Apart from our homes and workplaces, one could argue that the place we spend the most amount of time is on streets – whether travelling to work and back home again, going to the store, visiting friends, taking our kids to school, venturing out to eat or going to see a movie. Yet, many of the streets we use to get to these places are among the least inspiring, least memorable parts of our cities.

One of the primary reasons that many streets are this way is that city street design standards and building design regulations (zoning) are completely separate and unrelated documents managed by different city departments. Street design standards, typically administered by public works or engineering departments, focus on vehicular movement and throughput, while zoning regulations, typically administered by planning departments, focus on building setbacks, height and land use. This separation makes sense since streets are located within the public right-of-way and are typically built and maintained by the municipal authority, whereas buildings are located on private property and are typically built and maintained by a developer or land owner. Accordingly, city departments generally approach the relationship between street standards and building design regulations according to purely practical considerations: the amount of traffic a particular land use will generate or how developer impact fees will fund a street improvement. The formal design relationship between the two, however, is often ignored.

Inspiring and memorable streets, however, cannot be designed in such isolation. Without buildings informing the design of the street – and vice versa – good street design is virtually impossible. City design standards, then, need to regulate both the design of the street and the design of the buildings that face the street. Essential ingredients of memorable streets include: the buildings that line them, the sidewalk and how it relates to the vehicular lanes on one side and buildings on the other, and the streetscape, especially street trees.

|

Buildings

Buildings are the most important character-defining component of urban streets. Narrow streets are so perceived not solely because the vehicular lanes are narrow but because the buildings are located close to the roadway. The narrowness of the street is even more pronounced if the height of these buildings is greater than the width of the street. Grand streets are grand because they are wide and are lined by majestic buildings and streetscapes. An important monument, civic space or building often occupies the terminus of these streets. In both cases, the buildings define the form of the street.

But the mere presence of buildings is not enough to make a street memorable. The design of the buildings themselves – particularly how they relate to the street – is just as important. The most memorable streets – whether a quiet, single-family neighbourhood street, an active small town commercial main street or a bustling, mixed-use downtown avenue – are lined with buildings that engage and activate the street. These streets are appealing because the buildings fronting them have ample street-facing windows, interesting facade articulation and are entered directly from the street through human-scaled frontage types.

Windows impart a human face to buildings and provide ‘eyes on the street’ – passive security whereby residents, office workers or retail patrons provide informal surveillance of activities that are occurring on the street. Facade articulation – including varied massing, interesting material treatments and the use of architectural elements such as balconies, bay windows and awnings – modulate and embellish what would otherwise be flat and formless building facades.

Inspiring and memorable streets cannot be designed in isolation

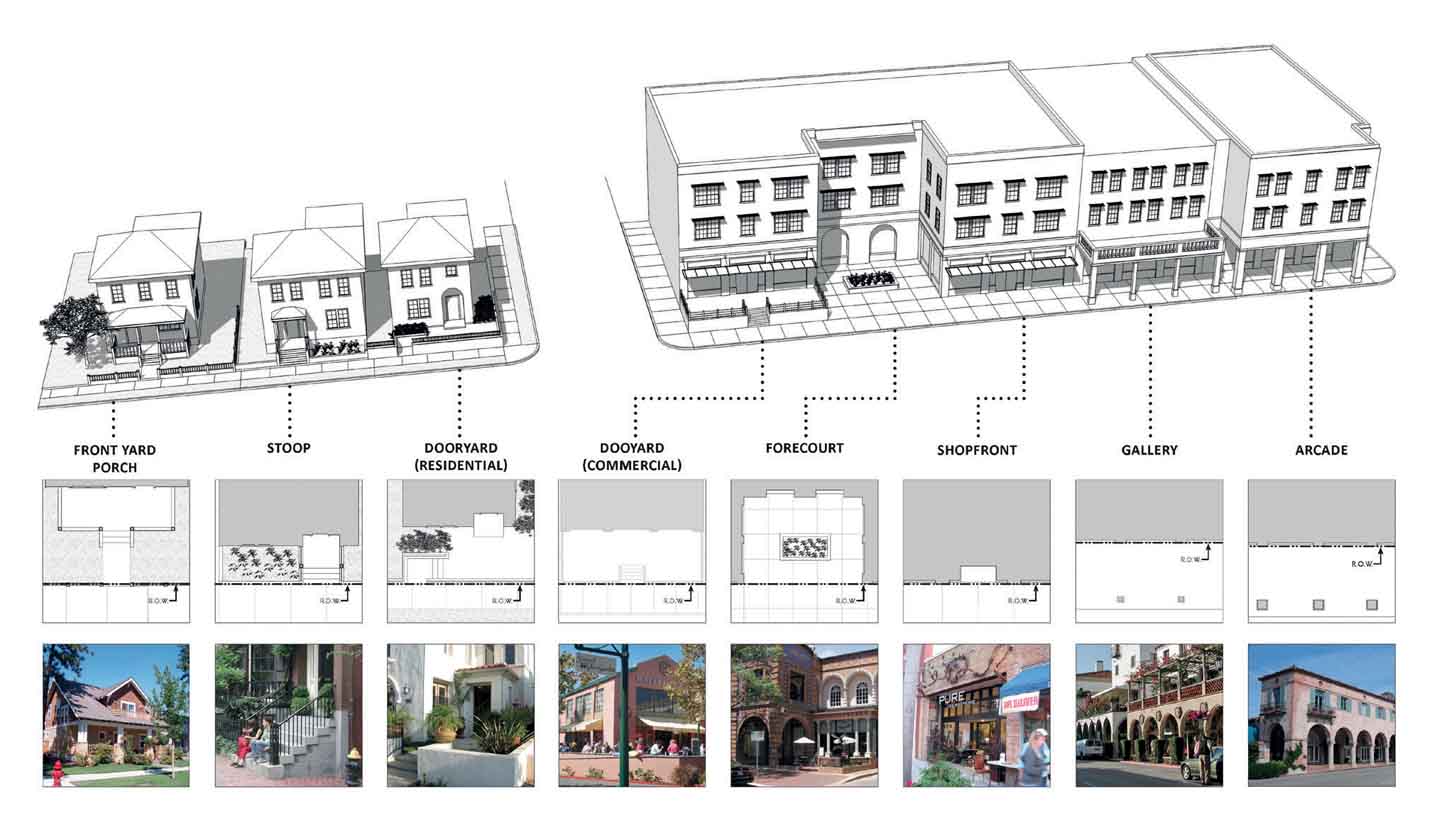

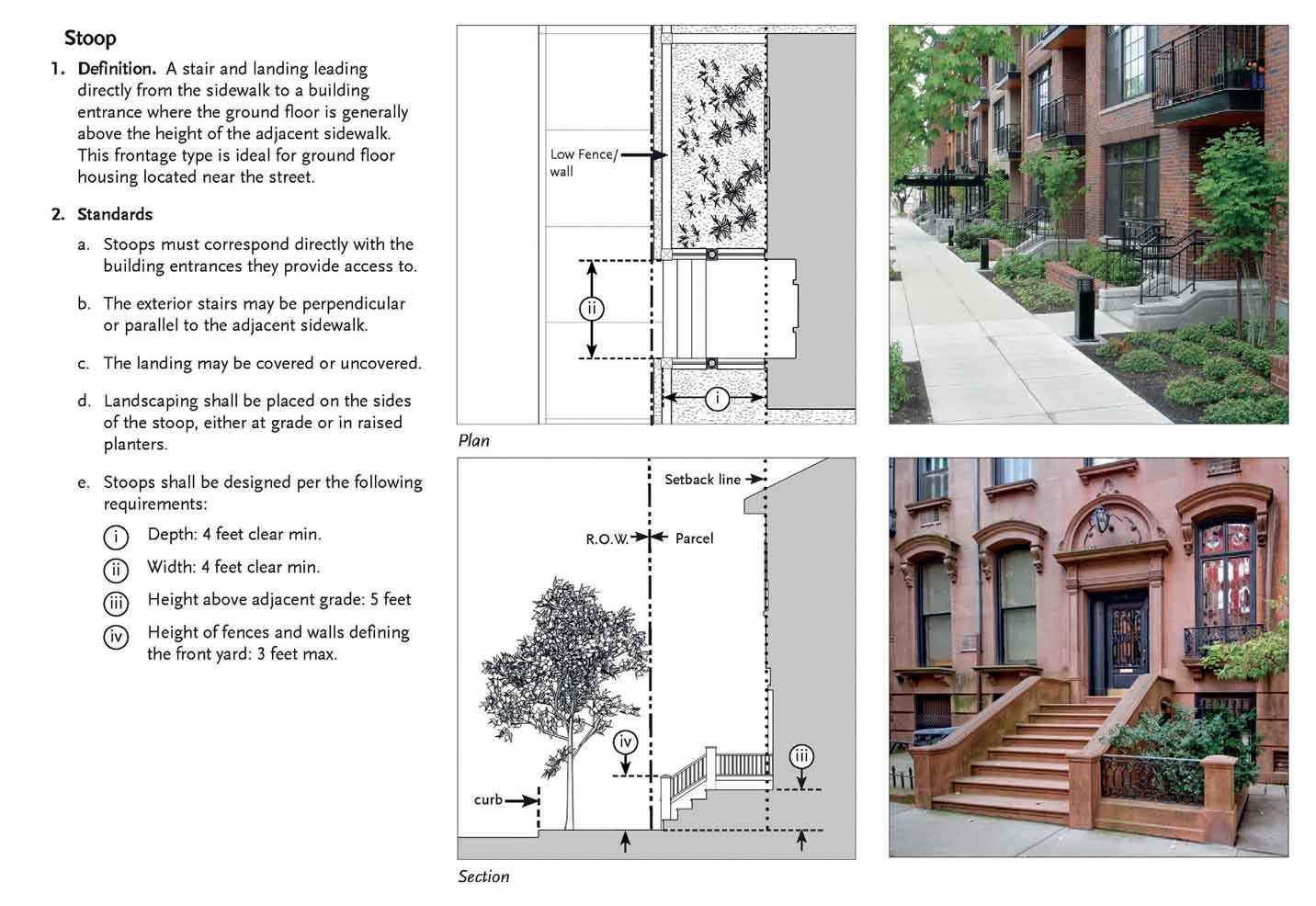

Frontage types are how buildings are entered (see Figure 1). They provide a transition between the public world of the street and the private realm of the home, office or store, moderate the scale of a building to the street and to adjacent buildings (for instance, the apparent scale of a two-storeyed building next to a one-storeyed building can be reduced with the introduction of a one-storey porch) and add a human-scale to buildings. Frontage types for residential buildings include porches, stoops, dooryards (patios or terraces enclosed by a low wall or hedge), verandahs and lobby entrances. Retail and commercial frontage types include shopfronts, dooryards, arcades and galleries. Arcades and galleries – typically used in tandem with shopfronts – provide shade, protection from inclement weather and reduce glare on shopfront windows. Frontage types and their associated street entries also activate the street. Stores accessed directly through a shopfront from a sidewalk rather than a parking lot, for instance, generate pedestrian activity along the street. Porches and stoops provide a comfortable and shady place for residents to relax on warm summer evenings and to socialise with passing neighbours.

Just as important as what faces the street is what does not face the street. Streets with blank walls or parking located between the sidewalk and the building are unattractive and formless. Automobile parking should accordingly be located beneath the building in subterranean garages or behind the building away from the view of the street.

|

Sidewalks

The quality and disposition of the sidewalk are important too. Successful sidewalks are calibrated to the uses and building intensities they serve. Sidewalks along mixed-use streets are wide enough to accommodate people walking down the street, shoppers going in and out of stores and activities such as outdoor dining. Sidewalks in residential neighbourhoods are narrower since foot traffic is less.

The relationship of the sidewalk to the roadway is important, too. Narrow sidewalks located immediately next to the vehicular travel lanes of busy streets create an uncomfortable environment for pedestrians. On-street parking, on the other hand, shelters pedestrians from moving automobiles and provides convenient parking in front of stores, businesses and residences, encouraging pedestrian activity, boosting sales at adjacent stores and restaurants and reducing the amount of required on-site parking. Street trees and landscape between the sidewalk and the roadway also add an additional barrier between moving cars and pedestrians.

|

Streetscape

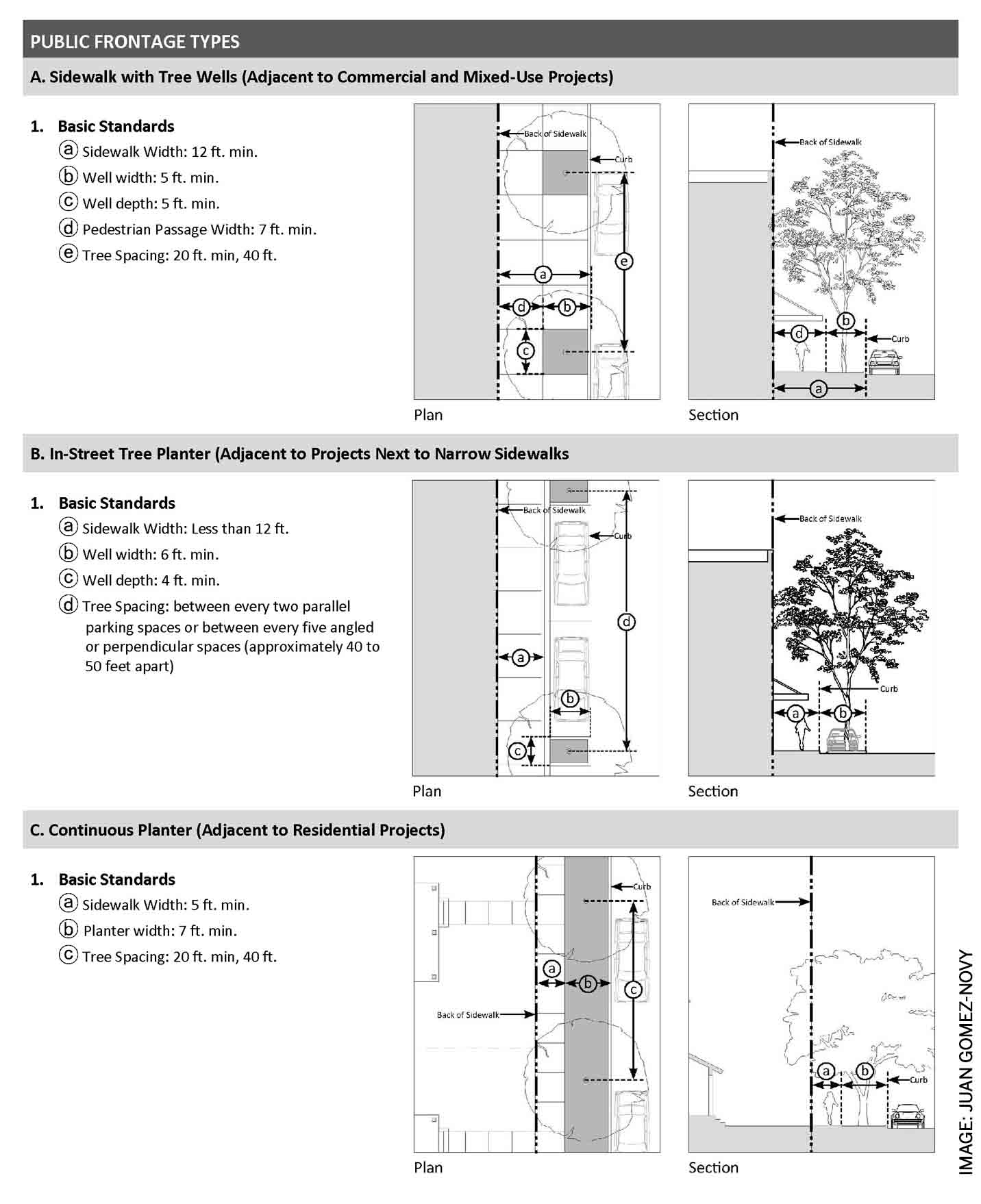

Like buildings, the streetscape contributes to the form and character of the street. How the streetscape is deployed depends on the adjacent building types and uses. Along commercial streets, where sidewalks need to be wider due to greater pedestrian activity, street trees are planted in tree wells. Along residential streets, street trees are planted in continuous planters located between the roadway and the sidewalk.

Street trees can also be used to differentiate one street from another. Planting palm trees on a particular street, for instance, creates a strong, columnar expression along that street. Tall palms, such as Mexican Fan Palms (washingtonia robusta), can make it easy to identify the location of the street from a distance. Trees with vase-shaped canopies along retail streets, on the other hand, shade the sidewalk, while enabling shop signage to be seen beneath the branches of the trees. Street trees can also be selected according to the cardinal orientation of streets. Deciduous trees planted on east-west running streets, for instance, shade buildings during the hot summer months and enable the sun to penetrate during the cool winter months, helping reduce building cooling and heating costs.

|

|

Coding Memorable Streets

Plans and design codes that provide standards for both the design of streets and the buildings that face them are essential for achieving memorable streets. Key elements of these codes include:

1. Street Standards that describe the design of the public right-of-way. Key components include:

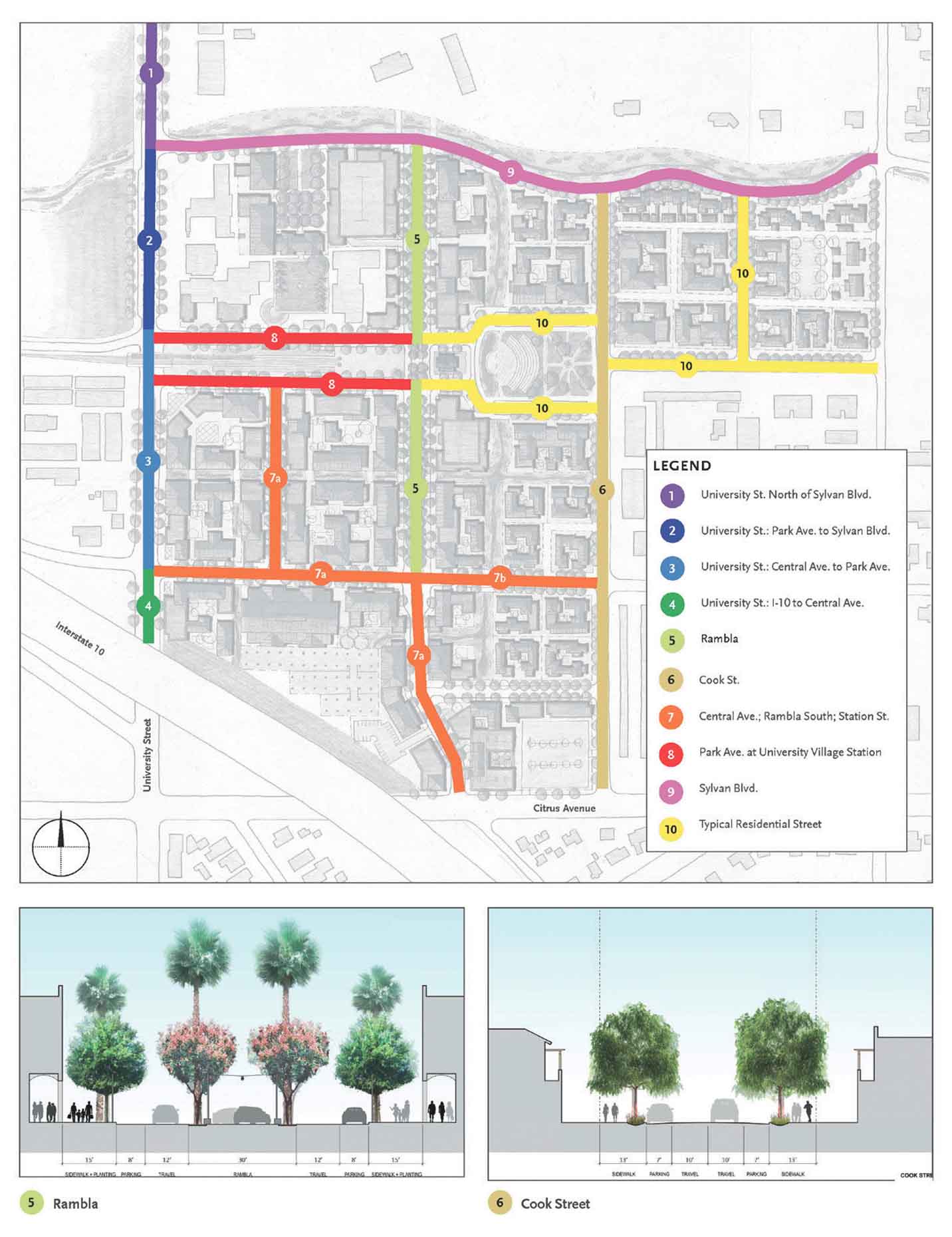

- A street network plan that identifies each street and street sections that detail the design parameters for each particular street, including number and width of vehicular travel lanes, the width of bike lanes, centre medians and sidewalks and street tree location and species (see Figure 2).

- The street tree planter type – continuous or tree wells – depending on the adjacent building types and uses, whether commercial, residential or mixed-use (see Figure 3).

- Criteria for street furniture, street lights, bicycle parking, crosswalks and other elements of street and streetscape design.

2. Building standards that detail how buildings within a given zone relate to the adjacent street. Key components include:

- Building placement standards in terms of setback, height and where parking is located.

- On-site open space, building size, frontage type and access standards that specify how buildings and on-site open spaces relate to and memorable are accessed from the street.

- Detailed frontage type and architectural element standards that specify how deep porches are, how high stoops are, how much of the ground floor retail facades must be glazed, the minimum depth of balconies, the maximum distance bay windows can protrude from the building facade, etc. (see Figure 4).

Taken together, these standards can be used to transform and revitalise existing, underperforming streets (see Figure 5) or to create completely new ones. The outcome is beautiful, active streets where people want to live, work, shop and visit, where shop owners want to refurbish and renovate the facades of their stores, where developers and business owners want to invest and reinvest, and where we will enjoy all that time spent going back and forth on them.

All photos: MOULE & POLYZOIDES

Comments (0)