‘Healing environment’ is the umbrella term for the environmental factors that can positively influence patient well-being in hospitals and other medical institutions. In this brief article I will investigate the possible uses of landscape, trees and plants in hospital environments. My aim is to show what is already known, what we can learn from successful examples and what opportunities and challenges lie ahead.

Our behaviour and well-being are – often without us being aware of it – influenced by the spaces in which we find ourselves. Within the field of environmental psychology the ongoing search for relationships between physical environment and behaviour aims to identify best practices for designing these spaces. Research examples are children’s learning behaviour under different lighting conditions, the incidence of vandalism in well-kept versus neglected public spaces and the relationship between purchasing behaviour and background music, ambient temperature or smell. The influence of greenery and nature on people’s well-being is another, related domain of study.

A distinction can be drawn between factors that directly influence the functioning of the human body and factors that have a more roundabout influence on our actions and health. Light, air quality and temperature exert an influence on respiration, vision and agility, amounting to a direct influence. Indirect factors such as ambient colour, smell, complexity and tidiness can stimulate or dampen behaviour, but are less strict preconditions (as it is possible to get by with more or less of it). Still, these factors merit further study and are especially relevant for designers, as the outcomes could enable them to enrich their designs and make them more original and effective. Among these factors are the presence of trees, plants and the visible presence of surrounding greenery.

Unlike other factors, for example colour, that can have both a positive and a negative influence, the reported effects of greenery are almost, without exception, positive. No surprise then that the presence of greenery and nature has gained recognition as an important factor within the healing environment.

A brief historical digression is needed here. Since ancient times, nature has played a key role in healthcare. In the absence of modern techniques, doctors more often than not resorted to supernatural and spiritual forces. They also made extensive use of plants and herbs. In fact, surprisingly early on in history, discoveries were made that led to treatments still in use today, like using willow bark containing salicylic acid, the active compound in aspirin, or vitamin C from plants and fruits. It was only in the 19th century that, thanks to improved laboratory techniques and advances in virology and bacteriology, modern healthcare as we know it gained momentum.

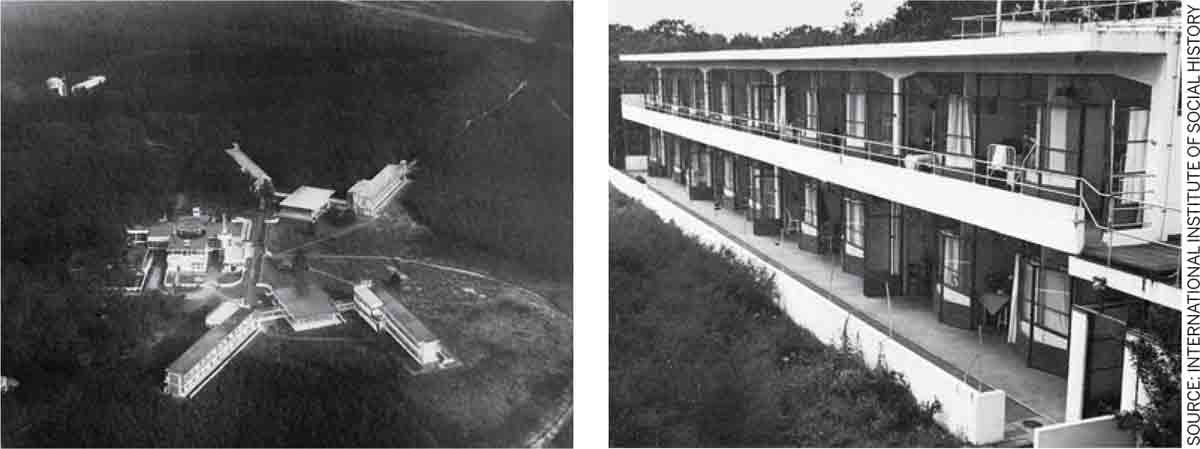

However, the interest in nature’s role in healthcare did not diminish. Towards the end of the 19th century, with tuberculosis running rampant, a vacation in natural surroundings with plenty of fresh air and sunshine was seen as good therapy. From 1840 onwards the first European sanatoriums in wooded and alpine regions were established. In the Netherlands, the Volkssanatiorum (‘people’s sanatorium’) in Hellendoorn (est. 1901) and the Zonnestraal (‘sunray’) in Hilversum (ca. 1930) were prime examples. Zonnestraal is interesting for two reasons: the covered open rooms where patients could spend as much time as possible outdoors as part of their treatment and the remarkable way in which building and landscape seamlessly merged, allowing for the best possible interaction with the surrounding greenery.

Over the course of the 20th century, hospitals went through major changes. With growing affluence and social change, healthcare became accessible to increasingly large segments of the population. This in turn necessitated the building of larger, more modern and efficient buildings. Established buildings were extended over their existing premises and new, modern medical centres were built, in both cases with large, stony complexes as a result. Even now, functionality, the availability of sufficiently qualified staff, cost control, the pressures of time and overall performance dominate other considerations such as aesthetics and liveability.

In spite of this, or perhaps as a reaction to it, the last decades have seen an increase in the attention paid to the human aspect of hospitals, including deliberate greening of the hospital environment. Scientific research offers clear support for the use of greenery in this manner. As early as 1984, Ulrich (presently professor at the department of Architecture and Centre for Healthcare Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology) investigated the relationship between the time spent in a hospital with greenery vs. bare and stony hospital environments. Ulrich’s research was followed up by, among others, Agnes van den Berg (University of Groningen).

PHOTOS: MILAD PALLESH /VANDERSALM-AIM

The hospital environment turns out to have a measurable influence on patients’ stress levels, blood pressure and heart activity. Several studies have shown that in hospitals where patients have greenery within clear view, the average number of days spent in the hospital is lower and the intake of painkillers is reduced. In this case, greening the hospital environment kills two birds with one stone: reduced cost of care and increased well-being of not only the patients, but also the visitors and staff. An increasing focus on these advantages may help to offset the disadvantages that are often put forward, such as buildings in green surroundings requiring more, often scarce and therefore costly space, underground parking being costlier than parking at ground level.

There are roughly three different applications of greenery that deserve mention here: outside greenery within clear view of patients, green indoor and outdoor spaces and placing plants (and trees) in semi-public spaces within hospital buildings. Where setting up a green landscape is impossible, simulation can serve as a surprisingly effective substitute, as we shall see shortly. Gardens accessible to patients add value by stimulating their senses, allowing them to see and also feel, smell and hear nature.

Parks and promenade gardens promote physical exercise and social interaction, thereby influencing patients’ health and well-being in a positive way.

Much less drastic – and correspondingly simpler to implement – are plants (and trees) within buildings. In addition to offering a friendlier general aspect, plants can help improve air quality, routing and orientation. The often-heard objection that plants negatively affect hygiene can easily be tackled by using expanded clay pebbles.

Present developments

In the context of green hospitals, the discussion often revolves around new developments in green settings where architects and landscape designers work closely together towards a good integration between a building and the surrounding nature. Of course, this presupposes the availability of a suitable location. Perhaps more interesting and relevant here is the fact that much can be accomplished already in and around existing buildings in stony environments, for example by laying out roof gardens and green atriums.

The Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam, an existing building in a highly urbanised area, is a good example of this approach. Together with landscape architects Juurlink [+] Geluk, the first major steps have been taken towards the greening of both the surroundings and the interior of the hospital. On the hospital’s roof surfaces gardens accessible to patients are being laid out, including fully-grown trees planted in a thick layer of topsoil. Through the application of a large number of plants the atrium has been given a more friendly appearance, while the plazas around the building have been enhanced by newly planted trees. An ongoing information campaign by the hospital tries to raise public awareness of the project. In parallel, a crowd-funding project has been set up to raise money for the roof gardens. In this way the hospital clearly shows that it has patient well-being very much at heart.

Another outstanding example in an urban environment is a sky garden situated on the 11th floor of a 25-storey children’s hospital in Chicago. In the absence of sufficient repurposable outdoor space, one of the clinic floors has been transformed into a garden floor where young patients can imagine themselves to be in a natural, calming environment. The floor has become a safe haven where they can let their impatience take a back seat and give free rein to their fantasy.

Simulated views of trees or natural landscapes turn out to have a positive effect remarkably similar to that of real nature.

A green, calming atmosphere can indeed be created artificially. Nature is unambiguous and has a positive effect on nearly everyone, even when what they see is only a projected image of it. It is far better than the use of abstract art or a pronounced use of colour that will not meet with universal appreciation and will sometimes even arouse unwanted associations, fear or gloom.

The day-surgery centre of the VU Medisch Centrum in Amsterdam has decided to make full use of the remarkable effects of simulated nature. In their surgery building, designed by D/DOCK Design, all patient experience components are addressed. Among other things, this becomes visible in the organic shapes, the carefully chosen materials and the patient-controlled curtains and lighting. A striking feature is the long, translucent wall showing slowly moving images of plants. The artificial lighting approximates natural daylight as closely as possible. The ceilings above the hospital beds have been screen-printed with pictures of tree crowns as seen from the ground, giving off the impression that patients are actually lying on the forest floor. This makes for a much more pleasant waiting and waking-up experience than under the fluorescent tube lighting that most patients in hospitals still have to endure.

IMAGE SOURCE: JUURLINK [+] GELUK EN EGM ARCHITECTEN

Green surgery rooms

The Ter Gooi Ziekenhuis (hospital) in Hilversum has taken a remarkably adventurous step by moving surgery rooms out of the hospital and into the surrounding landscape. In this case it was the oncology department that took the initiative for erecting a half-open pavilion where, during nine months of the year, with sufficiently clement weather, patients can undergo chemotherapy surrounded by nature. The project was motivated by a desire to improve patients’ well-being and reduce the seriousness of post-treatment residual effects and complaints. A welcome direct effect has been that patients report feeling less ill in what has rather unceremoniously been dubbed the chemotuin (chemo garden) than in traditional surgery rooms. The design, by VANDERSALM-aim, has been greeted with great enthusiasm by the patients involved.

Bottom: Through the application of a large number of plants the atrium has been given a more friendly appearance

In the Hilversum hospital, chemotherapy, in most cases mainly accompanied by negative associations, has become a more positive and, in some cases, even relaxing experience. Another thing that deserves mention here is the active involvement of patients in the design of the layout of the pavilion.

The examples presented above show the surprisingly large range of possible uses of nature and greenery in and around hospitals. Research into clinical outcomes and economic outcomes increasingly points to the advantages of greening the hospital environment. I believe, in the not too distant future, architects and landscape designers will, in conjunction with their clients, come to see nature in and around hospitals as a, dare I say it, natural precondition. An image-enhancing development for the hospitals themselves but also, and more importantly, a crucial and manageable step towards greater patient well-being.

Comments (0)