The government is all set to develop 100 new smart cities that will become prime centres of employment along major transportation corridors across the country. These are expected to be modern townships with highrise towers, an up-to-date services network, an efficient transportation system and lush landscape. A prototype framework of this futuristic concept may perhaps help define a clear direction. To begin with, some smart cities could very well be built close to growing urban complexes or even within established townships. Such development would help to improve and consolidate existing urban areas.

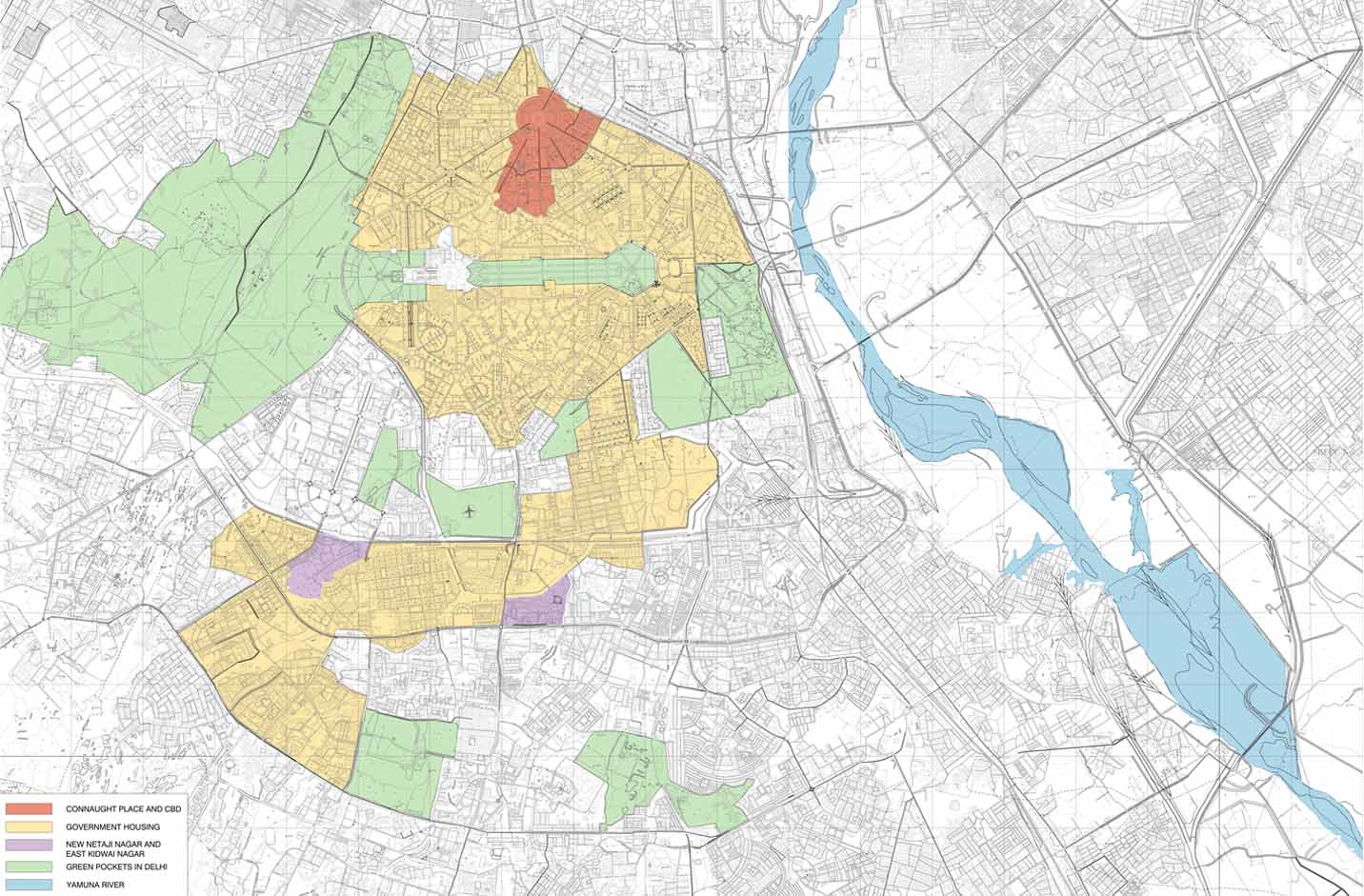

Looking at the plan of the capital city of Delhi, one realises that a substantial part of what is now the central area consists of housing for government officials which is run down and ready for renewal. The area of this land is more than 3000 acres. So why not consider building a high-tech smart city centre in the heart of the capital itself? Considering the availability of sizeable parcels of government land and the new regulations permitting intensive high rise development, this would be a very realistic proposition. A sensitively worked out and detailed urban design proposal would help create a major new focus of activity for the rapidly growing population of the city.

Concentrated high density development in this prime location would be much more attractive than a series of high intensity zones strung along the metro corridors. Apart from generating substantial profit for the government, such a project would act as a trigger for comprehensive urban renewal in other areas. For effective implementation however, the Ministry of Urban Development will have to put a stop to the current practise of piecemeal development of government land.

The areas of government housing in the centre of the city consist of two large parcels. The area of Sarojini Nagar, Lakshmibai Nagar, Moti Bagh, Netaji Nagar and Ramakrishnapuram, which are all contiguous, is over 2350 acres and the triangular area west of Connaught Place bound by Baba Kharak Singh Marg, Mandir Marg and Panchkuin Road is more than 550 acres. Both these pockets of land are eminently suitable for comprehensive redevelopment.

A prototype framework of this futuristic concept would perhaps help define a clear direction

Leaving in place the major roads that serve this area, along with existing parks and selected major buildings, it is possible to develop a totally new and independent traffic network with all the latest high-tech systems to enable handling of the increased volume of traffic. This can be effectively integrated into the metro rail system and the proposed future rapid bus transport system for the area.

An updated high-tech underground infrastructure network can be simultaneously laid out to provide efficient distribution of IT services, electricity, water, drainage and sewage treatment. A system of service tunnels or even a completely separate level catering to unimpeded car movement, along with a sizeable services network effectively taking care of the complete future services needs of the skyscrapers above, would help bring about a new approach to the development of this high value land. Coupled with multi-level parking above grade, landscaped decks, a linked system of bicycle tracks and a continuous pedestrian network, this would completely transform the area. Such a development would be much more cost effective and easier to implement than providing several levels of below ground basements for parking and services.

Multi-storey structures above can be planned to provide up-to-date new government housing, replacing all the existing dilapidated units, along with substantial public housing serving different sections of society. Together with the necessary support facilities, like community centres, hospitals, schools, fire stations and electric sub-stations, this would help meet the needs of all residents.

Within the proposed urban complex there would be enough space for a new civic centre, as well as a commercial complex, highrise office towers, shopping malls, cinemas and meeting halls. These could be linked to a system of parks and recreation areas with substantial open spaces to cater to a wide range of community activities like weekly bazaars, haats, Rahgiri type get-togethers, music sessions and open air theatres. Implementation of the total development can be done on a process of cross subsidisation to cater to all sections of society, instead of developing this area only for the use of middle and upper income groups. A detailed plan properly worked out could be constructed section by section in stages, over a period of time.

Concentrated high density development in this prime location would be much more attractive than a series of high intensity zones strung along the metro corridors

Recent development of New Netaji Nagar near Moti Bagh and the proposed rebuilding of East Kidwai Nagar reflect a shortsighted approach. In New Netaji Nagar, on a site of 110 acres, only 492 residences for government officials have been built where, as per current building regulations, 7500 dwelling units could have been built to accommodate 37,500 residents. In East Kidwai Nagar on a site of 86 acres, 4747 apartments for government bureaucrats are currently being built. In accordance with prescribed government housing norms, a series of similar multi-storey blocks has been unimaginatively laid out in a prominent location with limited communal facilities pushed to one corner. A site of approximately eight acres facing the Ring Road has been earmarked for commercial development to be leased to developers. In order to meet parking requirements, three levels of basement are being built. Despite this being labeled as a high density development, the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) of 203 is way below the prescribed norm of FAR 300 for this area. It is unfortunate that, at a time when there is increasing pressure on the need for maximum development on land in urban areas, government land is being grossly underutilised

Government land is public land, which needs to be developed with the larger interests of the city population in mind. In this day and age, it makes more sense to build large scale integrated development, instead of separate gated enclaves for civil servants. In the context of the city’s future the current insular attitude needs to change.

Ranjit Sabikhi is an award-winning architect, with wide experience in architectural education, architectural practice and urban design.

Comments (0)