Leiden 2005. The homes in this district of ‘Oude Kooi’ had sandbags blocking the front doors to stop water from flooding their homes. Once the fire department had pumped out the water, the home owners raised their thresholds to avoid getting caught in future flooding. In some houses the entire ground floor was raised. Due to Climate Change, heavy rains are expected to become more frequent in the future. A permanent solution is vital, but what is it?

Introduction

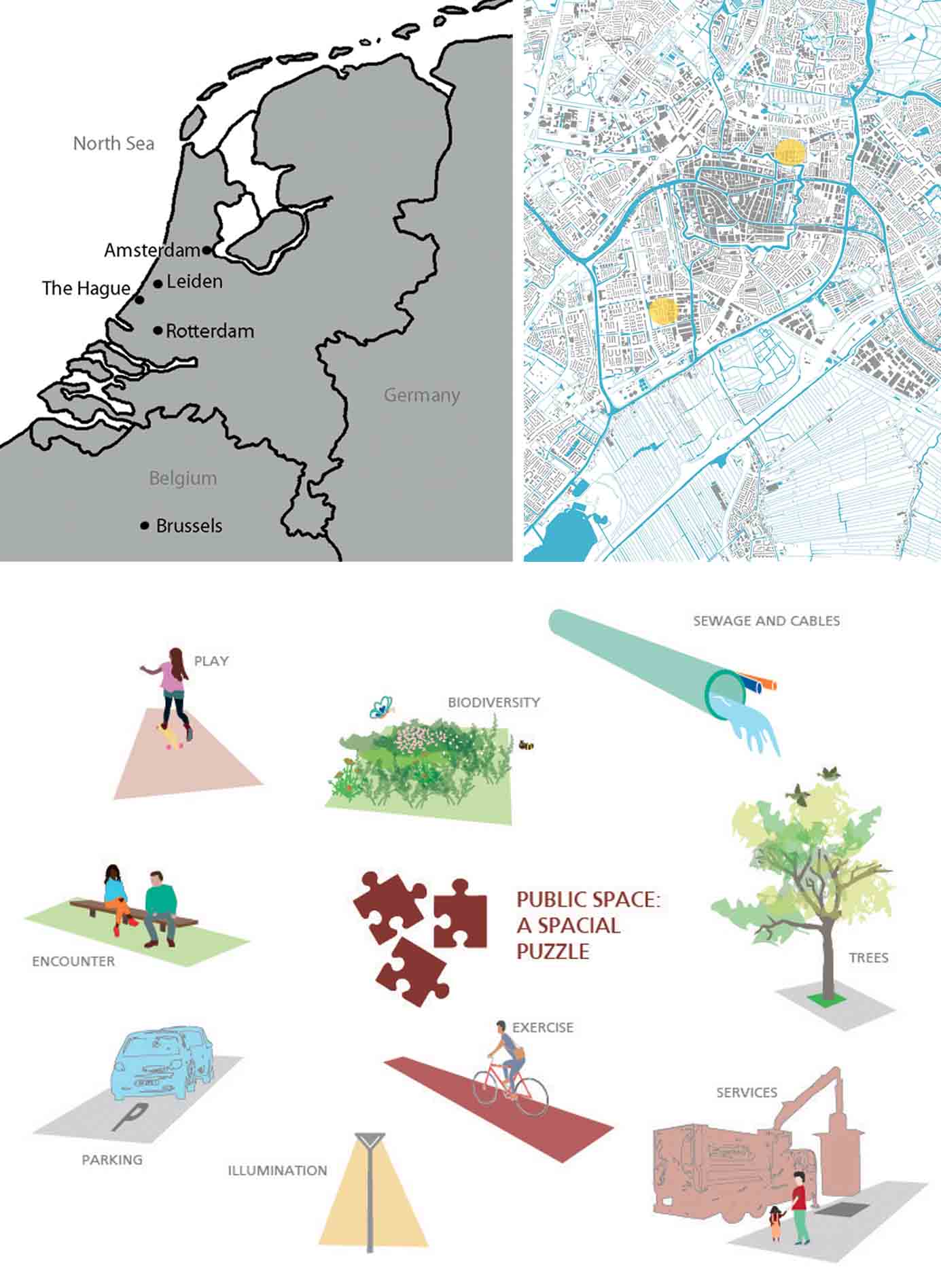

Since over 60% of the country is below sea level, it’s not surprising that Climate Change is a serious issue in the Netherlands. This of course applies to the city of Leiden too, a medium-sized town between Amsterdam and The Hague, with a population of approximately 125,000 citizens. It is characterised by its historic city centre, multiple cultural institutes (e.g., the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre), the oldest university of the Netherlands (Universiteit Leiden) and a densely populated urban area.

Besides Climate Change adaptation, Leiden and a large area of the Holland Rijnland region, are facing major challenges in terms of housing, sustainability, transition towards green mobility and the recovery of biodiversity. Leiden alone has the political goal to build an additional 8,500 houses on an already densely occupied surface, with limited free space and boundaries that are fixed. As a result, pressure increases on the available green space in the city and on its already decreasing biodiversity as it simultaneously tries to establish a liveable city.

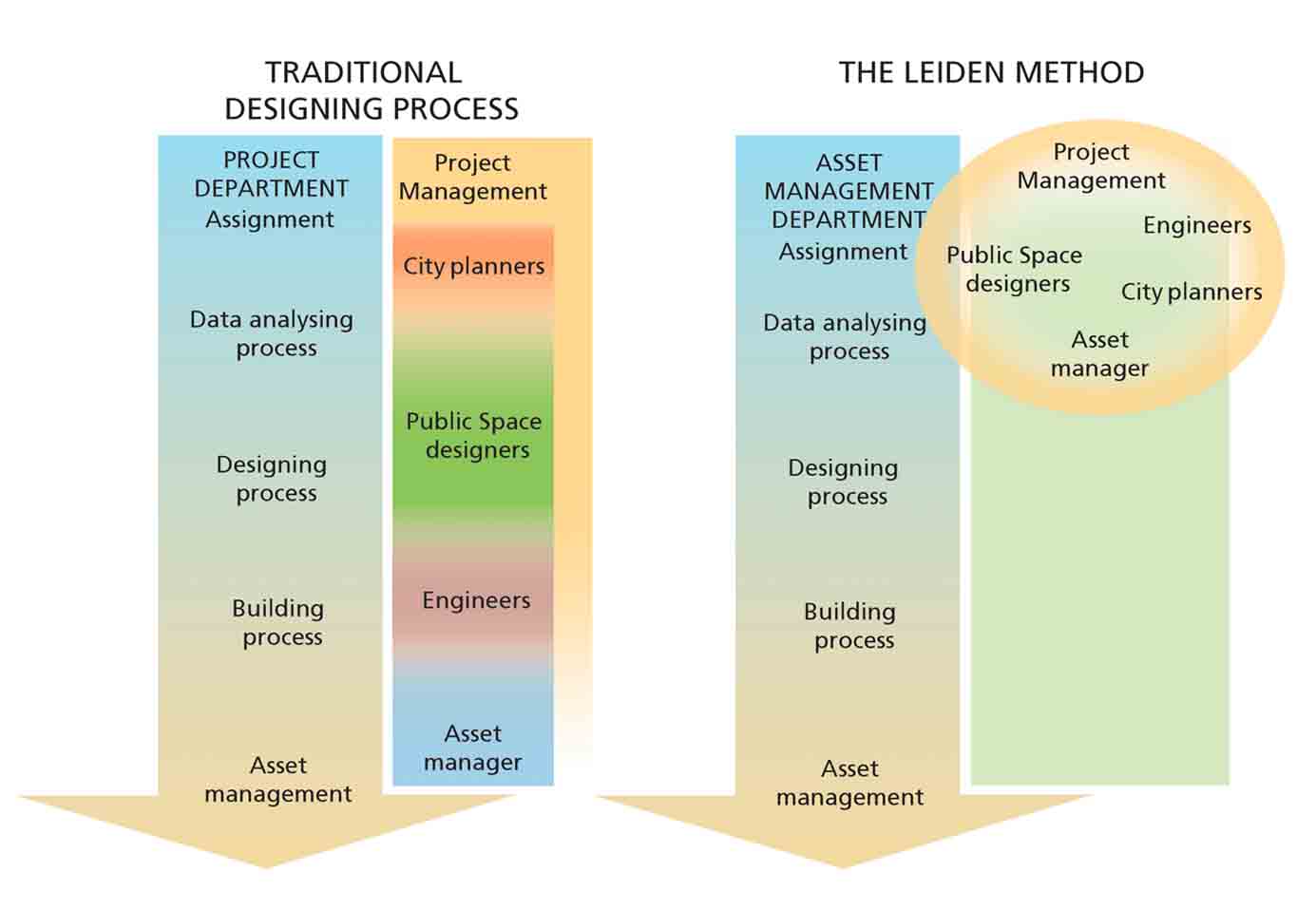

Sewage systems and streets are renewed in Leiden every year in turn in one of the existing neighbourhoods. These renewals are initiated and funded by the local Maintenance Department. The city department for maintenance was in charge of sewage renewal and only the sewage system was renewed, without reconstruction of the entire public space.

The city invested in creating a collaborative design process to tackle issues created by Climate Change. Today, maintenance engineers and designers work together right from the start of the project. We believe this is a necessary condition to transform an existing city into a climate adaptive one.

Since over 60% of the country is below sea level, Climate Change is a serious issue in the Netherlands

Top Right: The two pilot projects in Leiden

Bottom: Climate adaption in a dense city is a complex puzzle

Back to the floods in 2005. The city initially fell back on symptom control and got rid of the water as soon as possible. However, we knew this was not the answer to recurrent floods. The whole organisation of the city was aware of this and several departments started to take action. Plans and initiatives unfolded at the policy-making level and pilot projects were kick-started. All the various ideas and actions contributed to the now common integral (multi-department, multi-disciplinary) approach.

The office of De Urbanisten (Rotterdam) was asked to investigate solutions suitable for Leiden’s new climate adaptive projects. They started with open workshops in which all government departments participated, not only from Leiden but from other local governments too and also included local citizens. All of them shared ideas about methods that could be adapted to overcome their problems. The practicality and manageability of the projects were checked early in the process.

Meanwhile two pilot projects were selected:

1. Noorderkwartier Oost (SPONGE – European project, on stakeholder communication; in 2017 the European initiative of ‘SPONGE2020’ subsidised projects in Leiden to help those areas of the city that were most in need and in danger because of Climate Change).

2. Gasthuiswijk (Project of the department of maintenance – sewage system replacement).

Both projects started in a traditional manner, researching the city planning, the history of the area and traffic structure. But practical research data on Climate Change was mostly missing. The integrated workshops helped to highlight the urgency for a solution. Climate maps were produced by the Province of Zuid-Holland and the waterboard. Meanwhile, the management of the Leiden municipality started to adjust schedules of departments that had so far not worked together. This enabled the city to start projects in which different types of work could be implemented in the public space simultaneously. Also, budgets were critically analysed and put together in an unconventional way. In contrast to budget allotment for roads and sewage systems, the municipality didn’t have a fund for the renewal of green areas every 40-50 years. Today, this is very necessary to implement climate adaptive solutions. Over the years a new working strategy has emerged in Leiden’s departments, which is still being continuously improved upon. This new way of working was supported by the local politicians who understood the need for solutions to Climate Change and realised growing biodiversity and green areas are important. These have now been officially established as city policy.

The Leiden Methodology

In Leiden, plans and projects for the public space by different municipal departments are combined and coordinated in advance. Based on this coordination, a programme has been set up for the coming years for those districts of Leiden that need to be redeveloped with climate adaptive measures. An estimated amount of budget has been reserved for future climate adaption solutions and their maintenance. Traditional research is complemented with additional topics such as heat-stress maps by the province and the waterboard. Specified information is available through the so called ‘climate stress test’ which is updated by civil engineers monitoring the local situation in Leiden. The above-ground situation is completed with the underground situation: pipes, cables and tree roots. Also, a reservation has been made for future transition from fossil to more renewable sources of energy.

Noorderkwartier Oost

The SPONGE2020 subsidies have enabled an intensive process to inform and ensure participation of inhabitants and other important stakeholders. In the evenings, events were organised at the local community centre, which gave people the opportunity to create cardboard models of their own streets. Ideas were given form by using a water table, planting market and an information-cargo-bike.

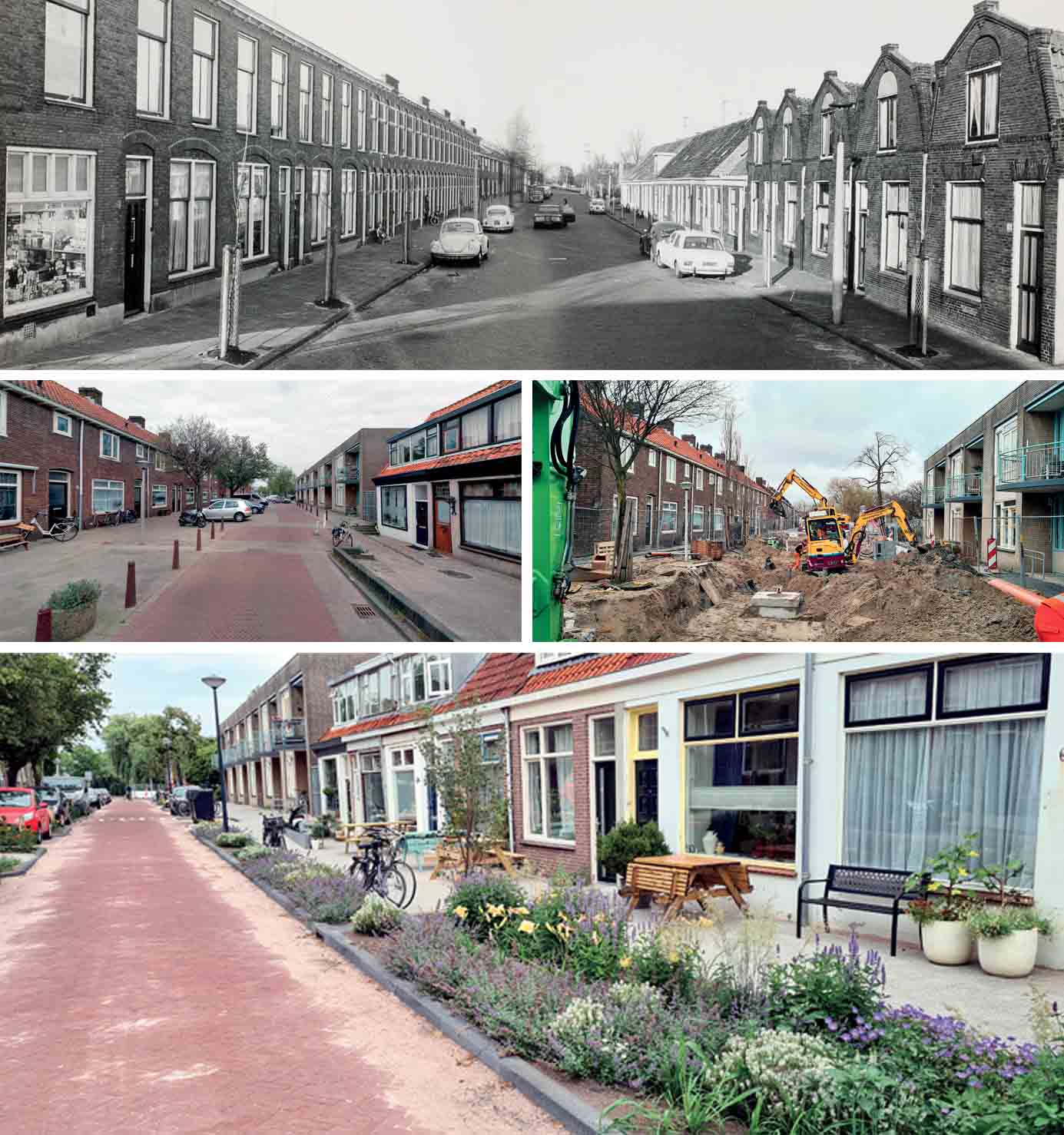

Located at the northern part of Leiden and next to the famous ‘Singel’ (ramparts from the 17th century), the ‘Noorderkwartier Oost’ district is made up of small houses built between 1917-1920. Constructed as a dense housing area, most of the houses have no front yard and stand directly on the narrow streets. Most of these buildings were originally owned by housing associations and were rented out. A growing number, however, are being bought by young people or being split up into smaller units. This makes the community and the appreciation of the public space very diverse. In 1980, parts were replaced by new housing, which are to an extent responsible for today’s problems. With a different ground floor level, the new additions create flooding in the lowest parts. Floods were the most visible issue here but an invisible, more damaging one is drought. The extreme dry summers of 2019 and 2020 caused a significant decline in the groundwater level, increasing the danger of major damage to dwellings mostly built on wooden foundation piles or no piles at all. Additionally, because of layers of peat in the soil, houses continued to sink. Over the last decades some of the older dwellings sank almost two feet below street surface.

Today, maintenance engineers and designers work together right from the start of the project

Next, to control flooding in the future, the sewage system needed to be replaced. The old one was used for wastewater as well as rainwater, causing uncontrollable peak loads and reverse streams of sewage system dirt into the houses. All these issues made the design rather complex and the setting up of an extra and costly pumping system as a ‘mini-polder’ in two streets unavoidable. The project is a pilot for climate adaptation solutions, being a living laboratory to make the soil function as a sponge while having a high groundwater level most of the time. A combination with traditional sewage systems is necessary. The coming years will confirm the theory.

The issue of heat stress in summers and the problem of excessive water run-off due to more frequent torrential rains through the year is being tackled by reducing the number of car-parking areas (and consequently hard landscaping) and substituting these areas with plants. This also creates better growth conditions for trees, increases biodiversity and retains water in the soil, making the city more liveable. Saving most of the existing trees might seem a minor issue compared to all the technical challenges, but it was one of the most important aims. Big trees have a huge influence on the temperature in cities, especially in narrow streets with maximum paved surfaces. New trees need time to grow before they can have the same impact. Although parking space was decreased, the new parking lots were updated to fit modern car sizes and so were the widths of roads to favour accessibility for emergency services. They all fit in like a tight puzzle: planting areas, trees, parked cars, bicycle stands, light poles, places for waste containers, etc.

Middle Left: Previous situation, Noorderkwarter Oost, Julianastraat

Middle Right: Sewage work in progress, Julianastraat

Bottom: New situations, Noorderkwartier Oost, Julianastraat

Gasthuiswijk

The district of ‘Gasthuiswijk’ is located to the west of the city centre. This area was built from 1959, based on the Rotterdam CIAM neighbourhood idea, a popular concept in post-war Netherlands. The rebuilt cities were developed according to the idea of containing socially joined neighbourhoods with their own services. There’s a mixture of housing types, such as family housing and high-rise apartments. A lot of the houses are rented dwellings and owned by housing associations. Only a small number is private property. The district has a spacious layout with a green area in the centre where neighbourhood services such as a church, a football field and a playground association are located.

Reconstruction started because of the urgent replacement of the sewage system. In the past, the standard procedure used to be to lift the pavement, replace the sewage system and close the road again. At the start of this project the added task was to implement climate adaptive solutions, stretched from façade to façade and add more green areas which contribute to the city’s biodiversity. For those additional tasks the municipality provided extra money.

Gasthuiswijk was designated as the first district to be detached from the public gas supply. The plan was to connect to a district heating network, for which space was reserved in the profile. This project has been designed by a team comprising the municipality of Leiden, the contracting company G. van der Ven BV, landscape architects from wUrck, the communication agency of Beaumont and the engineering firm Tauw. To begin with, the intention was to use bioswales, but since the groundwater level was too high, the plans were changed to create an open water system. The result is an enormous transformation of the district: wide lawns and big trees in the centre will be replaced by a varied area with plants, open water and flowering edges. The biodiversity will be increased by choosing gentle slopes and native plants. Over the past decades the area had been confiscated by parking places for cars and pavements; these are now transformed into planting areas. If it is technically possible, most of the rainwater will be transported directly to open water and planting. The climate adaption assignment results are a quality improvement in this district. For instance, the centre services will be relocated to a better spot, the playground will no longer be hidden behind high planting and fences but more in the open next to the new water element.

The water quality was an important issue. The newly built water reservoirs are connected to the existing water outlets in the area. Besides those connections, the new water element is supplemented in dry periods by pumping up rainwater from a new drainage system to ensure enough water circulation in all circumstances.

Floods were the most visible issue here but an invisible, more damaging one is drought

Right: Future situation, Gasthuiswijk

Conclusion

As mentioned earlier, the method of Leiden’s approach is a work in progress. The municipality likes to invite external participants to collaborate. Housing associations weren’t willing in the past to disclose their future schedules but now they recognise the benefits and are more than willing to contribute to a new project in the Meerburg neighbourhood. Recently, the cable and piping companies were convinced and have signed a collaboration contract with the city of Leiden. They have separate schedules and agendas but are essential partners for the success of these projects. The municipality wants to avoid new road work in streets for the replacement of cables and pipes, just after reconstruction has taken place. The city expects to benefit from a more integral approach by also managing the extreme filled ground below the street surface. Although it would be best to remove the rainwater drains and lead the rain directly to open water, not everyone is convinced this will technically suffice. But it could save money and space.

At this moment parts of Noorderkwartier Oost and Gasthuiswijk are under construction. New projects are already under preparation and will start in the coming years, like Professorenwijk, Vogelwijk and Meerburg. These projects will be based on the lessons of the last six years and will definitely benefit from the collaboration of the different departments, operating ‘on the same page’.

All photos: Author

Comments (0)