There’s certain innocence in people who don’t believe human mistakes have led to climate change. Our successes during the industrial revolution gave us practical magic; the benefits have grown mundane, yet remain recognisable and transformative. Over controlled flame, we sanitise dinner. Under electric light, we accomplish more goals before bedtime. Behind the wheel of a car, we have more good jobs within reach.

The production and consumption of food and energy, however, create greenhouse gases and feed the catastrophe of global warming. Denialists take this reality as a personal insult; born into our societal habits, it is natural to perceive them as good. This perception is an incredible obstacle to living differently. One unusual method is to reduce participation in adverse practices. How might we highlight invisible links between the environment and ourselves as well as impart a sense of stewardship? Can we construct helpful simulations?

The Water Garden 2.0 features aquaponics farming, which links fish and plant life. The waste from fish provides nutrients for edible herbs and vegetables. This system draws into sharp relief the interdependence between life and natural resources. Human intervention is key, since maintenance ensures survival of bacteria and smooth operation of the water pump. A balance must be conscientiously monitored; evidence that the equilibrium of the real-world environment is similarly delicate.

As such, our daily routines do rely on cause and effect. If we eat healthy, we grow strong. If we study hard, we earn opportunity. If we hold a good job, we nurture our families. These are lazy oversimplifications, but they signal that we each have a recognisable sphere of influence. It is easier to notice when our actions show effects right under our own noses. Perhaps this may be a reason some people just don’t trust recycling. There isn’t a simple way to verify if our old aluminum can or cardboard box is now something new in its second life.

Environmental patterns follow inconceivable timescales that are hopelessly out of step with our natural senses and lifespans

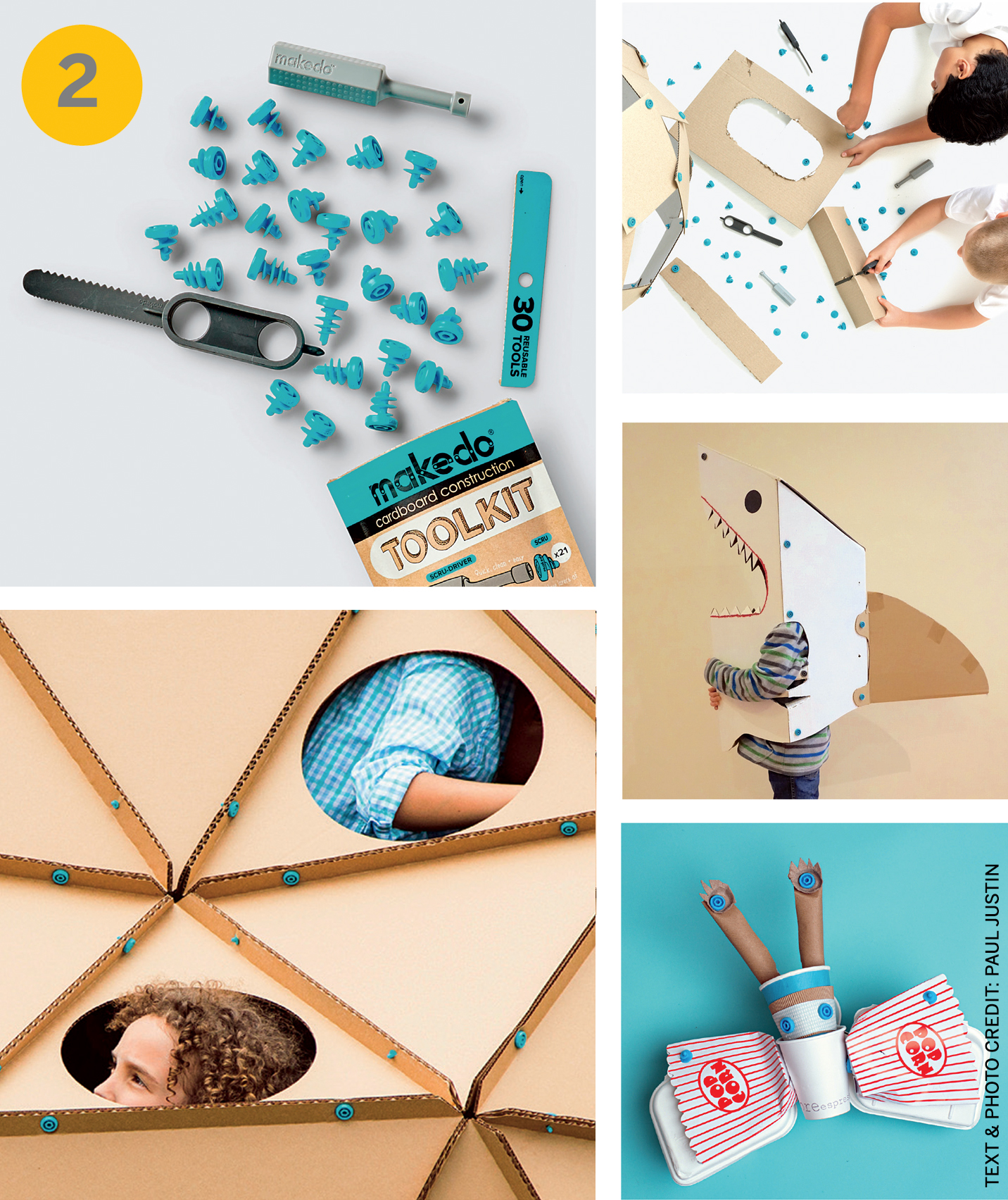

Makedo is a system of re-useable screws, fasteners, hinges and other tools used to join cardboard scraps into structures, costumes, creatures and more. It has an incidental function of helping kids and adults quantify their ‘paper footprint.’ While industrial recycling processes are hidden, Makedo gives immediate feedback. It allows us to be thoughtful in our consumption of plant-based resources.

Similarly, the effects of climate change can be seen and felt; it is the mechanisms causing it that are easier to overlook. Environmental patterns follow inconceivable timescales that are hopelessly out of step with our natural senses and lifespans. How does anyone develop care for the earth? Can we manufacture altruism?

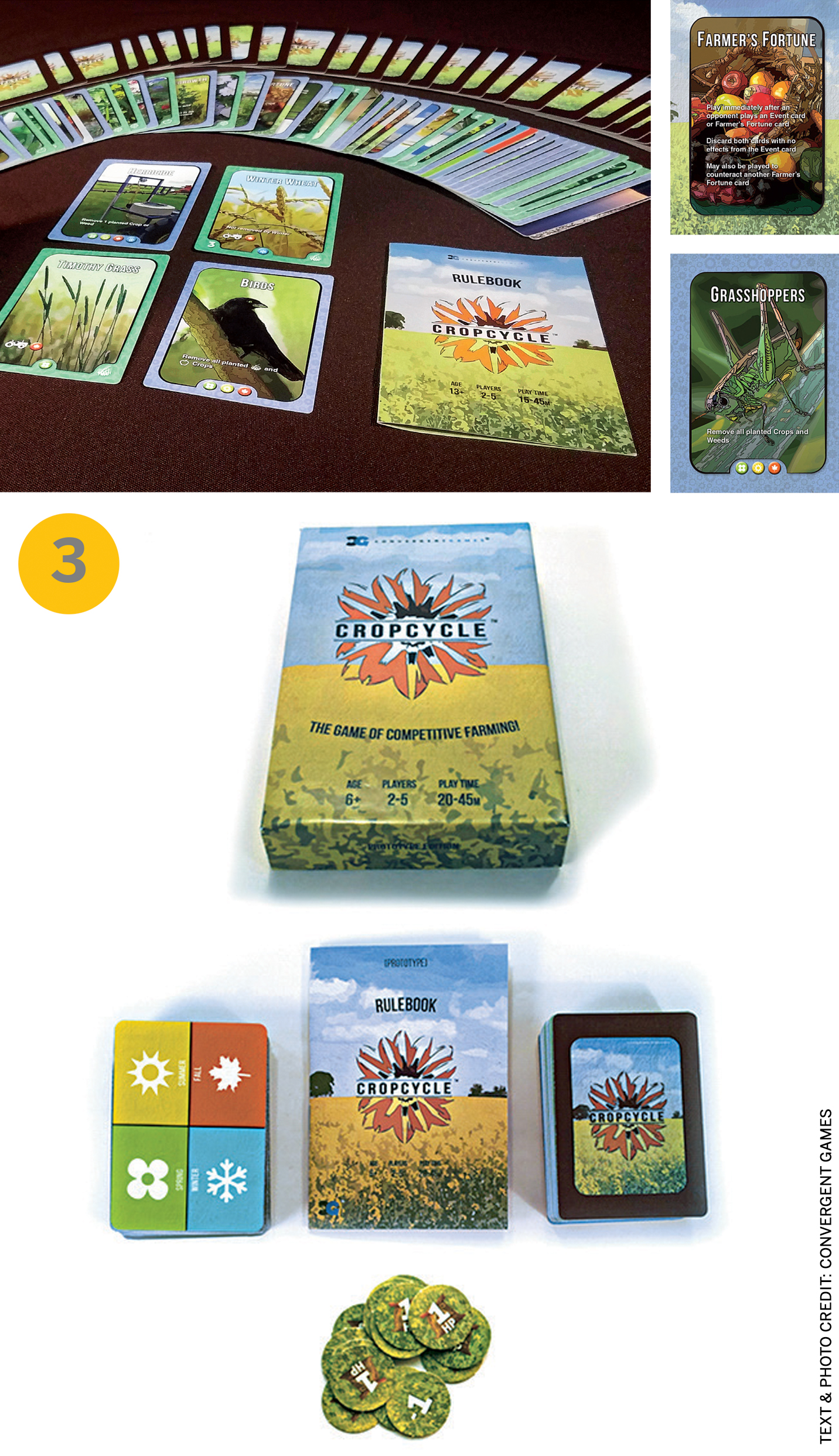

Crop Cycle is a competitive card game where players raise crops that are best suited to each season in the year. They must adapt to changes in resource availability and to obstacles such as proliferation of weeds and chance weather events. It might seem to pit humans against nature. But multiple play sessions reveal the volatility in agriculture and how cooperation with the environment drives success. Crop Cycle prompts us to analyse our food purchases.

We can’t expect everyone to become an expert farmer or environmental scientist. So how do we move forward? There’s a saying, “Society progresses when old men plant shade trees under which they know they will never sit.” It is difficult to prove who said this first, or the original nuance. But if our crisis response hinges on altruists, we have to distill meaning, make it provocative and translate it into everyday products to gain attention.

The Water Garden includes easy-togrow wheatgrass and sprouts because they grow quickly and require minimal light, making them ideal for kick-starting the natural cycling of your tank.

The Water Garden condenses all the amazing features of large-scale aquaponics into a 3-gallon tank for your kitchen or classroom! You can grow organic herbs and microgreens with this closed-loop ecosystem.

The water from the fish tank is pumped to the plant grow bed, where beneficial nitrifying bacteria growing on and around the plant roots convert the ammonia-rich waste from your fish into nitrites and then nitrates. The plants then take up the nitrates as the nutrients they need to grow.

Additional info: www.backtotheroots.com

Makedo is a catalyst for critical thinking because it fosters the natural inclination of the child to learn by doing.

Makedo is a simple to use, open-ended system of tools for creative cardboard construction. Build imaginative and useful creations from upcycled (repurposed) everyday cardboard. Makedo comes to life in collaborative, creative environments such as classrooms, maker spaces, museums and of course homes.

The Safe-saw™ allows kids to saw and punch cardboard without the need for sharp or pointy tools and the specially designed Scru and Scrudriver make connecting layers of cardboard far more intuitive and effective than other alternatives. Makedo can be reused over and over again to build anything the maker can imagine.

Additional info: www.make.do

Crop Cycle has a farming theme and draws on agricultural concepts, but is designed to be accessible to players of all backgrounds.

Farm to win! You are a farmer navigating the four seasons and the challenges of nature. A seasons mechanic limits when cards are played, creating challenging choices for players at every turn.

Hold onto cards to ensure you can protect your crops and avoid catastrophes, or push your luck and hope for a safe harvest! Strategy, luck and perseverance will determine the victor!

Additional info: www.convergentgames.com

Comments (0)