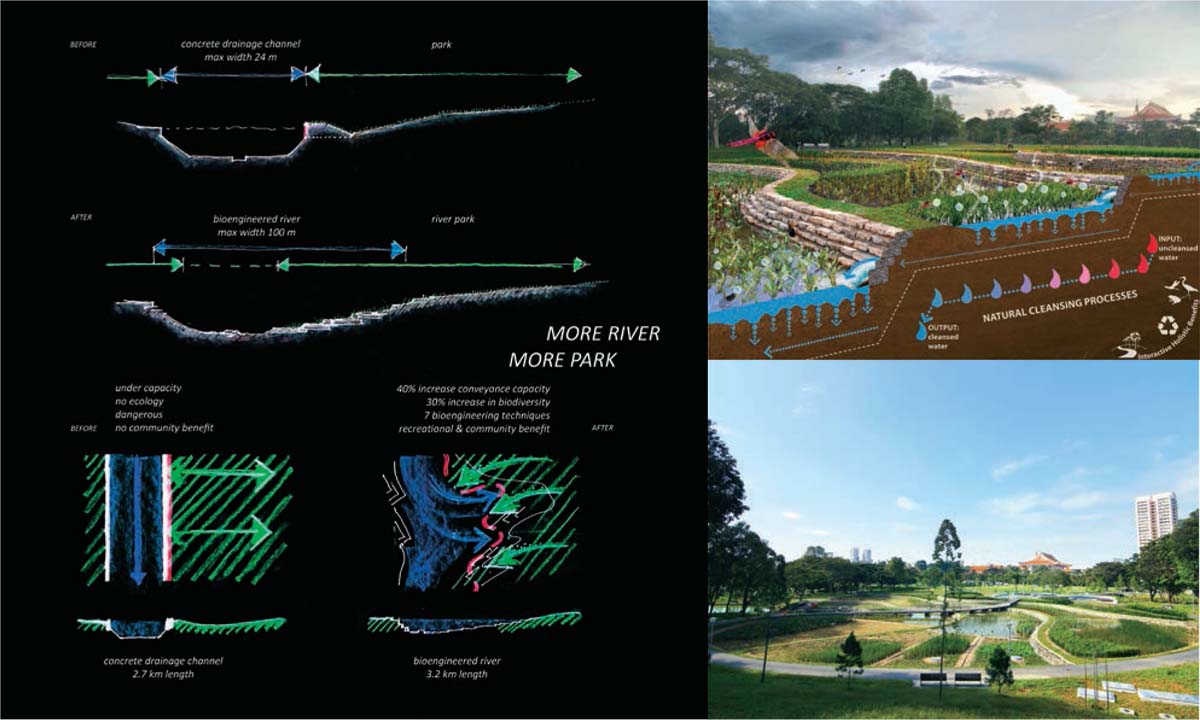

The Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park is a flagship project under the ABC (Active, Beautiful, Clean) Waters Programme. Rather than separate components, the idea of water and its surrounding area is thought of as a whole, where recreation and community bonding occur amidst the water conveyance system. Instead of a physical boundary (as the canal has been in the past), the redesign of the river unifies the park with the neighbouring housing estates to form a whole.

The highlight of this project is the revitalization of the river. The changing waterscape creates multiple uses of land in the park. When the water level in the river is low, users can get closer to the water and enjoy recreational activities along the riverbank. During heavy rain, the river doubles up as a conveyance channel, carrying the flow downstream.

With landscaped banks and gentle slopes, the mild, meandering river provides opportunities for the public to get close to the water and experience its natural rhythm and beauty. This influences the community’s perception and sense of stewardship towards the environment.

THE SINGAPORE WATER STORY

Singapore is an island city-state with no natural aquifers or abundance of land. Although the island is blessed with generous tropical rainfall of approximately 2400 mm a year (compared to London’s 600 mm), there is limited land to collect and store rainwater. Expansive development and a significant increase in its population in the 1960s meant that in the early days the city also faced drought, flooding and water pollution. Many of the natural rivers, including Kallang River, which runs through Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, were made into concrete canals, to alleviate widespread flooding.

Singapore has since turned this weakness into its strength. Through integrated water management, Singapore’s national water agency, Public Utilities Board (PUB), has ensured a robust and sustainable supply of water for its people. Singapore is today a model city for water management and an emerging global hydro hub.

The city has also seen the integrated management of its water resources as an opportunity to encourage the community to take joint ownership of Singapore’s water resources and create a vibrant ‘City of Gardens and Water’.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

The ABC Waters Programme was launched to transform the country’s water bodies beyond their functions of drainage and water supply into beautiful and clean streams, rivers and lakes with new spaces for community bonding and recreation. Simultaneously, it promotes the application of a new, water-sensitive urban design approach to managing rainwater sustainably.

The ultimate goal is to harness innovative technology to improve the overall quality of the water on the island and for Singaporeans to appreciate the precious natural resource. A long-term initiative, over 100 locations have been identified for project implementation in phases by 2030. With 20 projects already complete, people have been brought closer to water.

Along Kallang River, one of the main river tributaries in Singapore, the previously named Bishan Park was earmarked as a potential flagship project during the Master Planning Stage of the Nation’s Central Water Catchment. It was conceived not just as a 62-hectare park and a 3-km long canal in need of drainage upgrading but rather to be integrated and interdependent.

As such, the boundaries of responsibility need to be redefined between the National Parks Board (NParks) who are responsible for the park and Singapore’s National Water Agency (PUB) who are responsible for the canal. For the first time, the two agencies worked together to manage the river park, proving to be a good opportunity for both agencies to combine resources and meet their goals of providing outstanding open green spaces for recreation and health while managing Singapore’s water resources effectively.

For this collaboration to be fruitful, regular workshops were held throughout the entire design process to foster integrated thinking, to stimulate consensus and to form joint goals.

Top right: Dragonfly

Bottom: People can enjoy recreational activities along the river

ENHANCEMENT OF THE NATURAL AND BUILT LANDSCAPE

A unique plan to break the concrete channel and create a naturalised waterway was conceived for the first time in Singapore for Kallang River.

Designed on the basis of a floodplain concept, people can enjoy recreational activities along the river banks during dry weather and during heavy rain the land adjacent to the river doubles up as a conveyance channel, increasing carrying capacity by 40%. This enables multiple use of land within the park, creating more space for the community as well as ecologically valuable and diverse habitats.

To date, it has seen the park’s biodiversity increase by 30% with 66 species of wildflowers, 59 species of birds and 22 species of dragonfly identified – with some confirmed as rare in a city environment. In the past year, otters which are usually seen at the coast have been sighted in the man-made river, in the heart of the island, a true testament of the enviroment created.

As wildlife is brought back into the city and chances for appreciation and interaction increase, stewardship towards the environment is inspired.

ART, CULTURE AND HERITAGE

An outstanding element of the new park is a 4-metre high lookout point by the river called Recycle Hill. Concrete from the old canal was reused to build the hill. This not only added a new aesthetic to the place, but also acts as a reminder of its heritage and history. At the same time, the winning entry of the nation-wide sculpture competition held in 2009, ‘An Enclosure For A Swing’ by local sculptor Kelvin Lim Fun Kit was commissioned to be positioned atop the hill in commemoration.

The park itself is the neighbourhood’s backyard. It is a place for different racial groups, the young and the old alike to mingle and practice tai-chi, play football, garden and jog or just enjoy the park and river. An increasingly recognisable part of Singapore’s landscape, the park’s substantial event lawns are also the stage for large community festivals and events like World Water Day, Community Art Celebration and Mid-Autumn Festival as well as smaller intimate events like weddings and birthday parties.

ENVIRONMENTAL BEST PRACTICES

In an effort to promote environmental sustainability and management, numerous ‘green’ innovative methods were introduced into the making of this pilot project.

Top Right: Circulation diagram of the cleansing biotope

Bottom right: Cleansing biotope

The use of soil bioengineering is a first for Singapore. This involves the use of a combination of natural indigenous materials along with engineering methods for bank stabilisation and erosion control. A seamless blend between the green and the blue environment is achieved and an enhanced habitat is created for wildlife and visitors. These methods are more cost-efficient to install and economically viable to maintain than concrete structures in the long term.

Other green developments include vegetated swales and green roofs, where drought-tolerant plants are especially selected to minimise the reliance on irrigation.

Another innovative addition is the introduction of a cleansing biotope. The biotope offers effective water cleaning treatment through natural means that uses plants and substrates to filter pollutants and absorb nutrients. The pond water is monitored, tested and has significantly improved. The water is then pumped to a new water playground constructed downstream for visitors to learn the importance of clean water through a fun and engaging approach.

With the widening of the river, some trees were sacrificed. However, most of these were transplanted while others were salvaged for use in areas for soil-bioengineering.

Soil dug out from the site was reused as a planting medium while concrete from the old canal was recycled for the construction of the new river bed, forming the walls of the cleansing biotope and building of Recycle Hill.

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION AND EMPOWERMENT

Community engagement is a fairly new element to public realm design in Singapore. During pre-construction, a children’s educational workshop was organised where children were brought close to the water and shown the newly established fauna and flora on a test bed. The children made clay imprints, which are now integrated into one of the playgrounds. This fosters a sense of ownership between the children and the park.

Given that the park is essentially a community park, as it lies between two mature estates (Bishan and Ang Mo Kio) it has received much interest and many partnerships with local communities in the area. These range from primary schools, secondary schools and junior colleges to senior citizen groups and community centres. The different groups bring various dynamics and life to the park.

For example, students volunteer regularly to keep the park and river clean, and one school, Raes Institution, has even taken steps to integrate facts about the park’s water and ecology into a community learning trail. On the other spectrum, Bishan Community Centre recently organised a photography competition, drawing people to appreciate the beauty within the park.

Following the completion of the project, enthusiasm about the park has seen the formation of informal groups such as the ‘Friends of Kallang River @ Bishan Park’ whose activities encompass patrolling the park, having quarterly clean-ups and educating the public about the park.

Stewardship of the park and river starts from education and awareness for young and old. The direct and active involvement of the community has given them a new understanding and pride in the park, which they can pass on.

HEALTHY LIFESTYLE

The re-developed park boasts a variety of new amenities which support and promote active lifestyles. These include three new themed playgrounds, fitness areas, better toilets with showers and new playing fields. The existing dog run, community garden and foot reflexology area were also refurbished for a fresh lease of life. These amenities are located strategically at various points around the park to ensure that each neighbouring community would have a convenient yet unique outdoor recreational space within their proximity. At the same time a new Park Connector Trail links Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park to a larger nation-wide bicycle and jogging network, creating much enthusiasm for groups like Love Cycling Singapore that have organised trips along the river and through the park.

Open grass fields were intentionally designed as additional spaces for physical exercise and self-initiated play like kite flying, ball games and football. This approach of leaving ample space for self-invented activities is something new and experimental in Singapore. In addition, the tai chi grounds were expanded and large groups of tai chi practitioners can be spotted in the park every morning.

The grandest change is the waterway and the bonds people form with one another as they interact with it. Now, with its open banks, it is a common sight to see families wading in the river, catching fish, lending total strangers a hand (or a net) or just enjoying the flow of the water. Here, families are brought closer, spending time bonding outdoors.

Comments (0)