Housing, and the need to create shelter, is as old as mankind itself. Long before the advent of professional specializations and the beginnings of the profession that later came to be called Architecture, human settlements were being built in different parts of the world by ‘indigenous’ people.

In 1964, this came under renewed attention and scrutiny because of a special exhibition on this topic at MOMA (Museum of Modern Art), New York, and the publication of the book Architecture Without Architects by Bernard Rudofsky.

Rudofsky described architecture without architects as: “Vernacular architecture does not go through fashion cycles. It is nearly immutable, indeed unimprovable, since it serves its purpose to perfection. As a rule,the origin of indigenous building forms and construction methods is lost in the distant past.

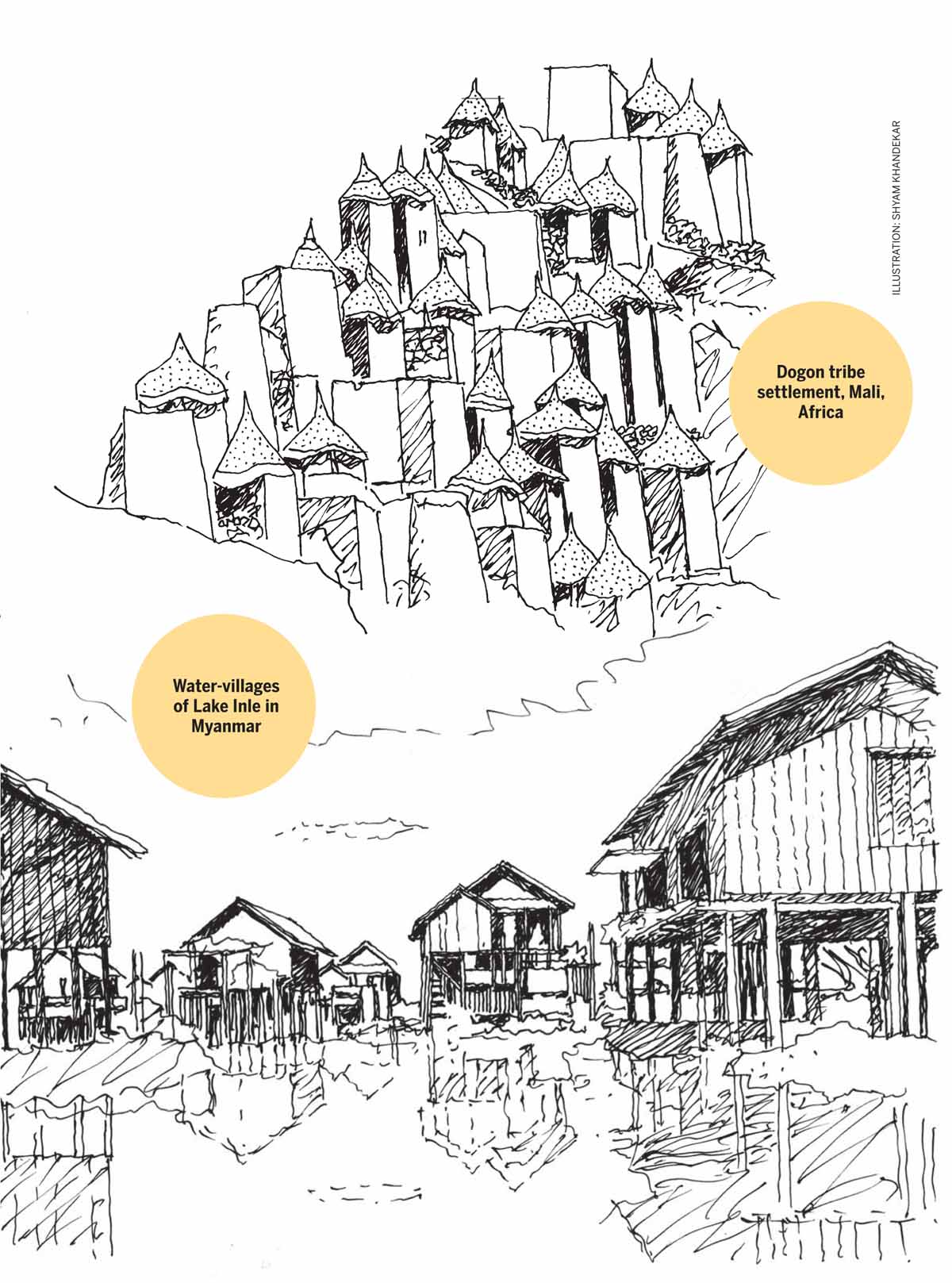

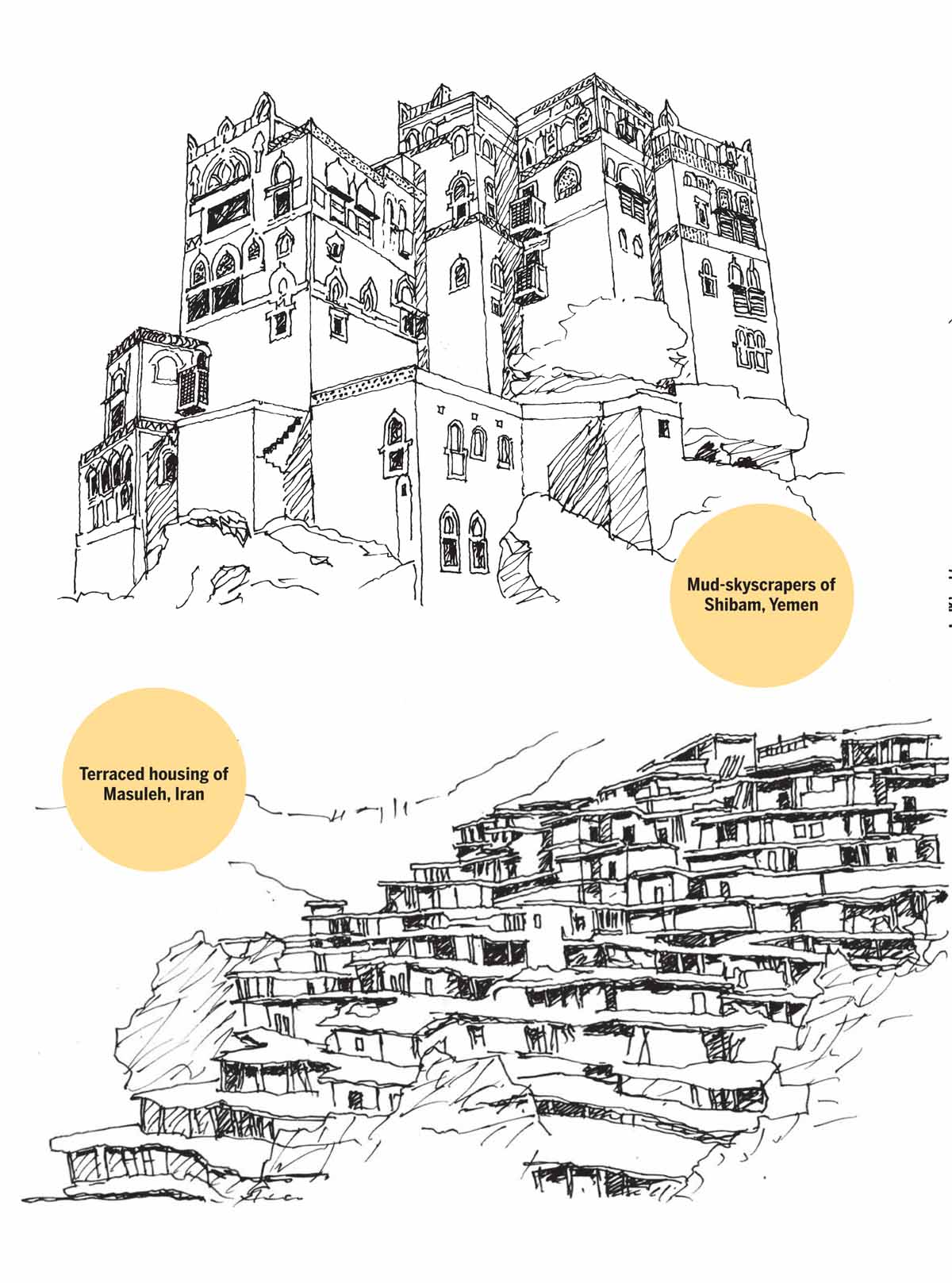

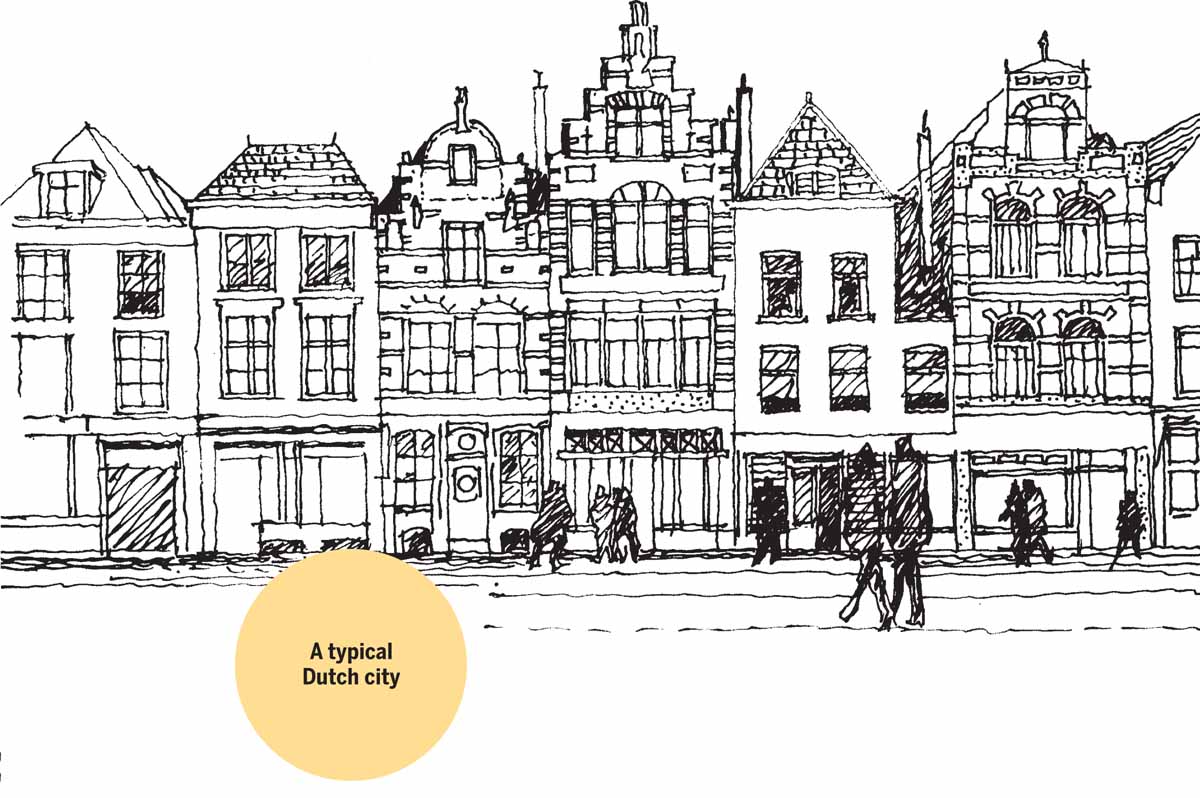

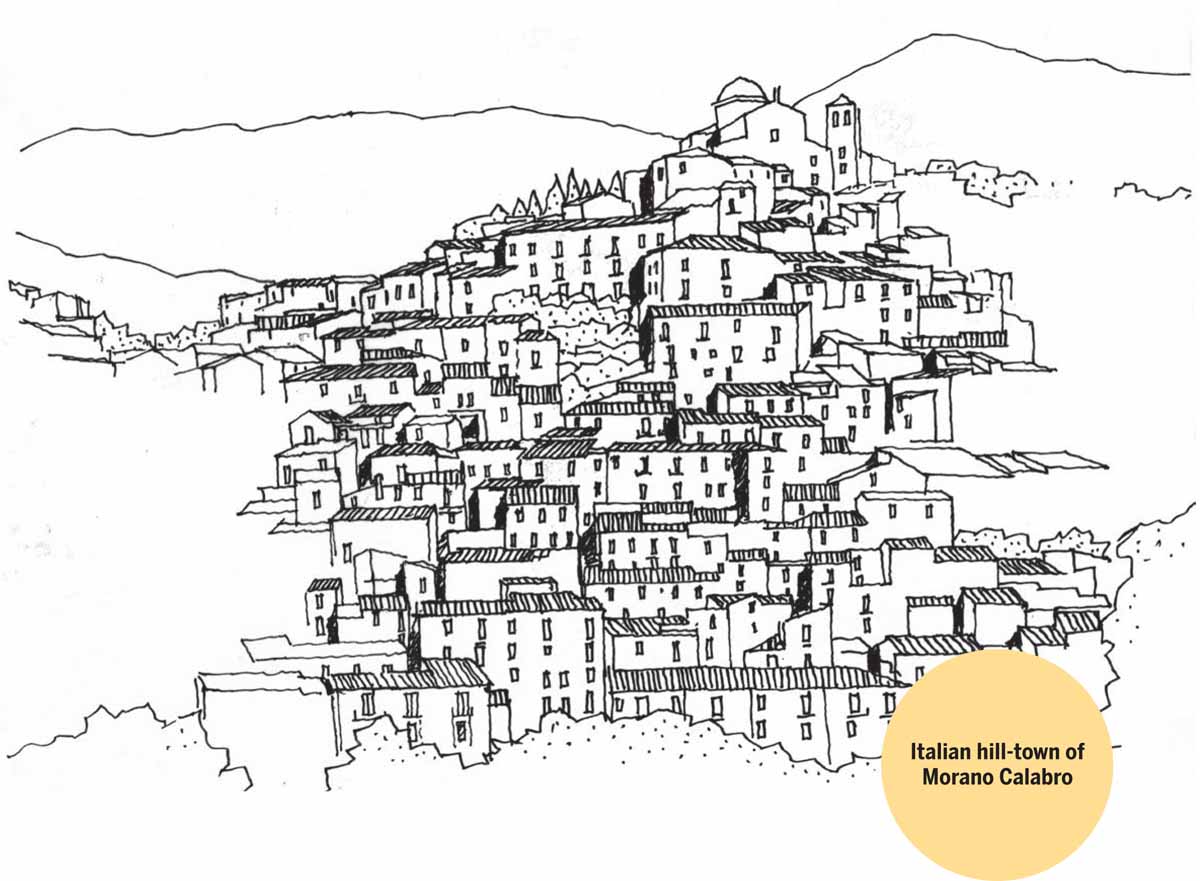

The sketches on the pages of this article of housing of the Dogon tribe in Mali, Africa, the mud-skyscrapers of Shibam, Yemen, the terraced housing of Masuleh, Iran, the housing in the water-villages of Lake Inle in Myanmar, the more recent Italian hill-town of Morano Calabro and the housing from a typical Dutch city, represent just a few examples of what we could truly call ‘housing without architects.’

Each of these examples is testimony to the wisdom and creativity of the different people who, through a process of centuries of collective knowledge and improvements, perfected a design that was absolutely suited to their environment.

While the final design in each context is a unique answer to the specific climatic, social and economic situations of that specific society and while each design is therefore unique, they all have the following traits in common, which in each example can be to a different degree. The traits are:

A. Suitability to the specific climatic and physical conditions.

B. Sustainable through their usage of local (and often renewable) building materials.

C. Community-based and involving participatory building processes.

D. Perfection based on generations of wisdom.

Finally, each of them allowed an incremental and organic pattern of growth of the settlement in which the housing units were added as the necessity arose. Each of them incorporates a pattern of repetition of ideal or nearly ideal units whereby the size of the settlement grew organically to respond to the growth of the population and its needs. Visually they resemble biological cells, which have proliferated under the right circumstances.

In a period of unprecedented migration to cities and development of new cities and planning techniques, such unique places are in great danger of obliteration. Yet we must realise that such communities represent a wealth of knowledge, which even today holds water. Their future is as much part of the global urbanization story as our newly-designed and professionally planned cities.

Comments (0)