An arboreal urban history

Like a significant percentage of its human population, the arboreal census of Los Angeles (LA) is dotted with immigrant species – transplanted trees that have thrived in the welcoming climate and artificially irrigated landscape of the LA River basin. The palms are an iconic example and poster-child for the immigrant trees of Los Angeles, however there are several species from around the world that have made LA their home over the centuries and contributed to shaping the landscape of the city and region.

California has a Mediterranean climate where summers are long and warm, winters are mild and rainfall is generally sparse all the year round. Before the origins of the city that stands here today, the Los Angeles River basin was a native prairie ecosystem of mainly grasses and wildflowers, with only the occasional cluster of trees framing the landscape: the native oaks and sycamores that grew close to the arroyos and streams for better access to water. With the settling of the region, first through the Spanish colonisation (beginning in the late 1700s), and then in waves of immigration through the mid-1800s, this native landscape was gradually and dramatically transformed, hosting several immigrant trees that have contributed to the city’s unique identity.

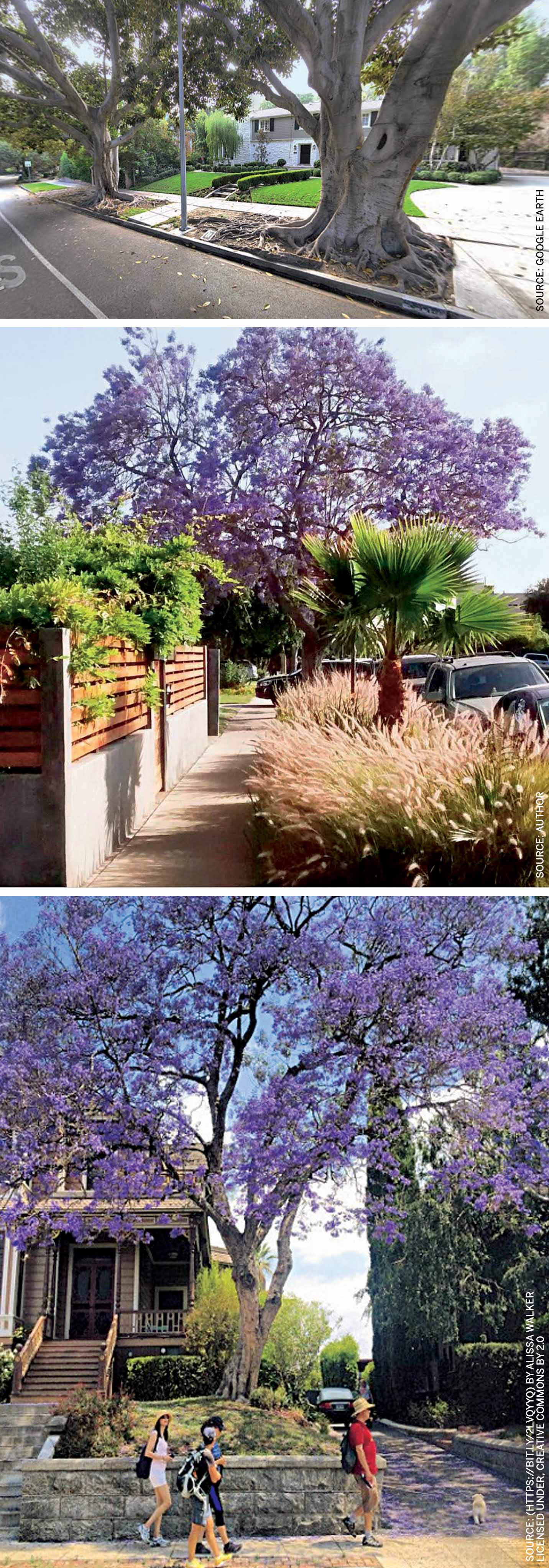

For the observant newcomer to LA, the immigrant trees are quite dominant within the urban landscape and a striking visual contrast to the native vegetation of semi-arid Southern California. Examples such as the shady pepper trees (Schinus molle) that are native to Peru, the sensory blue gum eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) and the imposing Moreton Bay fig (Ficus macrophylla) that made their way over from Australia, as well as the beautiful jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia) from South America, have their individual stories of assimilation into the landscape of Southern California. Their history and association with Los Angeles highlights the changing preferences of a city in flux.

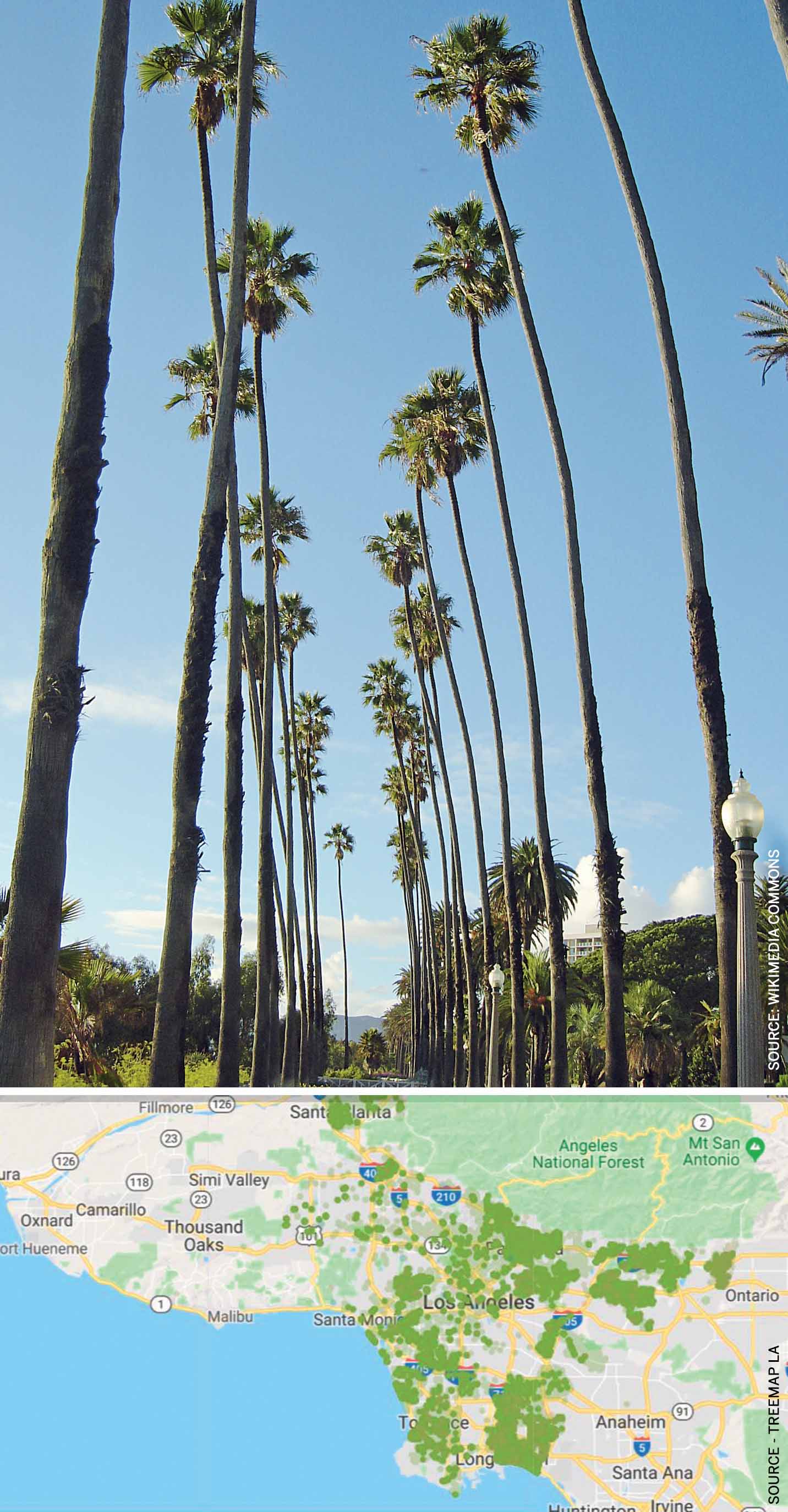

Bottom: Mapping the population of Mexican fan palms in Los Angeles

Palms: Religious props turned exotic icons

Despite their iconic association with Los Angeles, there is only one species of palms native to California: the California fan palm. Yet the most ubiquitous is the Mexican fan palm, its taller, skinnier cousin from northwestern Mexico. Non-native palms from Mexico and the Canary Islands brought by the Franciscan missionaries when they established the first colonies in the region are some of the earliest examples of immigrant species introduced in Los Angeles. The palms – requiring plenty of water to survive and providing little shade – were not well-suited to the semi-arid southern California landscape. They were instead likely introduced for religious purposes: to recreate the Holy Land in the newly colonised dominion of the Spanish settlers (several biblical verses refer to palms and their fronds were used in rituals). By the turn of the 20th century however, the palms had more than just religious appeal. With growing horticultural interest, the palm became an ornamental symbol representing the exotic sub-tropical paradise that Angelenos were projecting for their city. The completion of the first Los Angeles aqueduct under the supervision of William Mulholland in 1913 additionally ensured a steady supply of water to sustain the thirsty palms in the semi-arid region, making it possible for them to grow and propagate in an environment that, in its natural state, might never have supported them. Palms slowly but surely became a staple in ‘beautification’ and ‘street improvement’ projects across the city. A significant example of this was the massive planting project by LA’s forestry division ahead of the 1932 Olympic Games, when over 25,000 palms were planted along the streets of LA. Many of these survive to this day. The craze for palms continued to grow and expand across the region, enabling the species to completely dominate the urban landscape and identity of Los Angeles. The city’s relationship with the palms changed over time, but the early horticultural decisions and engineering advances set the stage for what would become a centuries-long obsession with these exotic immigrants.

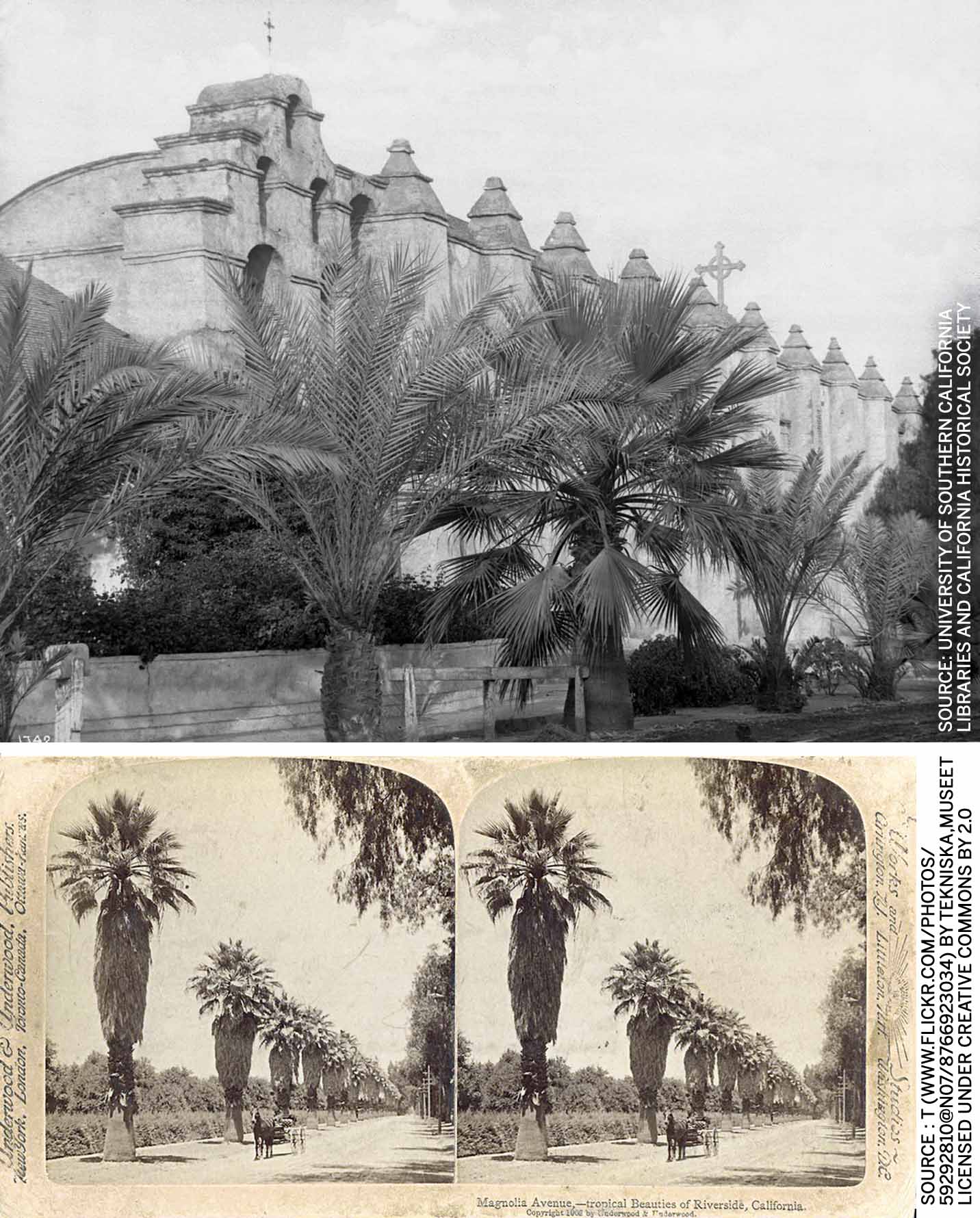

Bottom: Tropical Beauties of Riverside, California, ca.1902

The pepper and eucalyptus trees:

Workhorses that fell from grace

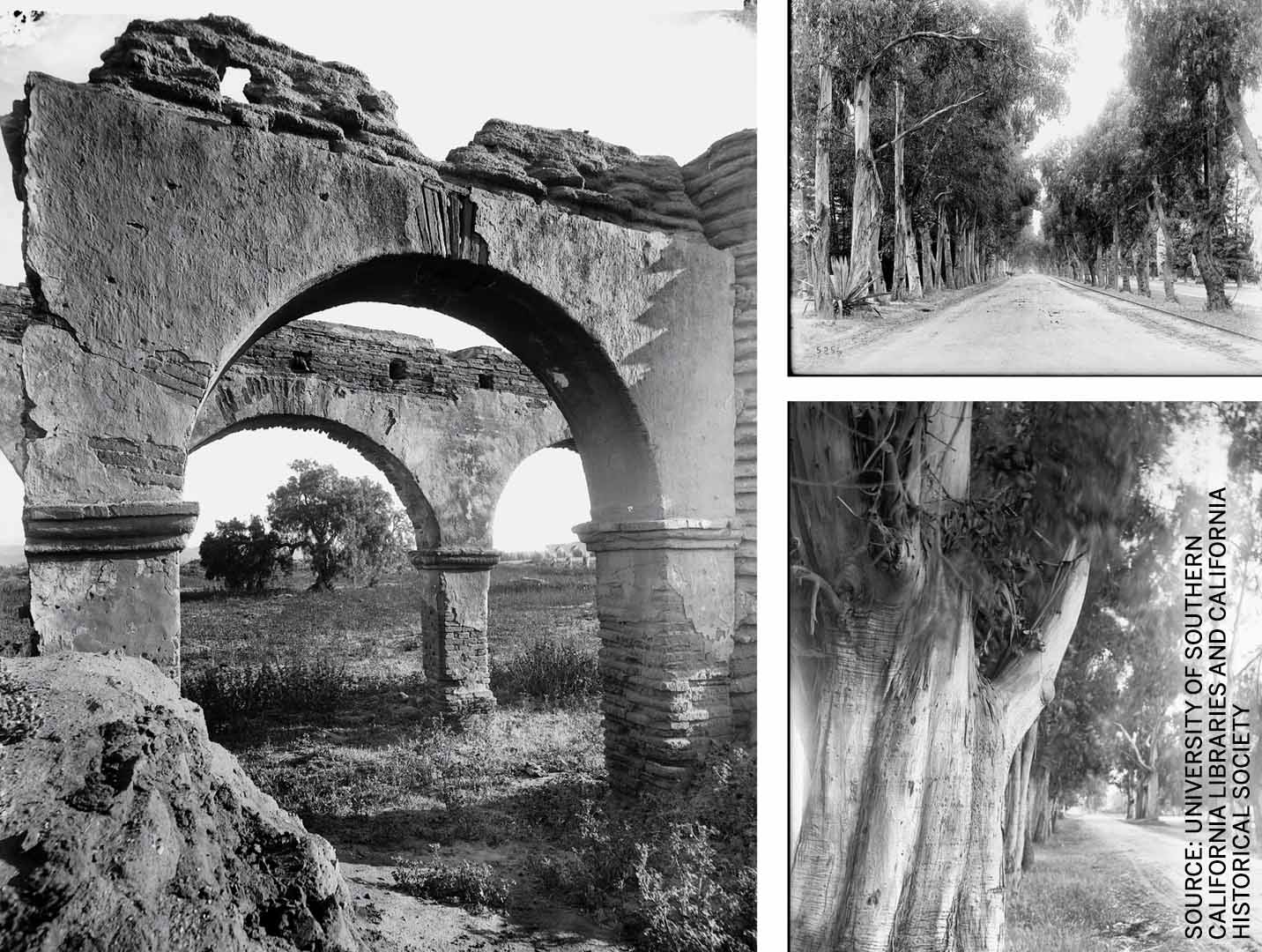

In the early decades of the settlement, the palms were more the exception than the norm in Los Angeles. As human migration to the region grew and exploded in the first half of the 19th century, settlers and wayfarers frequenting the region brought in several other immigrant trees that quickly became local favourites and trees of choice for the emerging ‘urban’ landscape. The Peruvian pepper tree and the Australian blue gum eucalyptus were prime examples of this phenomenon, but were each introduced to the region for different reasons. It is unclear how the Peruvian pepper tree made its way to Southern California; some tales speak of a seafaring captain who made a gift of its seeds to the padres at one of the early ranchos. By the mid-1800s it was gaining popularity and was being planted abundantly along thoroughfares in the Los Angeles region. Providing plenty of shade and tolerating the semi-arid conditions, the pepper tree became a successful street-tree, lining some of the most prominent thoroughfares including Marengo Avenue in Pasadena and Magnolia Avenue in Riverside in the late 1800s. The tree was cheaply available at 5 cents apiece, enabling it to take the place of more expensive species like Magnolias ($2 per tree) that the street in Riverside was originally named after. Apart from its utility, the pepper tree was also celebrated for its romanticaura and an association with the history of settlement in the region, with several early examples found in the grounds surrounding the old Spanish missions.

For the observant newcomer to LA, the immigrant trees are quite dominant within the urban landscape and a striking visual contrast to the native vegetation

The success of the pepper tree as the reigning street tree in Los Angeles was however short-lived. The incidence of black-scale insects towards the end of the 19th century led to the decline of the popularity of this species. More than the pepper trees themselves, the pests destroyed other valued immigrants: the groves of orange trees that were an important orchard crop in the early 1900s. With mounting public dislike, other flaws in the pepper trees became a subject of criticism, including their large root systems that pulled up the pavement.

Several communities replaced rows of them with the palms that were gaining prominence. Other events such as road widening for highway expansions and the Pacific Electric streetcar alignment along major thoroughfares additionally led to more trees being cut down and, eventually, the pepper tree lost its place to the palms as the street tree of choice in Los Angeles.

Top Right: Magnolia Avenue in Riverside, with pepper and eucalyptus trees ca.1900.

Bottom Right: Eucalyptust rees lined the corner of Gower Street and MelroseAvenue, ca.1900

The eucalyptus had somewhat of a better run in Los Angeles, remaining a valued part of the treescape until the second half of the 20th century, long after the pepper trees had faded from glory. Imported from Australia and cultivated in large quantities in the decades after the California Gold Rush, eucalyptus trees were touted as the solution to ‘the timber problem of the nation’, providing valuable hardwood resources to take the place of the oaks and redwoods that are native to the California region. The eucalyptus also had several local advocates, the most well-known being thetobacco heir Abbot Kinney, who actively promoted the cultivation and propagation of the species and himself planted eucalyptus groves at his Santa Monica forestry station. Like the pepper trees, their abundance made them cheap and an easy option for street improvements. As late as the 1970s and ’80s, eucalyptus trees were valued in California, taking their place along several major streets and boulevards in Los Angeles and across the region.

The status of the eucalyptus as a naturalised species would however soon be challenged. Conservation biologists in the 1980s began to advocate that the habitats be returned to their pre-settlement conditions, framing the eucalyptus as an outsider that did not belong in the California landscape. A lethal fire in the eucalyptus groves in the Berkeley Hills firestorm of 1991 and further insect infestations in Southern California due to container shipping finally struck a heavy blow to the reputation of the species. However, even to this day, there is passionate resistance from communities that advocate protecting and leaving the eucalyptus in place as a valuable tree that has successfully naturalised to the region. Naysayers are often accused of ‘biological nativism’ or ‘botanical xenophobia’ for casting the eucalyptus as an alien invader. While several thousand eucalyptus trees can still be found in Los Angeles, they have nevertheless been dwarfed by the palms as the arboreal highlight of the City of Angels.

Naysayers are often accused of ‘biological nativism’ or ‘botanical xenophobia’ for casting the eucalyptus as an alien invader

The bold and the beautiful: Moreton Bay figs and jacarandas

Two other examples of immigrant trees that stand out for their impact on the visual landscape of Los Angeles are the Moreton Bay fig, native to Australia, and the jacarandas that originally hail from the South Americas.

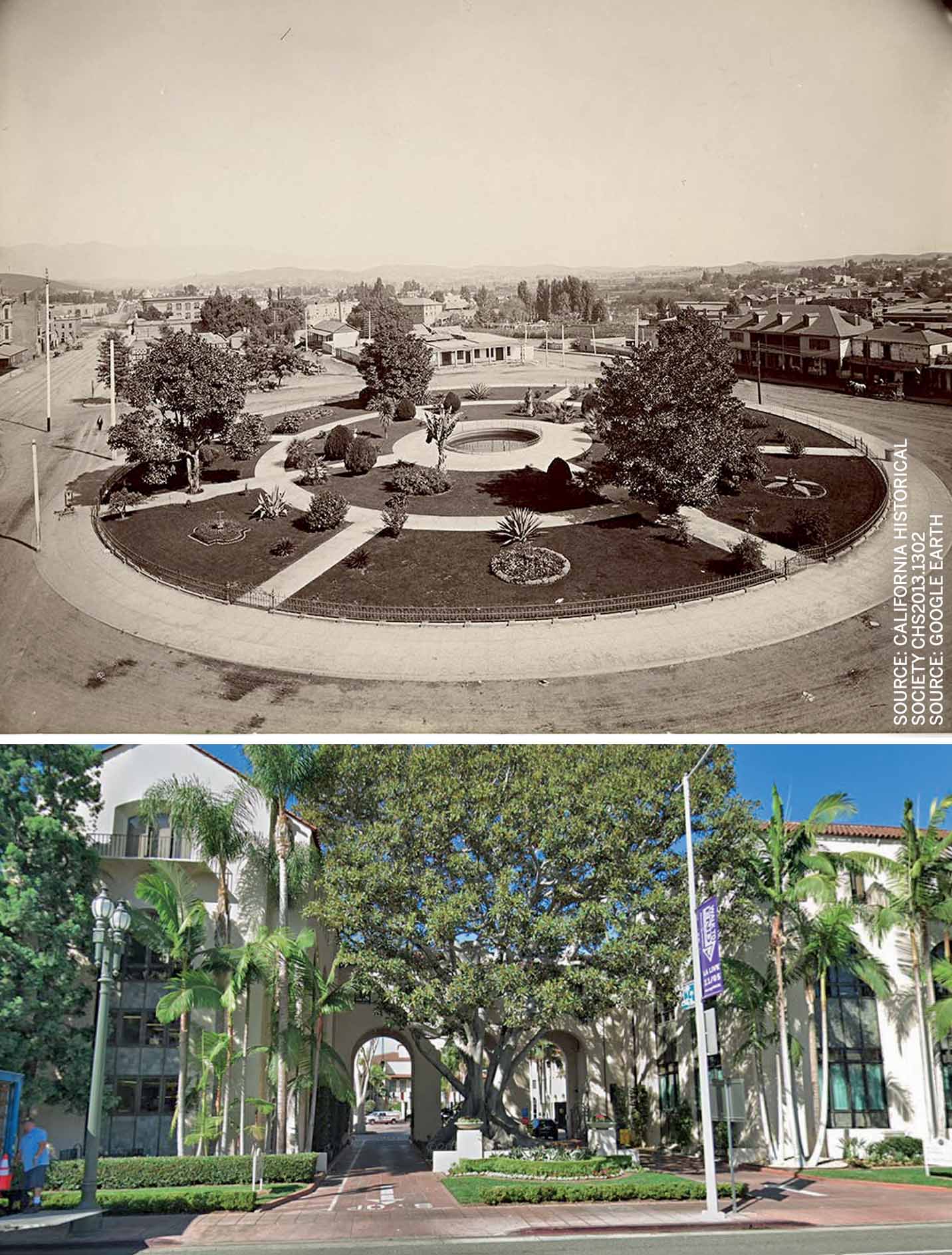

The Moreton Bay fig is unique in that while it never really gained the widespread status of a street tree in Los Angeles – there are only about 900 of them in the city today – its mammoth form makes it a spectacular shade tree and an imposing visual element that never ceases to impress. This is a tree that can be found at historic locations within the city; four of them were planted in 1875 by Elijah Hook Workman around Los Angeles Plaza at the heart of the city’s origins where they provide shade to this day and several more line Vermont Avenue on the approach to Griffith Park, one of the largest urban parks in Los Angeles. These latter group of trees are themselves designated and protected as historic-cultural monuments by the City.

The Moreton Bay fig is another example of a thirsty species. Native to a rainforest climate, it’s unlikely it would have survived without human intervention to provide the water needed to grow and thrive. Various tales account for its presence in Los Angeles. It is believed that at least some of the saplings were mistaken for Magnolias when originally planted along a residential street in Santa Monica. The residents of the street, captivated by the unique form and visual quality of the trees have fought to protect and keep them, despite their intensive watering needs. Another story goes that when the saplings arrived in LA in 1875, they were planted without any knowledge or imagination for how big they could grow to – over 75 feet in height and over a 100 feet in spread. In addition to its size, the Moreton Bay fig also puts out aerial roots that harden and create an imposing sight of thick coiling networks on the ground. Today, the surviving examples of this species are celebrated as unique, imposing elements in the landscape and a prized piece of arboreal heritage in Southern California.

Bottom: Moreton Bay fig framed by young palms at the Los Angeles Auto Club on Figueroa Street

Middle: Jacaranda in bloom

Bottom : Victorians andJacarandas

The jacarandas are also a visual treat in that they produce beautiful canopies and carpets of flowers when they bloom each year. The ubiquitous blue jacaranda with its purple flowers creates a fairy-tale atmosphere in the city for a few brief weeks each spring. Another immigrant tree with over a century of association with the landscape of Los Angeles, the jacaranda is believed to have been brought to Southern California from Brazil around the time of the Gold Rush. However, it wasn’t until the early 20th century that it became predominant in the LA landscape. In his 1916 book, Finding the Worth While in California, naturalist Charles Francis Saunders speaks of the ‘cloud of blue’ of the jacaranda trees that made driving in the spring from Los Angeles to Riverside ‘nothing short of entrancing’.

In addition to its burst of bright colour, the added appeal of the jacaranda is its temporality. In a landscape that barely registers the changing seasons, the blue-flowering jacaranda is a reminder of the passage of time, transforming the streets of Los Angeles for a short period of time each year. However, the tree does come with its challenges. The flowers create a sticky mess on sidewalks and pavements when they are shed from the tree, a condition that is often a source of complaint for indignant homeowners. The flowers also attract aphids that feast on them in large quantities and their excrement is another source of nuisance that often draws hate towards the jacarandas. Despite these challenges, the visual appeal and drought tolerant characteristics of the jacaranda make it a promising option and it will likely be around for some time to come, spreading joy (and some angst) each spring.

The landscape of the future

The immigrant trees of Los Angeles stand testimony to the city’s centuries-long relationship with the exotic and the beautiful. As the city continues to grow and change however, the priorities for the landscape of the future are in transition as well. Increasingly, Angelenos look to native, hardy species that are practical and water efficient in the lengthy droughts of the region. For trees, the functional needs for shade to reduce urban heat islands and purifying the air have become as important as an exotic quality and visual appeal, so much so that the City’s Parks and Recreation department have confirmed they will be substituting dying palms with other utilitarian species rather than replanting them across Los Angeles for their iconic value. With these changing priorities playing out, the urban landscape of Los Angeles will likely look very different a hundred years from now. In the meantime, however, many of LA’s immigrant trees have left their mark on the city’s history.

Comments (0)