When we think of art in the context of the city, we immediately think of aesthetic or artistic products. But another aspect of this nexus is the way in which art becomes woven into the process of city-making. Are your work and initiatives an embodiment of this idea – art as a process of making; art as a verb, not a noun?

Urban planners and artists occupy the same space. Most planners, however, think about cities in head-heavy ways and use abstract tools like maps, data and policy to understand, explore, control and regulate the land. They do not let the land speak for itself. Artists, on the other hand, begin their inquiry through a sensory experience, which is how people experience the city.

For the public, the city’s physical environment is a spatial, visual and emotional language formed by memories, needs and aspirations. Its building blocks comprise more than simply structures, streets and sidewalks, but equally encompass personal experience, collective memory and aspirations. These elements, while less-tangible, but no-less-integral, transform mere infrastructure into a place that can be best captured through art-making.

Rather than ask people what they want or need in their community as in most planning meetings, residents build solutions with objects, based on their own on-the-ground knowledge and imagination. When people are busy creating they don’t have the time to argue or complain. Through material expressions of ideas and imagination made by residents and/ or users themselves, this method improves communication, inquiry, reflection, collaboration and ownership of the process and idea generation in a quick and playful manner. Planners can capture this information to establish collective values as a metric to measure development of urban plans or policies and promote further discussion, projects, plans and policies.

I appreciate the beauty in a piece of art; however, it’s the production of it that intrigues me as well as the sensory experience of the place it uncovers. Therefore, art-making is an integral part of my city-making process called Place It!

The city’s physical environment is a spatial, visual and emotional language formed by memories, needs and aspirations

Can you summarise the working and process of Place It!

Place It! is for visual and spatial thinkers, youth, women, non-native English speakers and users of the right side of the brain. Through trial and error, Place It! has developed a formula through four activities that use prompts, storytelling, the body, landscape and objects. Each activity responds to various conditions, venues and goals.

The Place It! workshop begins with a reflective prompt. Participants are asked to build their favourite childhood memory in 10 minutes choosing from hundreds of small, everyday objects like corks, plastic eggs, blocks and hair curlers, markers, etc. The childhood memory prompt serves as an icebreaker, reconnects participants to their core human values and is the closest feeling people get to utopia. It changes the mood of the participants and they generally create sharing and nurturing places. After the time is up, everyone shares their memory with the group in order to learn from one another, validate their lived experiences and build empathy.

Once this initial task is completed, participants are placed in teams and asked to ‘Build their ideal community’ (or a similar prompt depending on the specific goals of the workshop) in 15 minutes using the same objects. The teams are given no constraints so they can choose their own issue and solve it. Once each team has completed their community models, they present them to the group.

After each team presents their solutions through the model, each team member is then asked to pick a specific day and time and describe an activity that would take place in their model. This final step truly gives the model a life of its own and brings out the participant’s deep knowledge of how spaces work and how urban planning should reflect their values. As a wrap up, common values are uncovered along with short- and long-term solutions.

Pop-Up Interactive Models are not static pieces of art, but interactive tools to unleash people’s visceral urban knowledge and communicate it in a new and meaningful way. These models capture the power of the collective community’s imagination through engaging with a landscape and objects in public venues and spaces. Residents, tourists, visitors and the public can reflect on, explore, experiment and ultimately craft their ideal community by moving objects on the map. These models highlight geography, streets and landmarks. They are usually constructed from foam boards and construction paper and are designed to fit on top of a standard 6 foot by 30 inches platform; it is lightweight so it can be moved to various locations for easy installation.

Small buildings and objects are provided with the model. During the public interface, the model serves as a hands-on, 3-D tool for the participants to share their memories, needs and aspirations for their community. People are able to place them anywhere they choose to. Therefore, the public engages in the three-dimensional model by reading it like a map and by touching and modifying it. By touching and moving the small buildings on the model, the public is allowed to investigate various urban forms that typify the city and project their own ideas onto the model about the physical nature of the community. In this way, the viewer becomes an active participant in the creation and evolution of the city planning process. Through this process one is able to understand how this city is physically created, experienced and imagined.

Sensory-based site investigation allows for individuals to use their sensory experiences and imagination to re-envision spaces and ultimately contribute to more responsive and accessible land uses and design. For the first step people tour the site. Parking lots work well. They have ten minutes to explore the site and choose a location they find comfortable. Once they zero in on their spot, the group reconvenes and visits the chosen individual sites. The participants present their site to the group and explain why they chose it. These narratives are interesting because no two locations and experiences are ever the same. Through this activity participants learn how their bodies relate to the built environment; it also illustrates how human nature looks for comfort in the built environment and serves as an ice breaker for the group. This activity is followed by a workshop.

Interpretive Walks help people examine, explore and create a physical and mental desire to connect with one another and the intimate details of the landscape through the body and memories. Residents and stakeholders walk together and talk about their memories and experiences of a place. These intimate details, like the pages of a book, help us understand this community. These walks capture the community’s pulse and reinforce the social bonds of community. Participants are both the viewers and the observed. The walks help people articulate their sensory needs.

In summary, Place It! sensory activities are created for people to examine and landscape through a different urban planning lens. People learn how to articulate their needs, ask better questions on the design proposals and projects and ultimately find common ground through landscape, memory, experiences and aspirations.

Tell us about some of your projects and initiatives and their successes and shortcomings.

There were about 75 low-income Latino residents at an Eastside transportation meeting. I was working for LA Metro and the agency was planning the $900 million rail project through their community. These residents had the lowest auto ownership, highest transit use in LA County, and they had more on-the-ground knowledge of using public transit than most of the transportation planners. Yet these residents made very few comments at the public meeting. That’s when I realised community meetings were not engaging diverse audiences, thinkers and personalities. At the same time I opened an art gallery in Downtown LA and was able to experiment and develop Place It!

For the past 10 years, through word of mouth, I have facilitated over one thousand Place It! workshops and trained hundreds more to use this approach. I have installed hundreds of interactive model pop-ups from Tijuana’s Colinas to Bronx’s Laundromats. I collaborated with grassroots organisations, artists and others who seek to engage mainly under-represented communities, which include youth, people of varying ethnicity, immigrants, women, elders and the LGBTQ community.

In 2013, I collaborated with Phoenix’s disabled community to help improve access to their newly built state-of-the-art Ability 360 Center. Dozens of people, all with disabilities, participated in the workshop to envision their potential station. This workshop helped them articulate their voice and turn their struggle into a station design. As a result of the workshop the group was so motivated it lobbied local government to build the station. In 2018 the city opened the new 50th Street station to serve this community.

The public engages in the three- dimensional model by reading it like a map and by touching and modifying it

The Compton elders shared high-fives after they presented their ‘Heritage Park’ vision for the Artesia Light Rail Station Area. This activity was jubilant for these African- American women, because for the first time they could build their love and knowledge for their community with objects into a three-dimensional model for their ideal station area. Place It! helped them plan this station that would reflect their history and emotion.

South Colton’s recently approved active transportation design guidelines folded Place It! with Latino Urbanism. Our creative, hands-on and culturally informed community engagement events ultimately led to an uncovering of real, on-the-ground local knowledge and expertise that embraced how many Latinos use public and private space.

Place It! helps to reframe the planning issue but, more importantly, to uncover the sensory experiences of place that maps, data and other typical planning tools miss.

How can art in multiple forms enhance community involvement in the planning process? How can it enhance or transform mainstream planning?

Art-making is a powerful tool to foster social and racial equity through civic engagement because it breaks down barriers such as language, age, ethnicity and professional training. People are happy when they create, rather than just talk.

Art-making raises people’s consciousness of built environment elements:

- Social Cohesion: Reinforce their bounds and concern for families, friends and neighbours.

- Belonging: Discover how they belong physically and socially to one another and the community.

- Healing: Understand their struggle and heal each other and the environment.

- Aspirations: Highlight their aspirations and set their own goals.

- Self-determination: Encouraging people to plan for their own future and act on it.

- Collaboration: Let people realise that when we bring diverse backgrounds, experiences and perspectives together we are strong.

Art-making also removes economic and political barriers to help people find commonality through their core human values. This bridges the gap between mainstream planning and under- represented communities because it increases the safe space for everyone to come together, listen, share, bond and collaborate to find common memories, experiences, aspirations and generate cutting-edge ideas and solutions for their communities.

Rather than use maps and numbers, which oftentimes merely repackage and transfer knowledge amongst people, through art-making people create new planning knowledge that they did not know they had. Directly involving participants (as opposed to ‘audiences’ or passive viewers) in re-imagining equitable growth and development in their community it gives them the know-how they need to achieve their goals. Art-making is transformative because people realise they are their own experts.

Art-making is transformative because people realise they are their own experts

You are a strong advocate of informal urbanism, specifically related to the Latino culture in the US. What are some of the main takeaways from your observations on this urbanism, particularly along the theme of art and the city?

Beginning with my 1991 MIT thesis, ‘The Enacted Environment: The Creation of Place by Mexicans and Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles’, I have been researching, documenting and experiencing the transformation of Southern California’s suburban communities by Latinos.

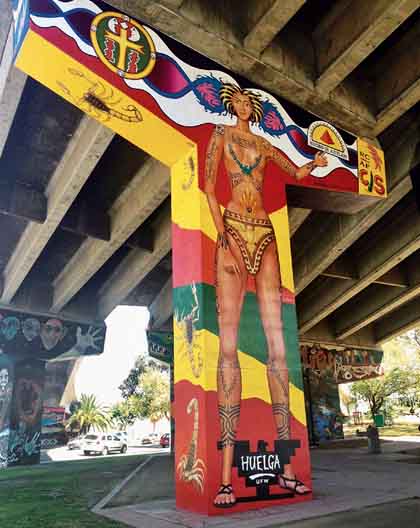

Because many Latinos come to the US with very few resources, they must rely on their basic art-making instincts to fulfill their economic, social and cultural needs. Day labourers and street vendors use streets for work, while Latino homeowners transform their front yards into plazas. Latinas use their front yards for self-expression and cultural preservation. Murals educate and celebrate the power and struggle of the community.

Unlike a conventional American urban or suburban landscape in which order, perfection and a display of values are the ideal, the Latino- American landscape is one of cultural, social and economic production. Every resident has a hand in the production of space and community, which empowers them. These landscapes are culturally vital spaces and culturally informed approaches to the creation of space.

These do-it-yourself adaptations and aspirational interventions create a hybrid style that I term ‘Latino urbanism’. Typically, these urban design interventions have been created in the shadows of municipal codes because the underlying values that created these codes have not been updated or, in many cases, these interventions have gone unnoticed. What is not codified through zoning is remembered through art-making in Latino communities.

The New Urbanism of the late 1980s rediscovered the grand Spanish plans to colonise the new world through spatial order, formalised through the Law of Indies’ planning codes that created thousands of Latin-American settlements. When I was documenting the Latino transformation of Los Angeles County, my MIT colleague was documenting New Urbanist design guidelines. In conclusion, they both produced the same spatial benefits of walkable communities. However, Latinos produced these elements themselves as a cultural expression as in the case of South Colton.

Art-making helps preserve and enhance the Latino community’s values through the Do-It- Yourself urban planning process because it offers new methods of planning inquiry. It also taps into people’s aspirations of place and allows Latinos to add visual and spatial values to suburbia.

Comments (0)