deal with contradictions that do not have a clearcut solution.

All urban centres through history have embraced different scales of ecosystems. Though all of this has been the result of logic and convenience of the time, these parts have given a distinct urban character and variety of form to urban areas. Cities that are facing pressures of urbanisation such as Delhi have a tussle between ‘thriving ecosystems’ and ‘compacting city’. A bid to balance the two is often detrimental to one or both. It becomes a conflict between the urban and nature.

Contention 3: Urban value system

The third contention is that ecological urbanism needs a process of accepting and protecting existing ecosystems along with the introduction, nurturing and growth of new ones. In this process, our attitude towards other species and nature become crucial. Ecological Urbanism can become relevant by drawing inspiration from Aldo Leopold’s vision of a land ethic where human beings have obligations that are above self-interest. This can be achieved when human habits and lifestyle are ecologically conscious and strong enough to make decisions that overcome our desires to protect other species and ecosystems.

In order to be truly ecologically urban, a value system is needed that is based on compassion and generosity; not on an individual’s efforts but as a conscious social endeavour.

Comments (0)