Mobility and the space dedicated to mobility amounts to the single most important factor for the liveability of cities. Or at least as seen from the point of view of travel, public spaces, aesthetics, air quality, connectivity, amenities, functionality, commuting, leisure time, coolness and climate change.

That is why, before rushing headlong towards all the new mobility innovations that seem to be sprouting up left and right these days, we had better put deep thought into what we want our cities to look like. If we could paint a grand picture of our ideal future city, how would it look?

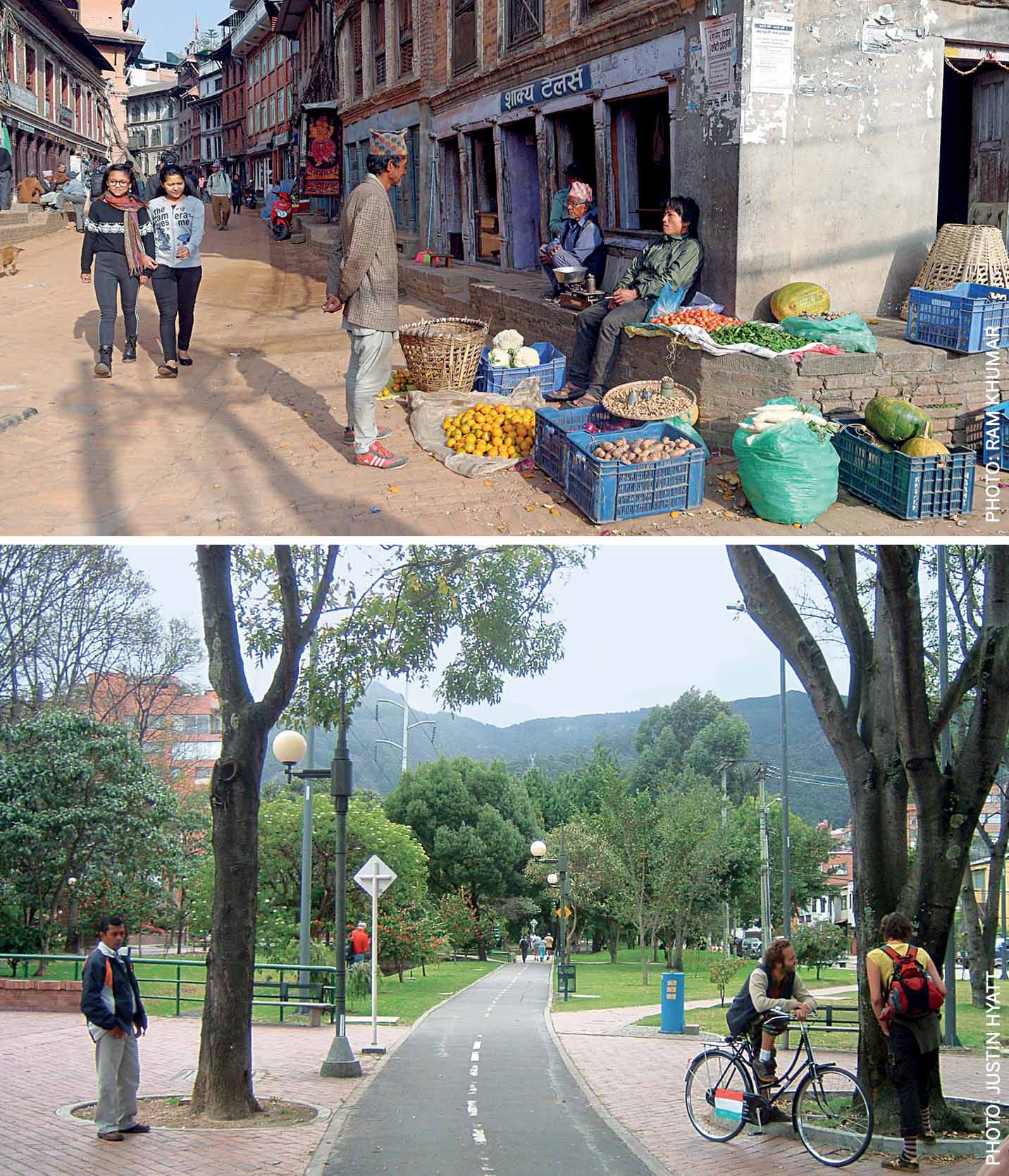

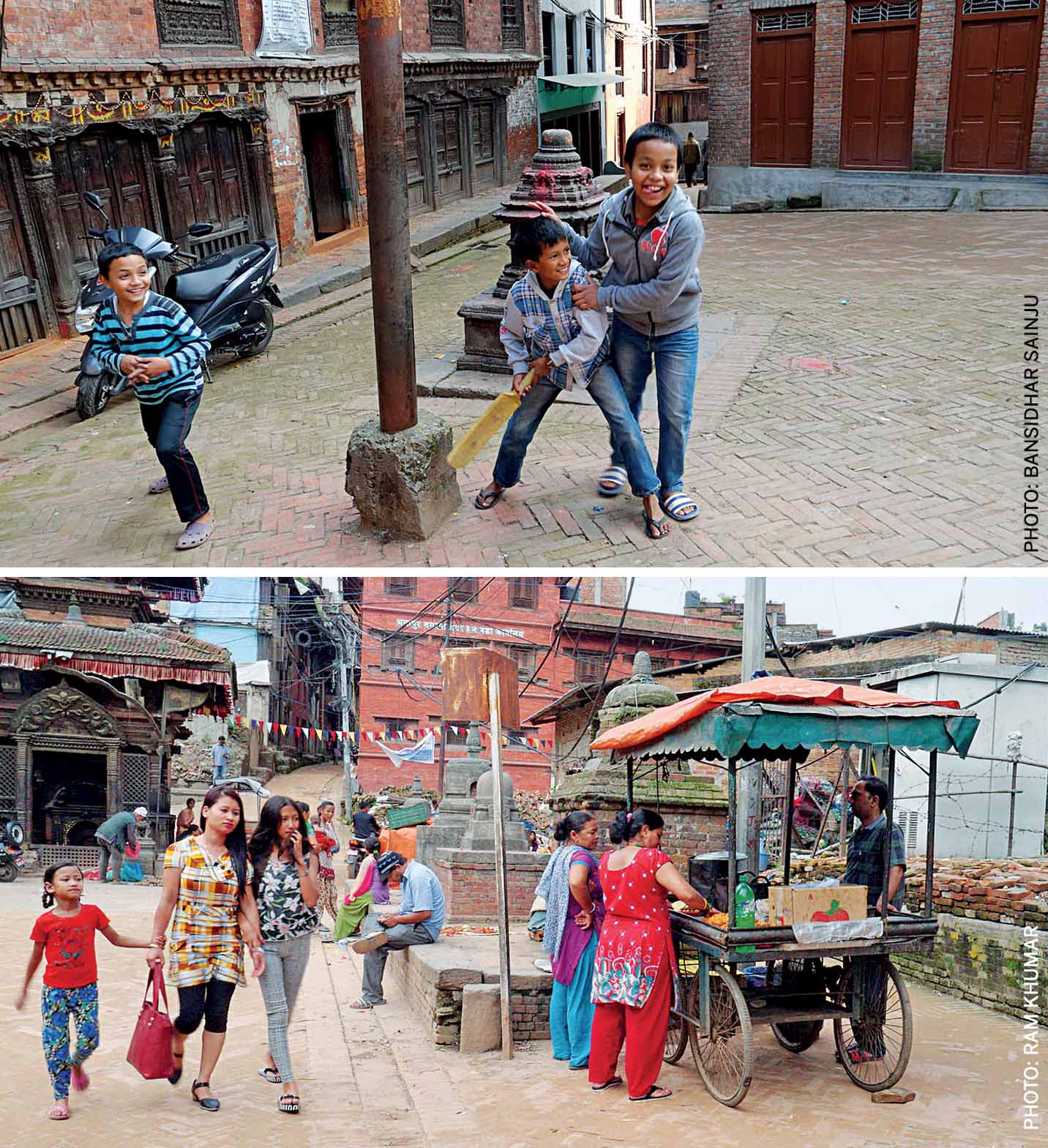

A lot of what comes to mind seems to be nearly the very opposite of what most major cities in the world have to offer these days: peace and quiet, clean air and a plethora of green, beautiful spaces to walk through or rest in. Community spirit is about knowing your neighbours, being able to borrow milk or a few eggs, engaging in conversation with friends while kicking back in your local square. And finally, being able to travel from A to B with the least fuss possible.

Bottom: Linear park El Virrey in Bogotá, Colombia

Sustainable mobility has become an accepted term in the past years with more and more cities taking earnest steps to promote active travel or increase the efficiency of public transport systems, for example. The European Union supports many projects throughout Europe to improve mobility and sustainability in cities. Numerous networks of organisations and professionals now exist. Think of the CIVITAS Initiative, ICLEI and POLIS, or European Mobility Week. There are yearly conferences dedicated to Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs), to freight movement, pricing policies as well as bike share systems.

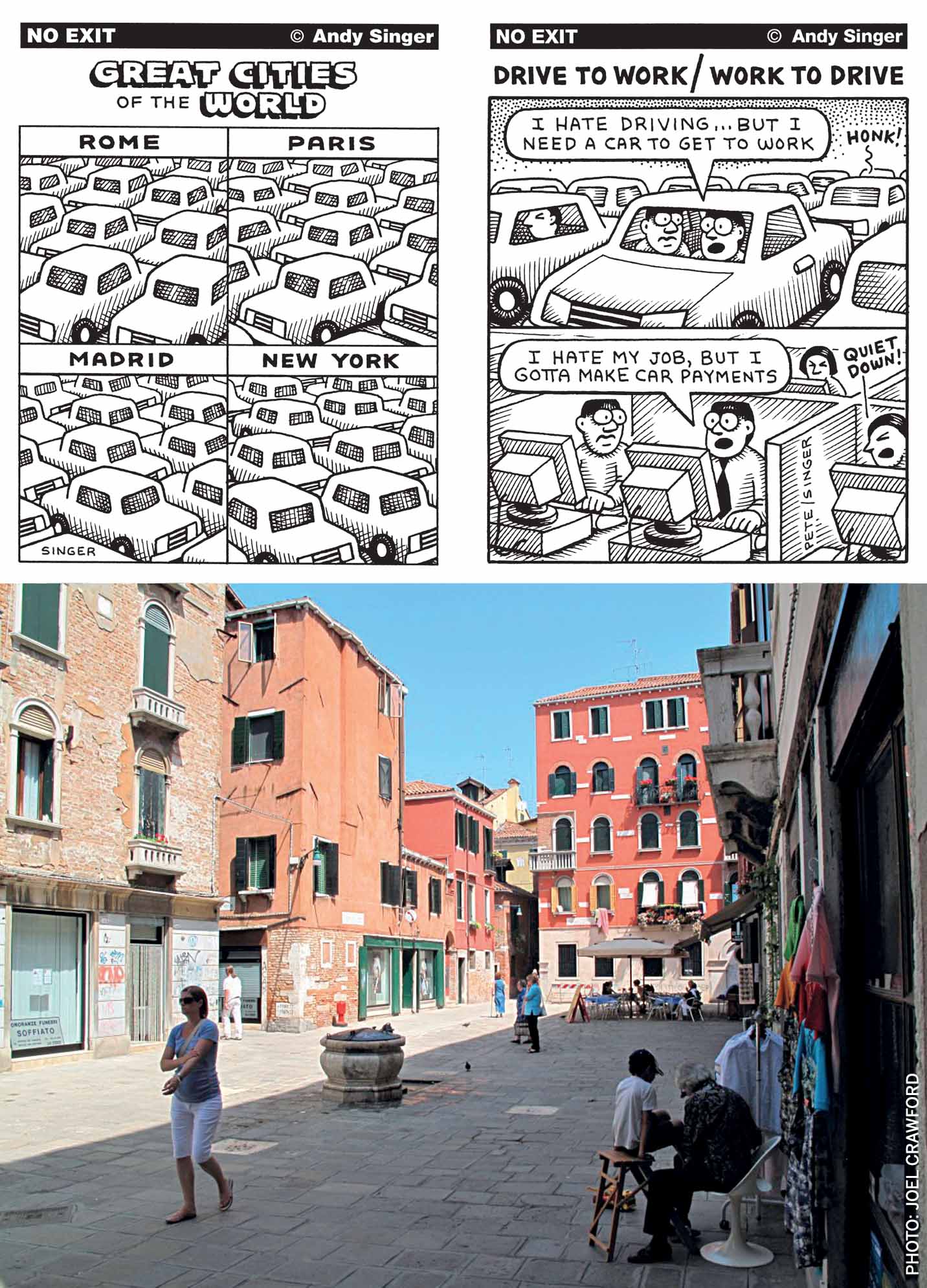

While not meaning to take anything away from the many noteworthy accomplishments, we come to the next point: the existence of one single instrument that can be implemented rather quickly, with the capacity to deal a harder hitting impact than most other measures put together: the whole-scale removal of cars from our streets.

If we could paint a grand picture of our ideal future city, how would it look?

This piece is certainly not the first one to make such a suggestion. Earlier this year, articles appearing in both the World Economic Forum (WEF) and New York Times have suggested as much. The latter arguing point-blank that, “cars are ruining our cities” including the now familiar logic that adding extra lanes to a freeway does not relieve congestion, but induces even more traffic (‘induced demand’), and that traffic calming (such as narrowing lanes of traffic or closing access to a road) has the actual effect of relieving traffic congestion – known as ‘traffic evaporation’. The former Mexican president Felipe Calderon is quoted in the WEF article saying that cities should be redesigned so that they do not need cars.

Just for the record: by eliminating or at least greatly reducing the amount of car traffic in urban areas, you can knock down all nine bowling pins with one throw. Imagine the after picture: getting from A to B will become very easy, as your choice of cycling, public transit and walking all work superbly without cars and traffic jams to slow them down. Public space and parks have become ubiquitous, the city now has more places than ever to relax on the grass or socialise with friends and neighbours in public squares. The air you breathe is now as fresh as pristine Alpine air. A huge winner is the sense of community in your neighbourhood. Levels of trust and interaction have grown, people help each other and crime is at an all time low. Children play in the streets again. And the cherry on the top is that vision zero has been achieved: no more traffic crashes with deaths or serious injury to report.

While that might seem like a Utopian concept, let us not forget that a community’s collective vision, if campaigned for energetically, has at least a fighting chance of turning into reality. Ask the German organisers of Volksentscheid Fahrrad. They have been using grass roots campaigns to instigate public support and a legal framework for making German cities truly cycle-friendly; preparing bike laws that can be enshrined in a city’s sanctioned development programme. And they have been successful. Thus, it is important to carefully examine our vision of the future of cities and then work toward that vision with resolve.

Eliminating all diesel and conventionally powered cars and replacing them with electric or Automated Vehicles (AVs) will only address a fraction of the current problems. Before citizens of this planet sign off on a vision of a bright future dominated by electro-mobility and automation, we need to make fundamental decisions about land use and the design of our streetscape. What proportion should be reserved for mobility, how much afforded to community spaces, parks and vibrant green spots?

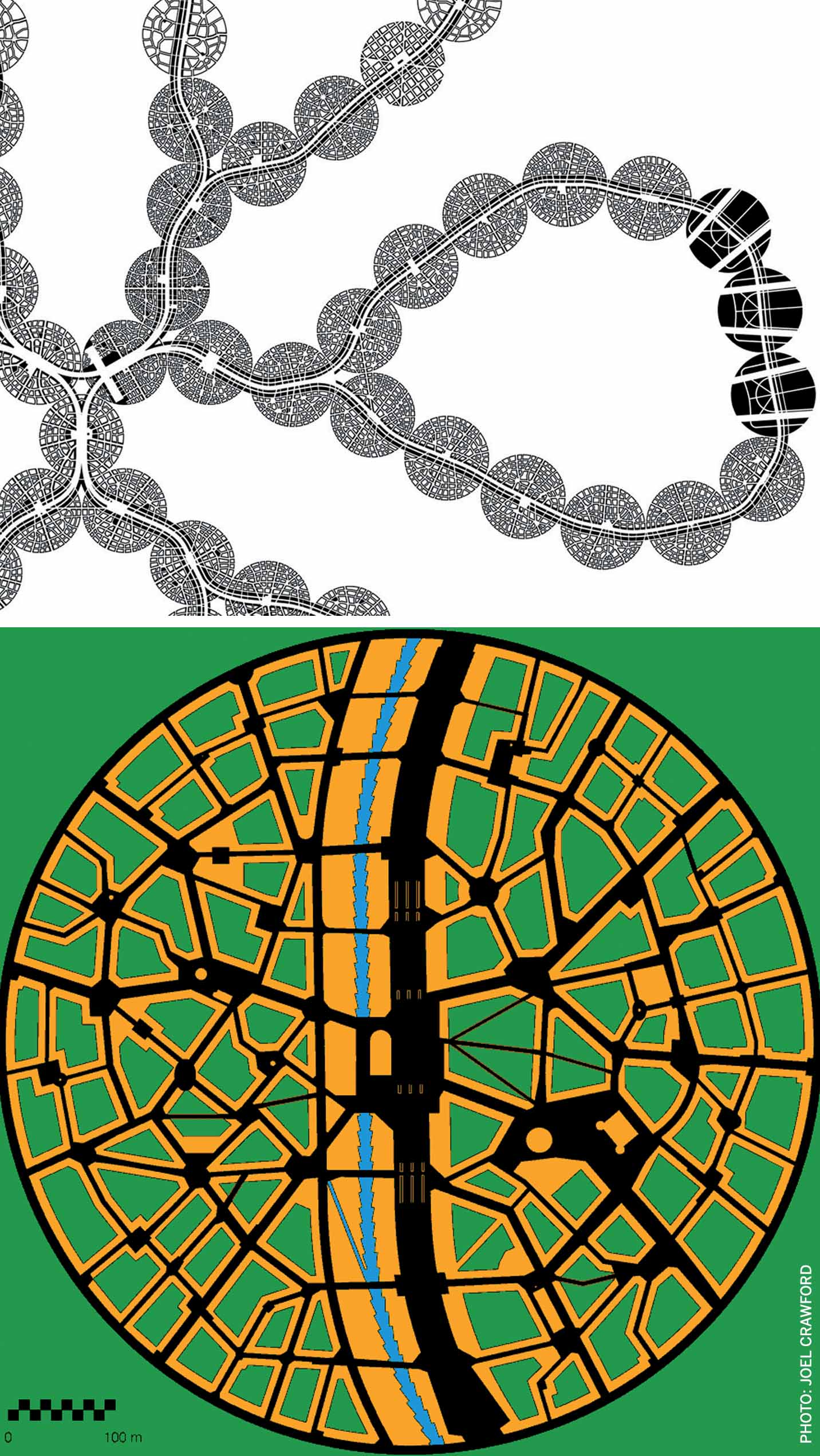

Joel Crawford, in his seminal works Carfree Cities and Carfree Design Manual provides a blueprint for designing cities completely without cars. The meticulously elaborated design of carfree cities follows a lot of the design typologies that make sense once cars have been removed: in the city of short distances, everything is in easy reach. Public transportation forms the backbone of transportation needs. Streets and built areas are narrow and follow the general pattern of organically developed European medieval cities. All residential buildings have front door direct connection to the street network, while via your back door you may access a sizeable green space, suitable for relaxation, gardening, Spanish guitar lessons, you name it.

By eliminating or at least greatly reducing the amount of car traffic in urban areas, you can knock down all nine bowling pins with one throw

Given the need both for new cities to be built as well as re-configuring our existing cities, it appears there is quite a lot to do. It is a good thing some places have already gotten started. Venice, Italy, is not only a gem, but also a fully functioning model of a carfree city that already exists and offers proof that it can work. Fes-al-Bali in Morocco has the largest known carfree urban area in the world, with 156,000 inhabitants. The Vauban district of Freiburg, Germany, is the largest new carfree urban development, however it’s not the only one.

Currently, one city with particularly high ambitions is Oslo, Norway. The city only seriously took on the case of removing cars and promoting cycling in the past five years. Yet they are following a plan to convert most of the downtown area into a carfree zone by 2019, with the removal of parking and the banning of diesel from the entirety of central Oslo. Their approach has been to go street by street, removing parking for cars and adding painted bike lanes.

Meanwhile, Barcelona (Spain) has begun implementing the ‘superblock’ model, which redevelops an existing grid design to eliminate through traffic for the majority of streets and allow neighbourhoods to function with only local traffic. Once completed, this model is supposed to reduce automobile traffic in the affected areas by 80%. Other cities in Europe are also undergoing exciting changes. It is worthwhile to keep an eye on cities such as Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Paris, Brussels and Berlin, as well as numerous smaller cities like Vitoria-Gasteiz in Spain or Tallinn in Estonia.

Bottom: Streetscape in Bhaktapur, Nepal

The developed world is by no means the only part of the globe with an interest in sustainable mobility and carfree cities. Bogotá, Colombia, has attained remarkable achievements. They have implemented hundreds of kilometres of bicycle paths throughout the city since the beginning of the 2000s and can boast of the now famous TransMilenio – the original Bus Rapid Transit (BRT). Ciclovía is like a big street party, enjoyed by two million citizens on over 120 km of the city’s streets; a temporary carfree conversion every single Sunday of the year.

For over a decade, the city of Dhaka, Bangladesh, has seen a rising tide of carfree and transport activists: the organisation Work for a Better Bangladesh (WBB) Trust has been promoting non-motorised transport since 2004 and more recently its affiliate, the Institute of Wellbeing, helped launch the Carfree Cities Alliance Bangladesh, which plans to capitalise on the fact that less than 10% of daily trips are made using cars.

The problems of motorisation are however very visible on the city’s major thoroughfares, yet some residential neighbourhoods still have next to no motorised traffic. This is in part due to the fact that Dhaka serves as the bicycle-rickshaw capital of the world.

Multiple cities are being planned in the next few decades by the Government of Nepal. There is already interest in the feasibility of applying a carfree design to at least some of these cities. This would build on the traditional urban settlement patterns in many Nepali cities, where there is a low level of vehicular traffic. Foot traffic reigns supreme and most business is conducted right on the street. Nepalese carfree advocate Shail Shrestha believes that Nepal has the potential to develop as a model country blueprint for carfree cities on a wide scale.

India is also a place to watch as the Indian government has launched an ambitious de-velopment agenda for 2030 and embraces resilience and the creation of 100 smart cities. This may well provide a golden opportunity to restructure transport systems, which local activists, from Delhi to Bengaluru, are keen to support.

It is firmly believed that if the full potential and viability of carfree cities are properly realised, there would be a much stronger demand for it. On most occasions when new projects are proposed, bearing elements of carfree spaces or a reduction in traffic, there is always predictable opposition from a vocal minority. Yet almost without fail, every time a new pedestrian zone pops up and takes hold, the level of acceptance mushrooms, with people clamouring for more.

However, in order to make serious progress towards achieving (largely) carfree cities in the near to mid future, it will require citizens to engage a visioning process: how do we want our cities to develop? It will require forward-thinking leaders and city governments, who are not afraid of taking bold steps and realising that many measures will switch from unpopular to popular, once the astounding results begin to materialise. Finally, it will require a whole army of activists and advocates, including urbanists, planners, architects and designers, who are unafraid to take the more radical approach and not settle for solutions that bring only mild improvements to the quality of life in cities.

Comments (0)