In the last couple of years your studio has researched the design and structure of several old housing (and mixed-use) urban projects. What can we learn from this study?

Our research project, In the Name of Housing, attempts to provide a framework to question the top-down quantitative prescription of policy as an approach to the creation of housing. This has led to the setting up of models like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), which on paper offers parity of space for residents, but actually results in inhuman and apathetic living conditions.

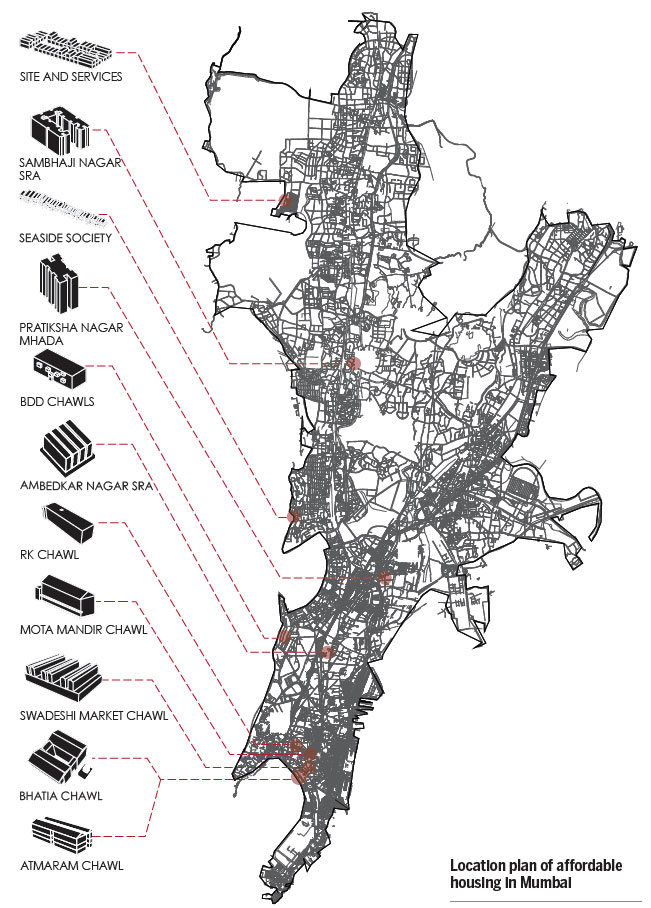

Our research sifted through the fabric of Mumbai, excavating historical and current models of affordable housing tucked deep within the city. The research compares 11 housing projects through mediums of open space, social space, circulation space, built areas and densities using drawings, sketches and models to highlight and illustrate their projective capacities. Our focus was to document the potential of existing and emergent architectural types native to our context, as a means to inform new or hybrid models for the design of affordable housing. We are, in a sense, arguing for architectural proclivity to inform regulatory mechanisms, which in turn would then feed into policy frameworks along with considerations of tenure, occupancy and equitable allocation. As a result, a desired built and spatial form then influences the framing of a housing policy from the bottom up, rather than the other way round.

The data for this study was collected through fieldwork that entailed measured drawings, interviews with residents and observations at each of the sites. The format of the exhibition that preceded the publication allowed for each project to be compared across ten factors: Location, Building Form, Circulation, Programme, Tenure, Community, Floor Plans, Envelope, Unit Plans and Analysis. In a departure from the structure of the exhibition, our book presents the research of the projects as individual case studies.

In the Name of Housing initially started as research into the architecture of affordable housing types as background material for a design project in our studio. While we found that there were many narratives that described the socio-cultural life, there was very little quantification of the architecture that enabled this fabric to exist. Our biggest learning was that the much-eulogised social life was a product of a specific architectural framework as much as it was the other way round.

Appropriations that people made transformed particular types of habitations creating new hybrid configurations of the old and new.

During your research, did you discover any specific common factors among the areas you focused on?

The more time we spent in the field looking specifically at the form of these projects, the more instructive they became, both through the breadth of their variations, as well as the depth of their spatial and formal engagements. The analytical diagrams and drawings in the book further galvanised our belief that these frameworks, however unique, still seem to gravitate around certain emergent commonalities like:

• Networks

• Systemic Openness

• Shared Space

• Extended Domesticity

• Detail

NETWORKS

Swadeshi Market Chawl (Kalbadevi)

The responsiveness of architecture to the streets and vice-versa is integral in the formation of a symbiotic housing system, further enriching the economics and the quality of lifestyle of the residents.

Swadeshi Market Chawl is one example of efficient networks within the city fabric. The red lines are indicative of the circulation through the chawl. The grid of internal streets within a mixed-use development plot and its connectivity to the main external roads proves to be efficient within a rapidly evolving city fabric.

The double-height street accommodates traders on the ground level and a staircase connects the structure to upper levels, which is used for resting or storage.

The upper levels overlook courtyards and bridges connect one part of the chawl to another, allowing the residential block to co-exist above the commercial segment, forming a liveable example of a mixed-use development.

SYSTEMIC OPENESS

RK Chawl + Atmaram Chawl

The transformation of a grid in a residential block allows for the creation of social spaces, room for growing families and sometimes is a means of revenue. This is evident from the openness of spaces created in RK Chawl and Atmaram Chawl.

The significant feature of the Atmaram Chawl is the separation of the kitchen from the house across a corridor. This has brought about better neighbourhoods with the creation of social spaces.

Over time, such a plan has allowed space for change. The residents have moved the kitchen within the layout of their house and created a means of revenue by renting out the former kitchen space.

The remarkable thing about the open system in these structures is that the quality of spaces is retained despite the change of functions.

In the RK Chawl, the ground level has a doubly loaded corridor juxtaposed to the upper floor plan, which pushes the corridors on the outside. This sort of grid creates four sizes of units allowing the possibility for different permutations and combinations of rooms, further making space for bigger rooms for community gatherings.

This type of grid system allows for the creation of larger units, which enables people of all economic classes to live together in the same block and be a part of a diverse community.

SHARED SPACE

Bhatia Chawl + Charkop

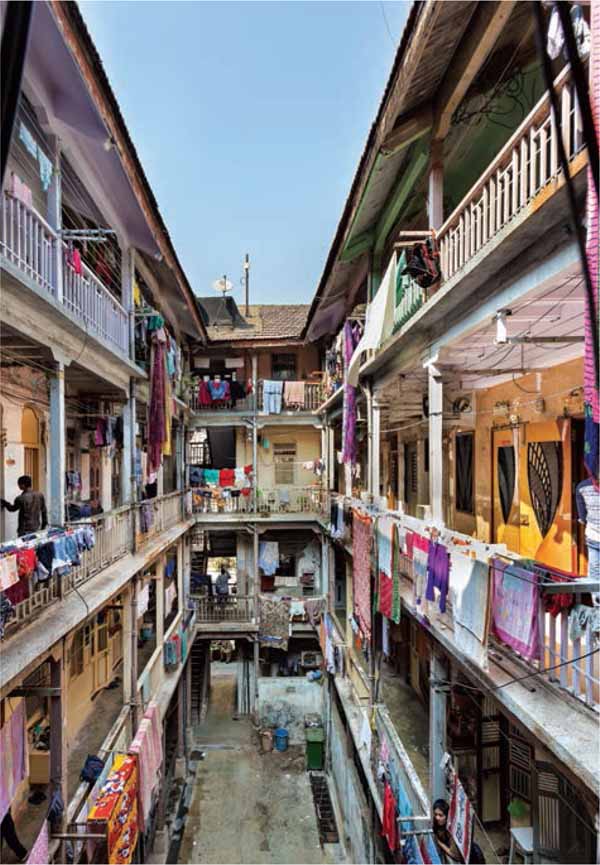

For a socio-cultural fabric to exist, it is integral for the architectural built form to have a proportion that enables the creation of flexible and amiable shared spaces.

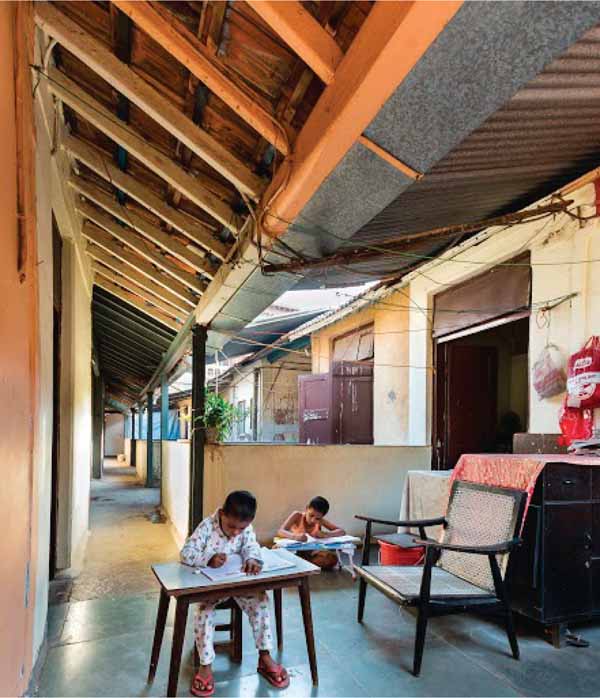

A typical courtyard-type chawl has an intimate height-to-width ratio, which acts as the social connect within the community. The shared corridors facing inwards towards the courtyard allow easy communication amongst the residents. In such spaces, the simple element of a door can transform a corridor into a more private study and the fellow residents adapt to such changes for the betterment of the community.

Bottom: Illustration showing quality and scale of shared spaces in Bhatia Chawl

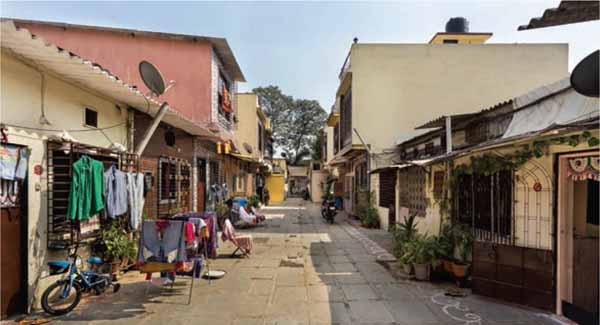

Another example of shared spaces is the site and services project in Charkop. It is a combination of 40 square metre and 25 square metre plots, some facing the main road, some flanking the three-metre-wide road and some lined up near an extended courtyard. Originally, they were all ground storey structures, but as the community acquired a diverse character over the years, some of the individual owners expanded vertically with the addition of a first floor, considering the height restriction of about 14 feet.

Even after so many years, the shared space of the three-metre-wide road and the extended courtyard is free of encroachment and is still used collectively.

EXTENDED DOMESTICITY

BDD Chawl

The extended home is a prerequisite to multigenerational families for liveability.

Each chawl building is a rectangular block with a spacious corridor running across its length, houses flanking on both sides and a shared toilet block at the far end. The tendency of domestic expansion has been noticed in these chawls owing to the growth of families in most cases.

The simple 3-4 feet extension outside the building line, the addition of a loft within the house or conversion of the mori (drain trap) into a bathroom not only adds to the existing space, but also uplifts the quality of life of residents. More than the change itself, it instills a sense of pride amongst the residents that they have their own washrooms over a shared one or the extension of the house to form an additional room.

It is commendable that the residents have maintained their corridor space, free of any encroachment and are respectful of their prime shared space.

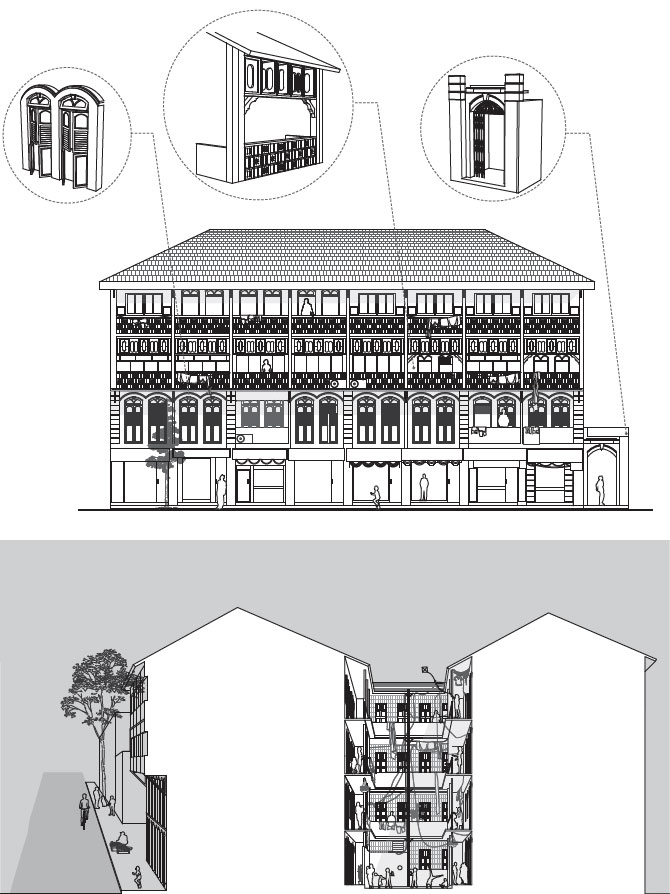

Bottom: Details of Swadeshi Chawl

DETAIL

Swadeshi+ Bhatia Chawl

The simplicity and the ingenuity of the construction details that have been incorporated in the simple architectural elements such as windows, bridges and the weather shades (chajja) are crucial to the lifespan of these chawls.

The tripartite windows are of aesthetic and functional value. The simple idea of dividing the windows in three parts to allow better airflow, visual connect and privacy enhances the liveability of the high densities in these spaces.

Most of the chawls are interconnected with bridges and the use of simple wire mesh or ventilators to cover them allows for light and air to filter through making the interiors easy to maintain.

The chawls are old structures, which are generally supported by cast iron columns and the beam edge detail is essential to fitting a weather shade, in turn protecting the internal corridors.

How has this learning process led to more innovative design? Can you give us an example of a recent project?

In most cases, the architecture of low income affordable housing whether state-built or state-enabled developer housing lacks imagination and is usually just a mathematical exercise to maximise real estate profits.

The previously mentioned five points are but a few of the many paradigms that can inform the design of affordable housing since, at present, the things that such design needs to consider, like expandability, systemic openness, live-work scenarios and sociocultural space, are largely absent. Our design project in Navi Mumbai though removed from the geographical and economic constraints of our field of investigation was fertile ground for the studio to test the relevance of our learnings in a real context.

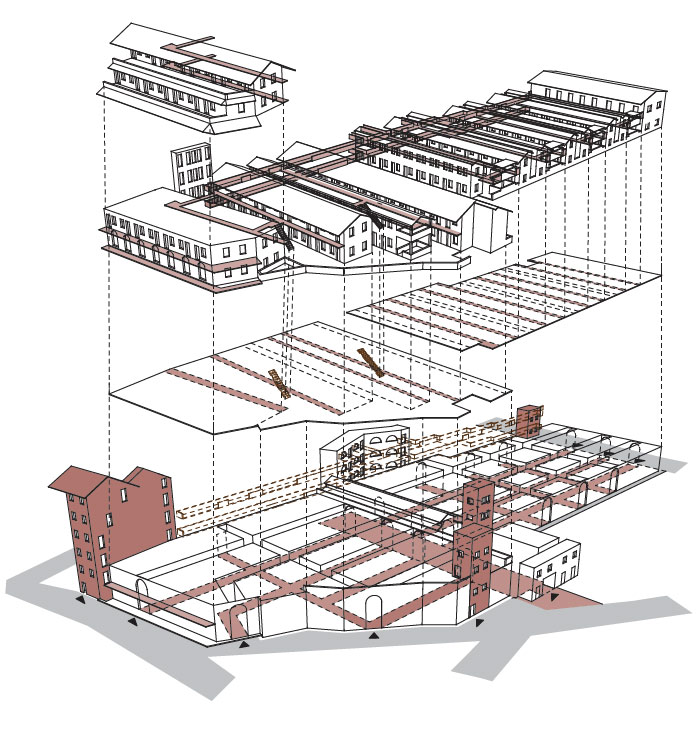

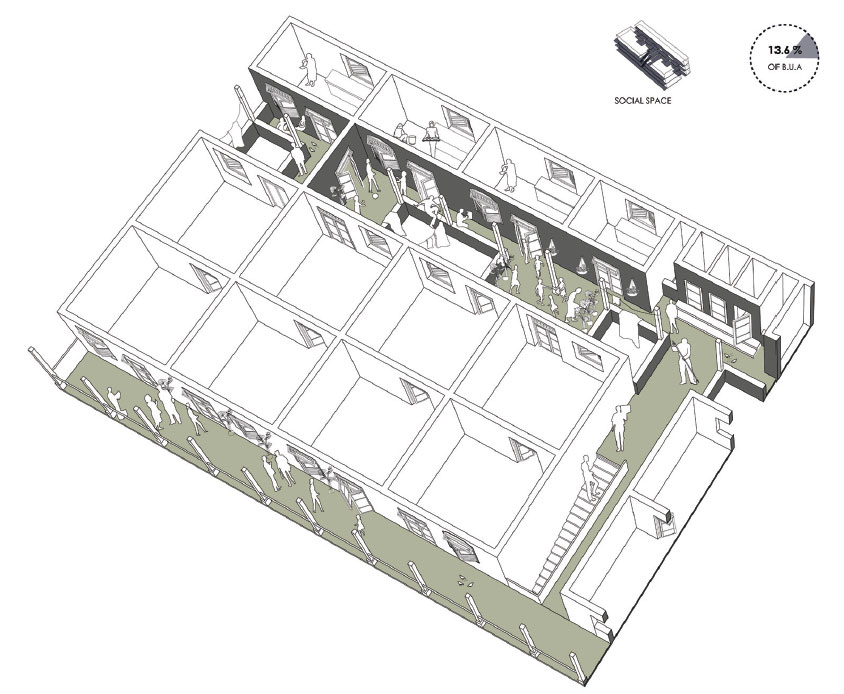

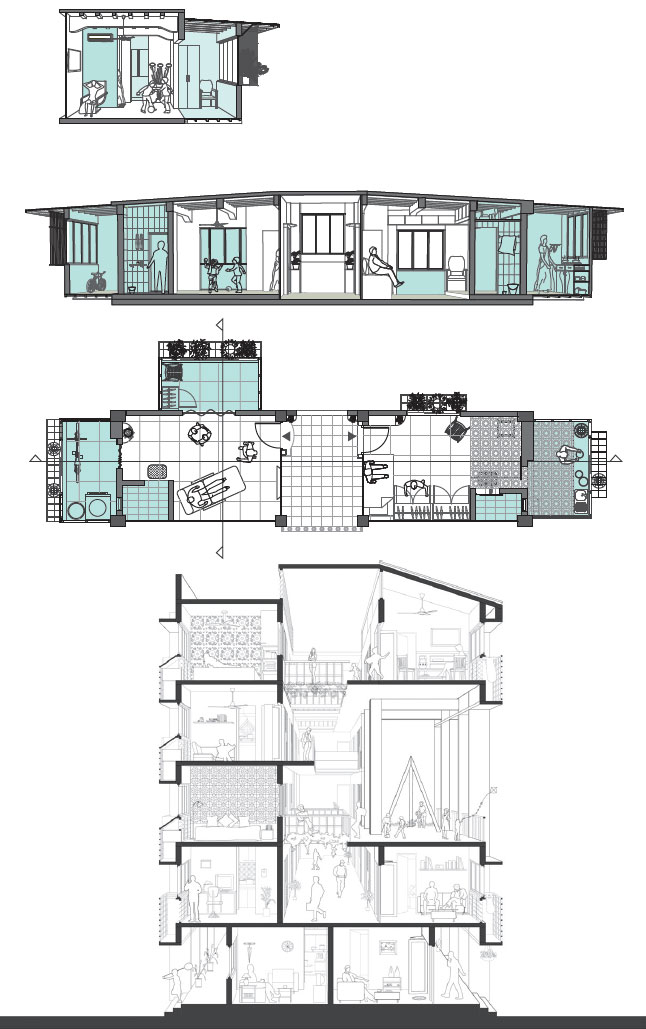

The site lies on the outskirts of Mumbai city, within walking distance from a new railway line connecting to Mumbai city via the new proposed international airport site. In a departure from the client’s initial brief we modified his mandate of designing separate buildings for one-room studios and one-bedroom units and instead consolidated them within a singular structure with interspaced, covered community terraces as social spaces with a variety of shared programmes. The ground-plus-four building is structured around a double-loaded corridor that staggers in plan every alternate floor, creating a continuous central sectional volume allowing for natural ventilation with hot air escaping from the corridor’s clearstory ventilators. Plus, unit walls along the corridor are punctuated by a secondary system of ventilators and windows. These secondary openings also allow for the possibility of residents from units communicating with others across the corridor as well as across floors should they choose to do so.

While our current research direction also investigates auto-construction as a means to build affordable housing, the pre-cast concrete construction system for the project was selected due to the client’s allied capacity of a precast company vertical. The construction system is a modified version of 3D precast concrete wet pods (kitchen and bathrooms) acting as structure with hollow core concrete slabs spanning across articulating living and sleeping spaces. Based on the learnings from the documented research projects we have anticipated the spatial and liveability needs of the residents, but the success of these strategies or their spatial and formal modifications over time will be hugely instructive only post-occupancy.

Comments (0)