As many a New Yorker will tell you, autumn in the city brings magical moments. The air is crisp yet comfortable. Wearing a light jacket, you can walk all day, zigzag across avenues, stop by a café, perhaps step into a museum, experiencing the city as a shared landscape. Sultry summer streets have been rubbed clean by rainwater. Fall winds swirl through the rivers, estuaries and freshwaters, giving the city a shoreside scent, reminding us that we’re on an island, just a stone’s throw from the Atlantic Ocean. Sunlight plays on the city’s red bricks, the whites of its marble, the silvers of its steel, casting the skyscraper-flanked streets in haloes rarely witnessed in other seasons. Days like this, just being outside makes you feel lucky and lifts your spirit.

Though it has been a while since I called myself a New Yorker, I spent some time in the city recently, and mostly what I wanted to do there was walk. Walking, an activity capable of enhancing one’s environmental perception, is at the heart of the science of strollology as coined by Swiss sociologist Lucius Burckhardt. Walking is also a way of letting go of thought, merging with the wider flow, feeling one’s place in a communal ballet of which human activity is only a part.

Making my way across West 87th street towards Central Park on a sunny October day, all around me, the light and leaves were dancing. I walked beneath a canopy of street trees and past a community park — a quiet pocket of green where three people sat reading, two with steaming cups in their hands. As I reached Central Park, its green carpets rolled out before me, clearing my head of yesterday’s stress. I made my way around the Reservoir in a kaleidoscope of colour as the leaves of London Planes, American Elms and Black Tupelos exploded in the crimsons and golds of rebirth, their vivid bundles falling like silent fireworks.

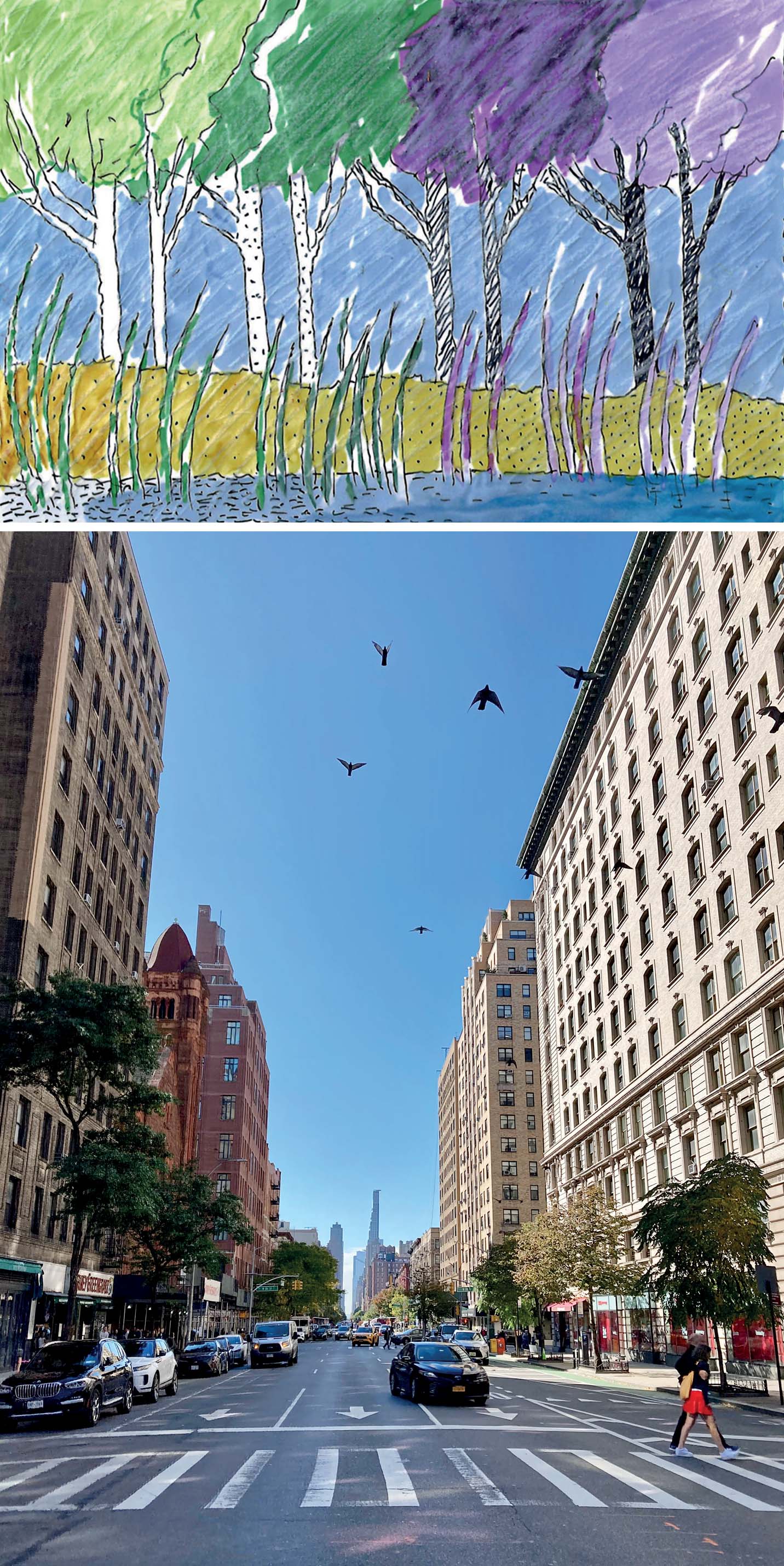

Bottom: Crossing Columbus Avenue on an autumn day in October

After the loop, making my way back towards the street west of the Reservoir, my eyes fell upon something else, something new, a string of signs I’d never seen, offering information about a settlement known as Seneca Village, which was a thriving black community that existed on these same grounds in the 1800s. Seeing these signs for the first time, my body flooded with recognition. They were new to me — I’d not been in this part of the park since 2019, the year they were installed — but the story of Seneca Village was familiar. I’d heard about it well over a decade ago, from a friend I often walked weekends with here. I remember him well because he was one of the first to show me how a shared space could be sensed so differently. He saw this park in a way I did not, though we both loved it, because his father once told him stories of the free men and women, his ancestors, who’d established their successful, historic community here. “Where are the traces of them now?” he asked. They were nowhere to be seen back then, but today, perhaps even thanks to him, the history has become more visible, better acknowledged by this landscape, reflecting a wider change of thought.

As the day passed and I rambled through more of the city, I noticed other physical changes that were evidence of a change in our mental landscape — sidewalks that had been closed to cars and opened to pedestrians during the pandemic, restaurants turned inside out, overflowing with plants, partly overtaking the streets. All this had been instigated by the needs and desires of people living through a pandemic, a change in our mental state that reflected a change in our physical use of public spaces.

Though many of a landscape’s affordances are shared, each person has affordances unique to them

Burckhardt would have likely championed these urban changes prompted so immediately by citizens in need. After all, his notion of the science of strollology was partly meant as a critical reflection on urban development. He believed the planning and politics that go into the creation of cityscapes is often too removed from the people living in them. He was stringent in his call for participatory urban planning. He saw the citizens of a space as its experts and understood that an experience of place was also an experience of personal and communal history and development. It was, to use a term from psychologist J.J. Gibson, always an experience that depended upon ‘affordances’ — on a cumulative sense of the world, and on what that world allowed or afforded them. Though many of a landscape’s affordances are shared, each person has affordances unique to them and their experience, because each person has trodden a unique path.

Affordances are opportunities for behaviour. They are the actions and potentials inherent in our environment, and though the environment is shared, what it affords a person depends on their history and development. The same space or object can afford very different actions. A baby will use a set of keys differently than an adult. An insect may see a log in the forest as lunch, while a human may approach it as a place to rest. I had one story of Central Park, while my friend had another.

We each experience the same city differently according to all we have experienced before, and the city does well to acknowledge this. A market square is experienced one way by the vendor working long days there, and another by a shopper briefly stopping by, but each is important to the other’s lifeworld. As we move through our cities, we have unique affordances, unique readings, and not all spaces afford us equally. Urban design at its best — or so Burckhardt, Gibson and others have suggested — supports each unique stance while also prompting and instigating communal creation and discovery. It sets a rhythm to which all instruments can harmonise and improvise.

A city is an ongoing encounter of sensory regularities — shapes, sounds, colours, smells, sensations — sensory regularities that shift in and out of one another, overlap and cohere into what Burkhardt (in Why is landscape beautiful?) calls a string of pearls: Each pearl is a cluster of sensory impressions, sensory regularities grouped into collections, be those restaurants, forests, churches, homes or the string of pearls we call Central Park. All these pearls are physical, but they are also social and mental. The pearl we call home is a physical place, but it is also an idea and a feeling. There is always something material and something imaginary to any place that has become meaningful, and though most sensory regularities are mostly shared, they are always framed according to our histories and affordances.

There is always something material and something imaginary to any place that has become meaningful

In other words, mental, social and physical landscapes are always co-creations and never neutral. The ways we design and access our cities and communities are also the ways we set the parameters of our potential mental and social affordances. The way we move through public spaces — how we find our way through a park, through our thoughts, or through a book — is a shared stroll on some level, a trajectory of the affordances we notice and champion, and of how we learn and share those affordances with others as we navigate. Working in urban ecology and landscape can also mean working in the fields of physical and mental health: Designing streets and urban forests, buildings and gardens, sidewalks and signage, also means designing potentials for memory, feeling, and thought, and for how we might connect minds and share paths in ways that stimulate and benefit the citizens living in them.

Part of good design, as Burckhardt saw it, is understanding this mental side of landscape and including spatial interventions, stimulating sensory elements to awaken and enhance our mental lives and knowledge. Signs such as those of Seneca Village are there to do just that, to alert one to another reading of a familiar landscape, but they can also be placed in such a way that even those who walk by them every day never see them. Every choice matters.

This brings up another of Burckhardt’s notions: a city’s invisible design, the idea that all landscapes are internal, that what gets built begins with mental parameters and confirms social ones. Just as the timetable of a bus stop or subway may dictate the hours of its nearby kiosk, or the size of a kitchen may determine who and how we gather, the design of a park may prompt us to wonder.

Cities awaken and stimulate our senses with their activity, their height and light and extremity, but they can also become sanctuaries of intimacy, health and connection, places with paths grounded and shaped around authentic connections that are consistent and dynamic. The physical bodies, objects and organics around us are raw material for the eventual scripts and patterns of our thoughts, feelings and memories; mental life is always nested within spatial experience, patterned by its affordances.

What materials we use and how we arrange them matters for mind and body

As Burckhardt and others like Henri Lefebvre — with his corresponding notions of l’espace conçu, l’espace perçu and l’espace vécu — have shown, landscapes are always physical, social and mental. They offer affordances for both minds and bodies. How those affordances affect our health depends on the trajectory of each person over time and those trajectories form the city’s communal ballet. Taking this seriously means remembering three touchstones for how we design, plan and access shared space:

1. History matters. It must be acknowledged. To understand what affordances are being given, accentuated, erased or saved, we must know one another’s stories and trajectories. That is true of all the forms of life that make up a city (plants, animals, insects, etc.), not only the human ones.

2. Sensory arrangement is never neutral. It always contributes (for good or ill) to both mental and physical health. What materials we use and how we arrange them matters for mind and body. Cities must take their sensory affordances into account, not only as means of navigating physical spaces but also as means of navigating and exploring mental ones.

3. Movement is the ultimate affordance.

A primary concern of all urban design is how it allows us to move and what sort of movements it affords all its citizens. Can we walk with the autumn leaves and light without worrying about noise and traffic? Can we meet strangers in the streets? Are community stories scaffolded and given space to stretch?

Just as the memory of a song shares the patterns of its original music, other thoughts, feelings and memories share the patterns and resonances of the sensory landscapes in which they develop. How we shape the parameters of our cities is how we shape our senses, and how we evolve and extend those senses individually and communally depends on what affordances we highlight or notice. Trees, homes, buildings, streets — these are landmarks of memory, knowledge, feeling and trust. They cue, trigger and set inner boundaries.

Every aspect of the city is mental as much as physical. Nothing is neutral to our health. We cannot separate thoughts, feelings and memories from plants, bodies and bricks. When we design public spaces — be those physical, mental or social — we design inner affordances. We are always creating inner landscapes alongside outer ones.

All photos: Andrea Hiott

Comments (0)