The oldest city of the Netherlands, originating in Roman times, is currently undergoing an enormous transformation due to the climate change in Western Europe. Situated on the edge of the German-Dutch border, on the river Waal, Nijmegen was part of the frontline and was bombed and destroyed during the Second World War. Due to the climate change, rivers must process increasingly larger amounts of water and the city has always been at risk of flooding. In 1993 and 1995 things almost went terribly wrong when the dykes were on the verge of failing and a disaster was at hand. A quarter of a million people had to be evacuated from their homes. This was a wake-up call for the Dutch who were already engaged in executing the huge Delta programme.

The Dutch tradition of water management goes back to the Middle Ages. Right from then, polders, dykes and mills were constructed to reclaim land from seas and rivers. In the 1950s, Dutch engineers built the Delta Works, a revolutionary series of barrages along the North Sea Coast.

Ever since, thinking has evolved. In response to the climate change, Dutch engineers have developed strategies that go beyond just trying to keep the water out. The new goal or way of work is to co-operate with water instead of just defending ourselves from it.

Room for the River Waal

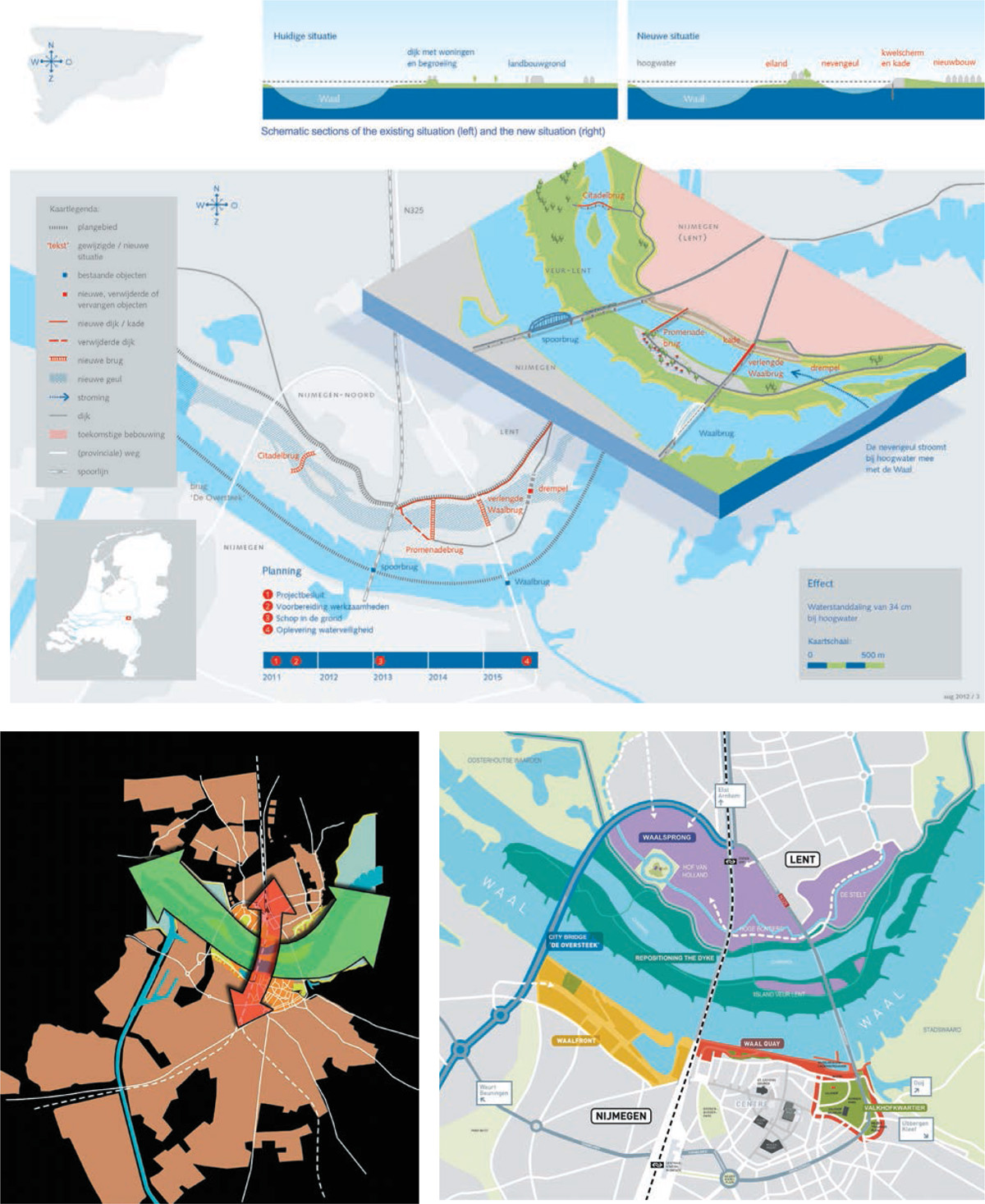

The higher we build the dykes, the greater the volume of water during floods and higher the risk for people who live behind the dyke. Instead of raising the dykes, which we used to do, we look for solutions in river-widening to be the future of the Dutch water issues. As a part of this so-called Dutch approach, Room for the River, was born. The implementation restores the river’s natural flood plain in places where it is least harmful in order to protect areas that need to be defended. A series of 34 measures, costing 2.3 billion euro, will lower and broaden our flood plain. Provinces, municipalities, water boards and the National Government are cooperating in the implementation of the Room for the River Programme.

Room for the River Waal, Nijmegen, is one of these projects. The River Waal bends sharply near the city and moreover, it narrows itself in the form of a bottleneck. To create more space for the river, the dyke has been moved 350 meters inland and an ancillary channel constructed in the new flood plain. This will create an island in the Waal and also a unique urban river park in the heart of Nijmegen with room for housing, recreational activities, culture, water and nature.

A new island

The island will form a new part of the city: Higher areas of it may contain apartment buildings; other lower-lying sections will be developed into parks and beaches. During flood periods, the lower reaches of the island will simply be engulfed by water. The new embankments in this lower area will be a place where people can relax and enjoy views of the historic city center and it will encourage daily awareness of the ever-changing water level.

When the plan was presented, the reaction in the community was that of anger. To the Dutch, dams and dykes mean security. Allowing the water in went against centuries of ingrained thinking.

But after a session between city planners, community groups, the national ministry in charge of infrastructure and the region’s water board, the town as a whole came around to the idea that because the world had changed, water management had to change as well.

When the final design was unveiled at a community meeting in 2009, it included both expansive recreational areas and a level of security from water that promised to make the city attractive to new companies. Those who were initially most resistant to the project — residents of Lent, the community that was to be trimmed to make way for the river — started to applaud. ‘The Ovation of Lent,’ as the local newspaper called it, signaled what planners had been working toward: the acceptance of climate change as a way of life and the dawn of a 21st-century approach to living with nature.

First, it was necessary to realize a second bridge over the river before the start of the construction of the new channel could commence. This bridge was necessary to accommodate increasing mobility between the newly-planned urban development on the north bank of the river and the existing city on the south bank. But above all, the realization of this new river crossing guaranteed the accessibility of the city of Nijmegen in the period when the secondary channel was dug out. The new city bridge was a challenging assignment.

Nijmegen already had an iconic bridge, the Waal Bridge of 1936, whose imposing arch structure had led the Dutch government to declare it a historic monument.

Nijmegen’s city council had called for a City Bridge in the design assignment. The impressive result is a large single-arch bridge with monumental tile-covered approach viaducts. The designers of the city bridge – Ney & Poulissen – have designed a bridge that blends into the urban and natural landscape.

Both in the procurement of the new city- bridge and in the procurement of the Room for the River project, the city council set ambitions for spatial quality. These specified criteria for the selection of the implementing contractor to focus on quality, integral urban design, respect for the river landscape, functionality and sustainability.

After completion of the city bridge, it was possible to start with the excavation of the side channel and the construction of three other bridges and a new quay.

Bridging

To connect both parts of the city and to make the new island accessible, three bridges were needed. The city council called for a design competition aiming to select three different architectural bridges. The biggest of them is the extended Waal Bridge.

To construct the ancillary channel, the old Waal Bridge must be extended. The new part of the bridge is to be a modern design with beautifully shaped concrete arches. The Lentloper Bridge connects the island with the new quay. This bridge can be considered as a continuation of the city across the water; a promenade with lovely views. The bridge is accessible for automobiles, cyclists and pedestrians. The third bridge, the Zalige Bridge, links the western part of the island to the future urban district. The bridge is intended for cyclists and pedestrians. At high tide, the bridge will stand like a sculpture in the water. The bridge is designed as a winding road in the natural landscape.

|  |

Living with nature

The quay is the new waterfront on the north bank of the river with urban activities on and around the ancillary channel. This quay is directly linked to the two main bridges of Nijmegen and is made up of different levels, which are connected by steps and slopes. The central part of the quay is designed as a theatre and offers space for outdoor concerts or festivals. The quay has been constructed as a paved sloping surface that gradually disappears into the water. This creates an optimal experience of different water levels occurring in time. The quay offers possibilities to enjoy a stroll, for cycling, sitting outdoors on the terrace and to admire the boats at the landing place.

The starting point of the landscape design is the natural processes of the River Waal. Because space is given to natural processes, the former natural landscape with side channels and sandy ridges returns to the floodplain. The fertility of the area and the continuous supply of seeds and organisms from the river provide a rapid revival of river-bound nature.

Close to home, the inhabitants of the city can easily enjoy this wild nature. Typical for the site are the many traces of river life. Historically, this area has often been a battleground: bunkers and traces of the fortifications of Knotsenburg are witnesses thereof. In order to respect cultural history, significant old structures are integrated in the plans. The old landing place of the ferries and an old fortress are reconstructed in the plan and various historical objects have a prominent place in the new landscape.

Urban development

Now that the public works, consisting of bridges, quays and the secondary channel have reached their completion, the city is already busy making plans for the adjacent urban areas. For the urban development of the areas around the Waal, an organic and flexible strategy will be chosen.

Temporary activities in certain areas can be used as a prelude to a permanent programme. The former Honig Factory is a striking example of place-making: temporary use trendsetting for the final development. The distinctive complex is located in the west of the city and is easily accessible. It provides food and drinks, sports, shopping, music and much more. For the city island various similar ideas are currently underway. For example, a water sports center for students of the rowing club. On the eastern Waalkade – on the border of city and nature – a new museum, The Bastei, will be realized. This cultural and historical center will be built on the foundations of former old fortifications and will showcase the history of living with the river.

Developments around the Waal demonstrate a new way of thinking in which design strategies are combined to create a climate-resilient future for the city. Nijmegen has established a combination of climate resilience, future sustainability and spatial quality. Besides flood protection, the plan creates opportunities for housing, recreation, culture and nature. Nijmegen has integrated the necessary river widening of the Waal into urban development. Nijmegen transforms from a city ‘next to the River Waal’ to a city that embraces the river. An intensive, substantive cooperation between designers, researchers, citizens and governmental bodies has led to a city that has physical, social and ecological resilience. The project demonstrates a paradigm shift in the way we deal with climate change. The result is an impressive new identity for the city of Nijmegen on the Waal.

Comments (0)