Design is continuously in motion. The evolution of everyday products is directly or indirectly correlated to the constant transformation of our society, culture, lifestyle and technology. While many products are timeless in use, function and form, a large category of consumer goods is subject to different market dynamics and change throughout their life cycle.

New products and styles are introduced in the market periodically, gain popularity through acceptance by more and more consumers, reach the stage of maturity and then go out of acceptance. New market introductions follow a five-stage process that involves specific consumer groups at each stage: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and late adopters.

At what point do unexpected, cutting-edge, isolated trends and products become mainstream?

From its humble beginnings as an alternative to surfing, skateboarding has grown from a grass roots movement to having international participation and worldwide recognition; it has changed the way we look at the urban environment. The appropriation of the informal skateboard culture into mainstream has been a clear and growing trend and many companies have made it hugely profitable.

As an example, Airwalk, an athletic shoe company, wanted to expand its reach from a niche to the mainstream market. During the brand transformation process, marketing experts translated the trends gained during the research, into a series of ad concepts, which helped to increase the sale of Airwalk products to the mainstream market.

Although the company had initial success among innovators and early adopters, interest soon waned. Within a few years, the brand began to lose its cutting-edge reputation. Then it reached another market segmentation by offering exclusive products that appealed to a larger consumer group. This demonstrates how a niche category can become mainstream through targeted marketing interventions clarifying some brand values while losing some consumer groups.

OneWheel+XR is another example of how a new product category can blend into a mainstream market. Initially perceived as a cutting-edge product, the company is reshaping the way we look at urban mobility, becoming the intersection and crossover among sport, lifestyle and informal mobility.

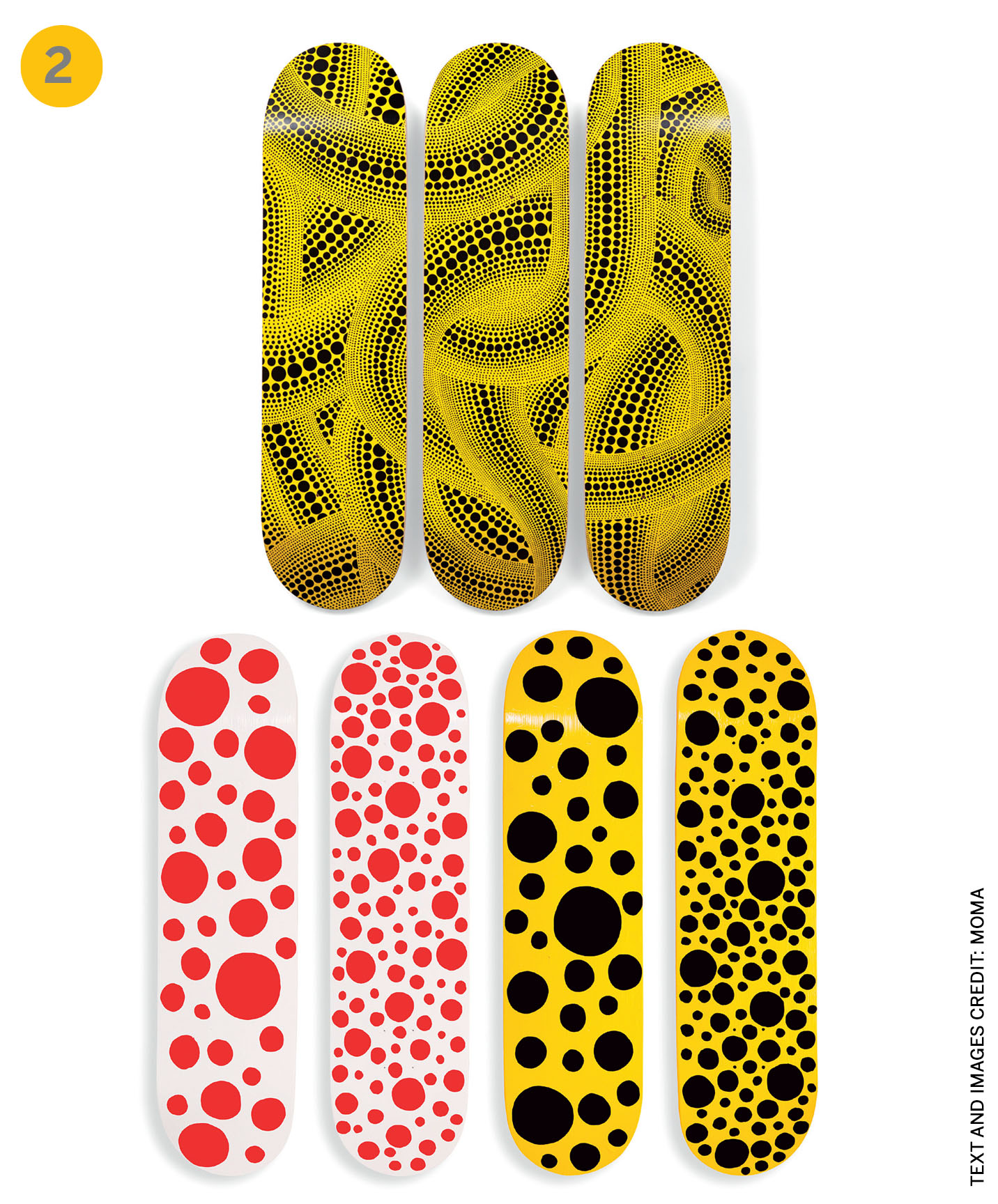

What if a product trend was elevated from mainstream consumption into statement art?

What if a product trend was elevated from mainstream consumption into statement art?

In October 2018, MoMA released a limited edition line of skateboards designed by Yayoi Kusama. The Yellow Trees collection designed in 1994 and the Dots Obsession collection designed in 2018 are classic Kusama. Skateboard painting is not an isolated event, but it is now contributing and elevating the perception of this culture through art.

What happens when cutting-edge technology becomes mainstream?

The adoption framework is especially relevant regarding technology. Near-future and emerging technologies are making their way to mainstream as well and will change what we do, how we do it and how we interact with one another.

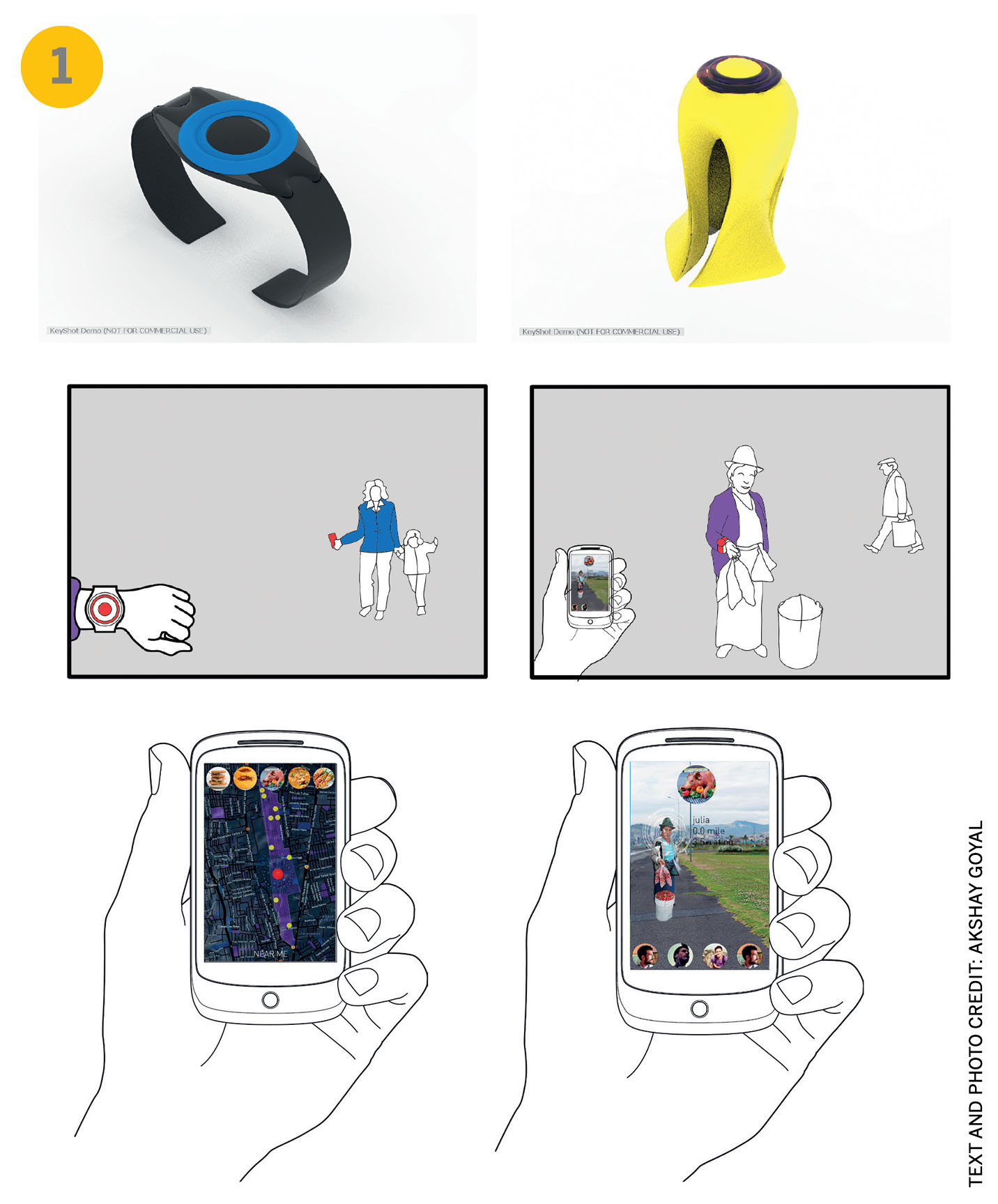

FoodEQ is an augmented landscape Arduino-based project that investigates embedded technology appropriating informal food networks in an effort to link people and places.

While these products may be different in scope and nature, they all show a shift: from elitist to mainstream, contributing, with varying degrees, to the evolution of the urban informality. What about products that are yet to cross over into the mainstream but show potential in influencing behaviours on a global scale? Such products can become important tools in the evolution of sustainable lifestyles, a major area of focus currently. Sprout Pencil, an everyday tool that can be planted after use, is an excellent example.

How might we encourage wide adoption of such products? How might we be good observes and listeners to capture these emerging trends to design a better and more informal urban society? The future is hard to predict unless we design it.

1. FoodEQ>Cambridge, USA>2016

Akshay Goyal

The system is intended to have a three-fold use: leveraging food cultures to connect people, generating interest and activity in the urban precinct of Parque Bicentenario and making the opaque informal sector more comprehensible by mapping information related to it.

The platform is designed around two key user groups: the informal food sellers and the consumers. It consists of a physical beacon for the food sellers, which is coupled with a phone application at the consumer end.

Additional info: http://senseable.mit.edu/papers/pdf/20170525_SCL_Guide_Quito.pdf

FoodEQ is an augmented landscape project that investigates embedded technology appropriating informal food networks in an effort to link people and places.

|

2. Yellow Trees Skateboard Triptych> Canada>2018

Yayoi Kusama

This set of three Canadian maple wood skateboards features details from Yayoi Kusama’s Yellow Trees (1994). Add your own wheels for cool, functional skateboards or hang on your wall as art, with included wall mount.

During the 1950s and ’60s Kusama played a major role in New York’s avant-garde art scene, participating in many events, including a performance at MoMA’s Sculpture Garden in 1969. Kusama returned to Japan where she lives and works today. Her work is represented in MoMA’s collection.

Additional info: https://store.moma.org/prints-artists/artist-products/yayoi-kusama-yellow-trees-skateboard-triptych/139507-139507.html

New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama have teamed up for a collection of skateboard decks.

|

3. Sprout Pencil>Cambridge, USA/Taastrup, Denmark>2013-present

Michael Stausholm

The idea with the Sprout Pencil is that you plant it when it becomes too short to write or colour with. This way you give it a new life by turning the stub into herbs, vegetables or flowers. The Sprout Pencil is 100% natural and biodegradable and is a popular green alternative to company plastic ball pens with a logo.

“We don’t just sell pencils. We are on a mission to be the preferred alternative when it comes to showing that small steps matter when it comes to sustainability. If you can plant a pencil stub, what else can you do to recycle more? This is the spirit that lies in our pencils and in the mentality of the Sprout team.”

Additional info: https://sproutworld.com

Sprout World is also developing the world´s first plantable make-up pencil that they expect to launch at the beginning of 2019.

|

Comments (0)