Cantonment towns across India are a legacy of the British Raj. Derived from the French word ‘canton’ meaning a corner or district, it describes a place where units of the army are encamped permanently. During the British occupation of India, the cantonments were either set up in the garrisons of the erstwhile princely states or new ones were established in strategic locations, where the British-Indian army deployed their units. In most cases, they were founded in the cool mountains, which gave the British officers a respite from the heat of the Indian summer. These locations were invariably very scenic and just like the many ‘hill stations’, which were developed for the summer sojourns of the sahibs, the cantonment towns perched on the picturesque mountain ranges remain a pleasant travel destination.

Pachmarhi is a cantonment town located in the Satpura range in the Hoshangabad district of the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. Captain James Forsyth discovered the plateau in 1857 as he led his troops towards Jhansi. It soon became a sanatorium for the British troops stationed in Central India. The cantonment was established in 1862 and it became the summer capital of the Central provinces.

Pachmarhi gets its name from the five caves found there. Though these caves are Buddhist in nature, legend believes them to be built and dwelt in by the five Pandava princes of the Mahabharata during their period of exile. Before the arrival of the British, Pachmarhi was a part of the Gond kingdom and was moderately populated. Today, most of the town comes under the administration of the Pachmarhi Cantonment Board serving the Indian Army and has a population of just over 10,000, most of whom are associated with the installations of the army.

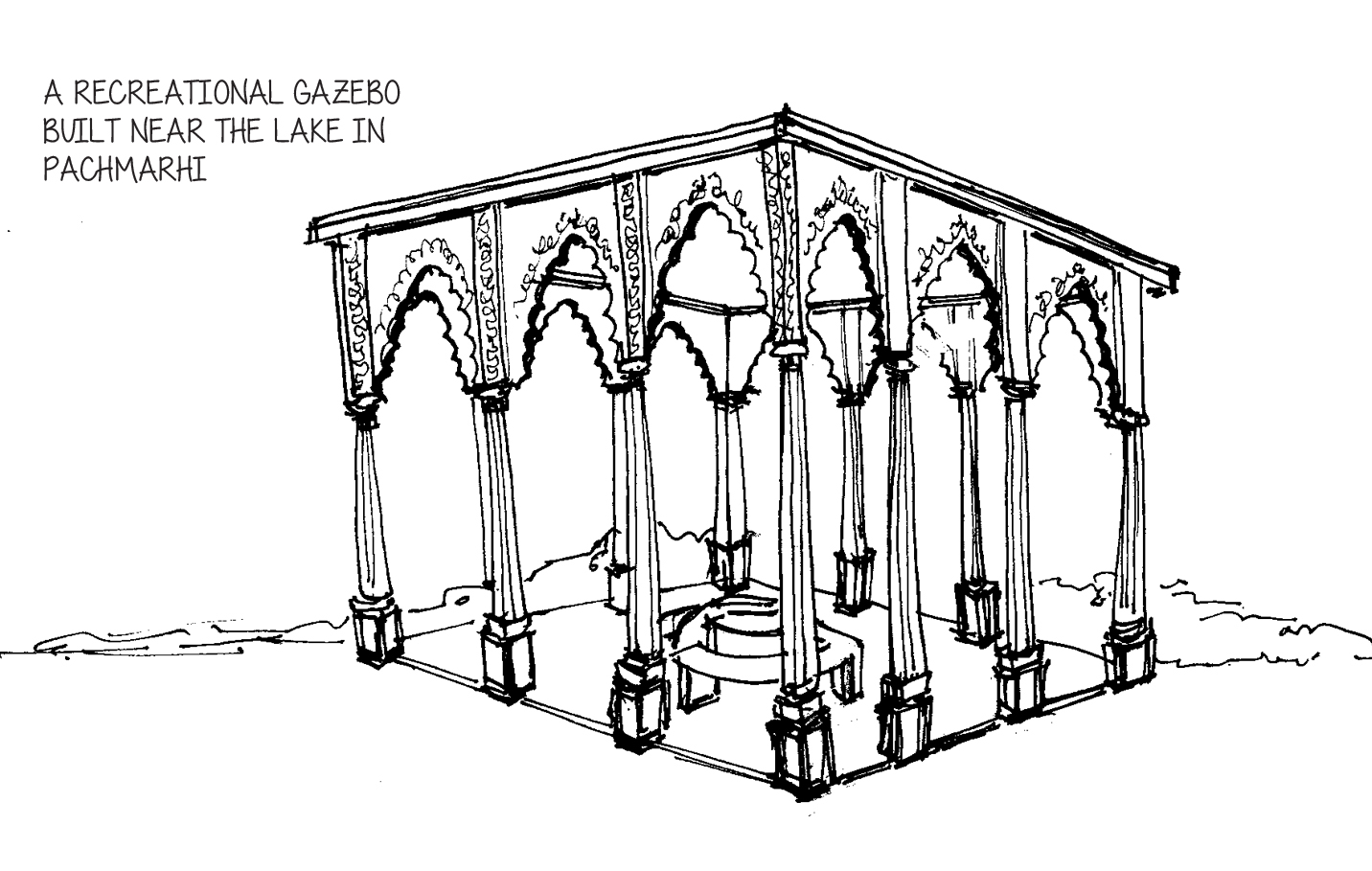

The Cantonment Boards set up under the Cantonment Act of 1924 provide the municipal administration for all these areas, which includes road works, sanitation, electrification and also primary education and health care. Set up and maintained under a military discipline, these areas are always better kept than most other municipal areas in the country. Clean roads, whitewashed curbs, tall trees and manicured gardens in public spaces have been the hallmark of cantonment towns. This along with the natural beauty of the place and a friendly climate makes them desirable locations within the country.

The wilderness around Pachmarhi is a haven of flora and fauna

The wilderness around Pachmarhi is a haven of flora and fauna. Wildlife includes the tiger, leopard, the chital deer, the bison and the flying squirrels, besides many others. Home to rare varieties of plants, UNESCO has added Pachmarhi to its list of biosphere reserves. Apart from a variety of fruits like the mango and the jamun and locally known fruit like khatua and chunna, the forests around the town are rich with medicinal plants. It is also a very rich resource of protected teak.

An Englishman’s vision more than 150 years ago opened this beauty to the world

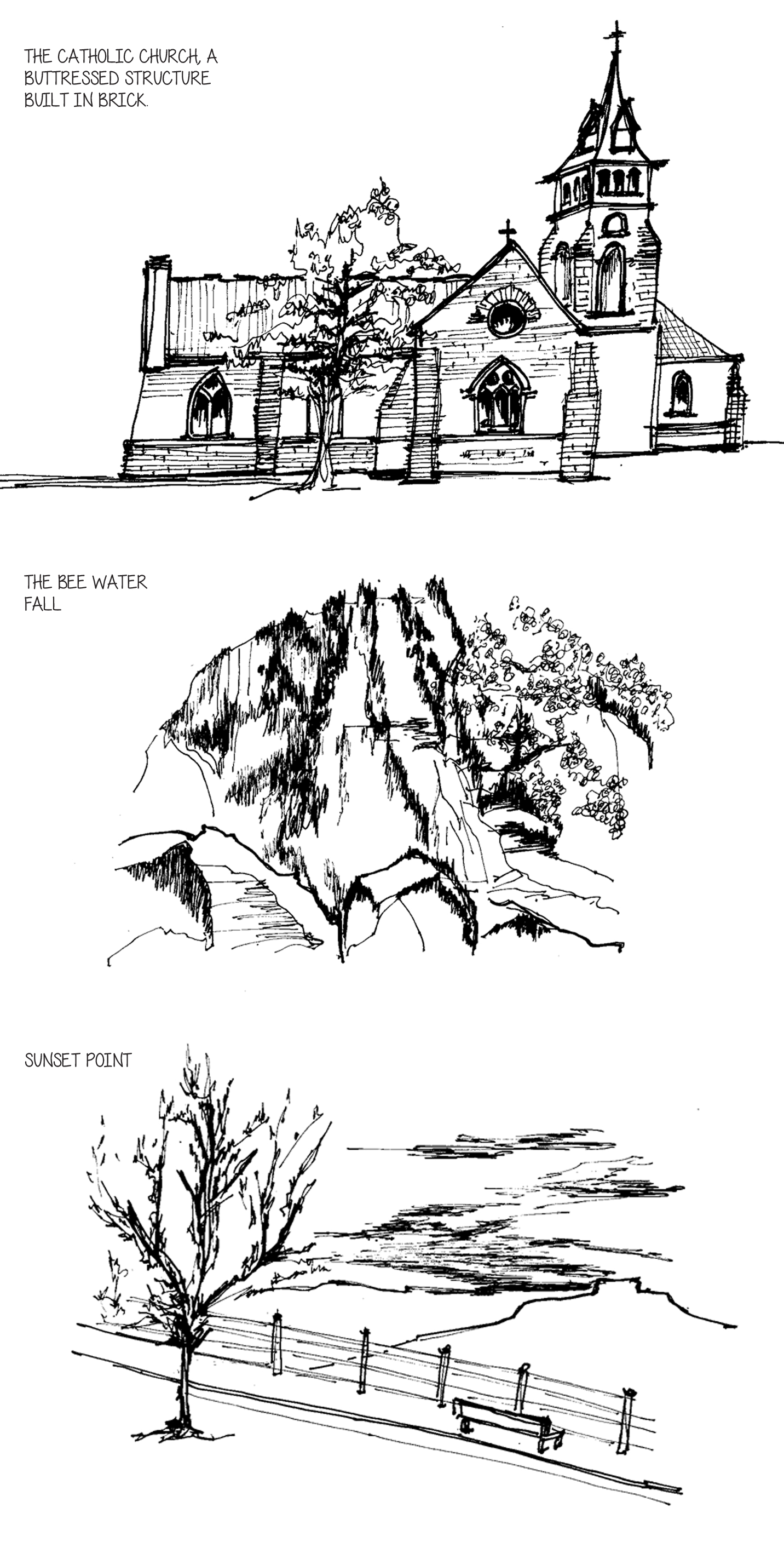

The forestry, amidst the contours of the Satpuras, makes Pachmarhi a trekker’s delight. It is difficult to list out walking trails, but vantage spots, waterfalls, caves and age old shrines can lead one to exciting experiences in the lap of nature. Tourism being the mainstay of its economy, many spots have been identified and are popular today. Besides, for the adventurous spirit, there is a lot one can discover.

Dhoopgarh is the highest point on the range and provides a magnificent view of the Satpuras. Chauragarh, the second highest point, is the place to climb up to early in the morning if you want to catch a breathtaking sunrise. Then there’s the Chauragarh Fort built by one of the Gond kings and is a pilgrimage spot for Shiva worshippers. The ecosystem is blessed with many waterfalls and fresh water lakes like Panarpani. The Rajat Prapat waterfall in a single drop of 350 feet is a wonder of nature and is listed as the 30th tallest in India.

The Bee Falls gets its name from the humming sound it makes as the water cascades down. The Mahadeo Hills have an impressive statue of Shiva and the lingas. The Jata Shankar caves are stalagmite caves with natural formations of the Sheshnag and Shivlinga and is gradually becoming popular as a holy site. Handi Koh is a gorge with 300 feet-tall cliffs offering magnificent views. The forest also holds cave paintings dating back 10,000 years.

Pachmarhi is a heady mix of legend, history, belief and nature’s bounty. An Englishman’s vision more than 150 years ago opened this beauty to the world. In many ways, due to a highly regulated development plan, time has stood still here. And that indeed has taken care of this ‘queen of Satpura’.

All DRAWINGS: Pritha Sardessai

Comments (0)