Bogotá, the city I grew up in, had virtually no provision for public leisure in the early 1990s. By 2007, the city considered leisure as a vital metric for urban equity. Enrique Peñalosa first came to office in 2008 with the belief that quality of life distribution should take priority over income distribution. Now, on his return to office, Mr. Peñalosa argues that urban inequality is more harshly felt during leisure time. High-earning executives spend their time outside of work in sports clubs, expensive bars and restaurants or second homes in the countryside. The poor, however, have few options other than watching television in crowded homes.

Investments in urban leisure can level the playing field for a city’s residents. An interesting perspective on this phenomenon emerges by comparing three cities: Mumbai, London and Bogotá. Urban leisure is not only recreation. Leisure entails three key elements of city living: time, space and place. The availability of time is perhaps the first barrier to equity, with lower-income groups working longer hours and commuting over greater distances. The second barrier is the space available for leisure; for example, parks and open spaces. A final barrier lies in the places that provide options for leisure, from sporting events to arts and culture.

Making time for leisure

The most important and often overlooked enablers of urban leisure are the legal frameworks and the prevailing expectations that affect the time urban dwellers have for recreation. Long work days and lengthy commutes limit free time. Leisure thus increasingly becomes a privilege for those with shorter commutes and manageable work expectations.

The standard workweek in London, Bogotá and Mumbai differs greatly. The average Londoner works around 33 hours, from Monday to Friday. However, those in high-pressure service jobs often work 70- to 80-hour weeks. By contrast, Bogotanos work up to 48 hours per week, as capped by law, most working Monday through Saturday. The workweek of Mumbaikars varies widely, the average hovering around 44 hours. Employment terms are highly unregulated and some people work 12-hour shifts daily with no weekly break.

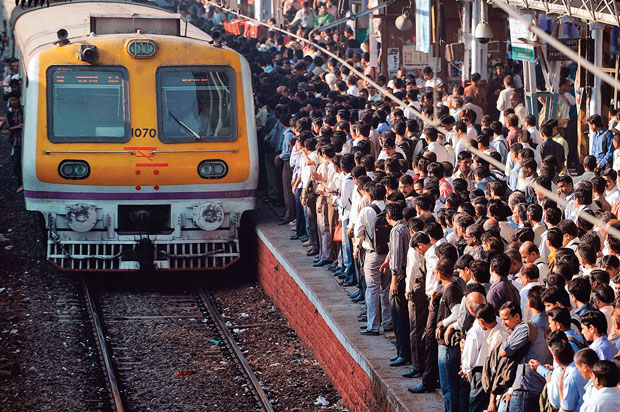

Commuting also limits the availability of leisure time. Megacity Mumbai spans over 60 kilometres from end to end and is arguably the most congested of the three cities due to its extraordinarily high density. An average commuter takes around 50 minutes to reach work and another 50 to get back home. A train ride from the Churchgate business district to residential areas north of Mira Road can take up to two hours, not including last mile commutes.

Investments in urban leisure can level the playing field for a city’s residents

Mumbai has gradually modernised its dated public transport infrastructure with investments like the metro and the monorail. However, these efforts have had nowhere near as much of an impact on commuters as Bogotá’s bus-rapid transit system, TransMilenio, which cut commuting time by 32%. Though initially successful, a series of poor management decisions have decreased the effectiveness of TransMilenio. As a result of congested buses and inefficient routes, the number of private cars on the road has increased in recent years.

London is perhaps the best city for commuters, with people traveling an average of 75 minutes per day; fewer than 40 minutes either way. The London Underground transports 4.8 million passengers daily. On top of that, the bus system guarantees that over 90% of Londoners have stops within 400 metres of their homes. What is more, commuting in London does not only involve mass transit. Last mile journeys along paved, tree-lined sidewalks bring leisure into the daily routine of city dwellers, regardless of their income level.

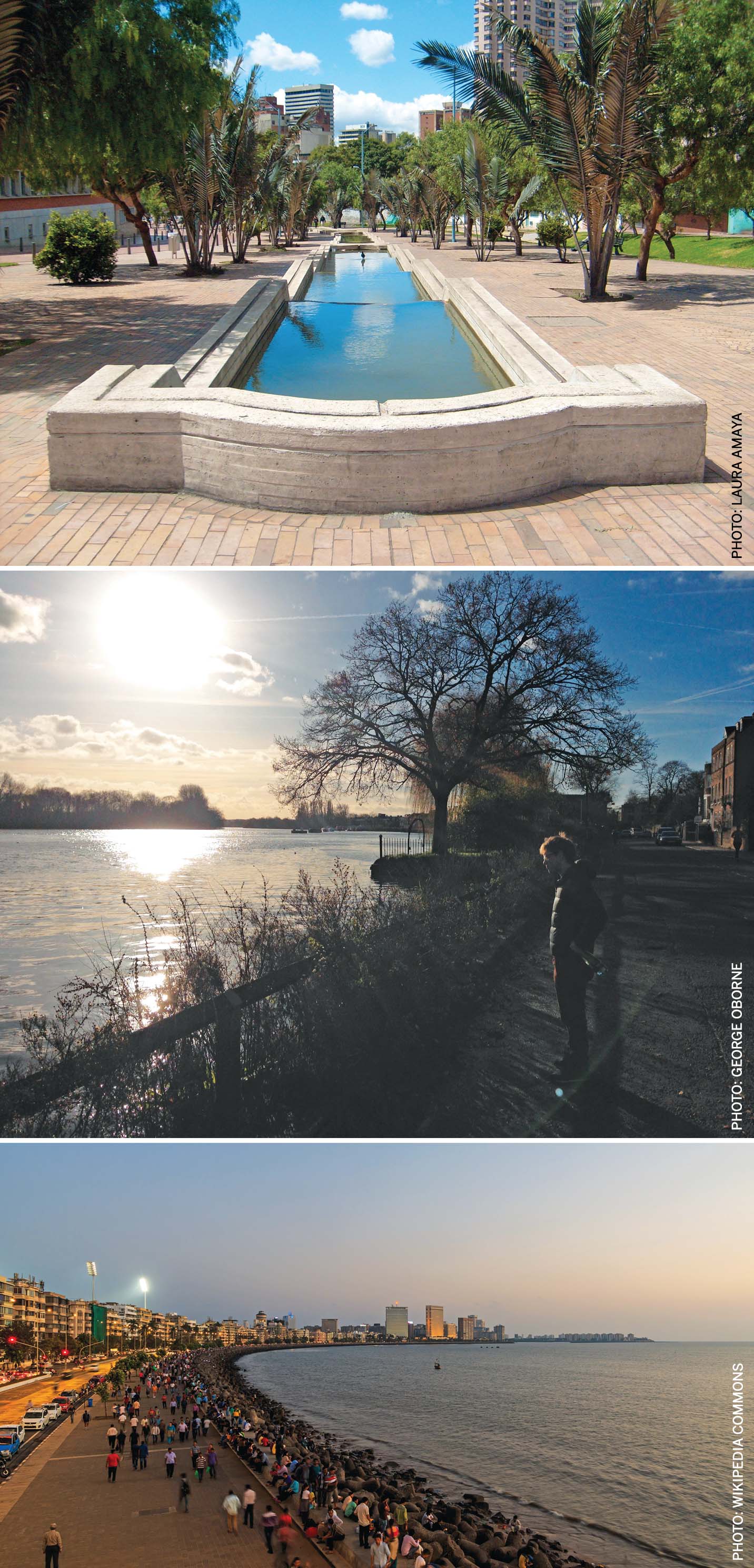

Middle: Thames river bank, London

Bottom: Marine Drive seaside promenade, Mumbai

Finding space for leisure

On the way home, a London commuter can sit on a bench under a tree, or stop at the local park for a breath of fresh air. Beyond small neighbourhood parks and squares, an additional 40,000 acres are covered by parks like Kensington Gardens and Regent’s Park, making up 9.6% of London’s total surface area. Hence, the average Londoner has greater access to mid-week leisure, along with a host of recreational alternatives to visit on days off.

Mr. Peñalosa’s conjecture that inequality is felt most during leisure time thus comes as no surprise. During his first term in office,

Mr. Peñalosa led the renovation of vast swathes of Bogotá. He envisioned a city where leisure was not confined to a few, isolated spaces. This meant creating ample room for walking, dedicated bicycle lanes and urban furniture that brought leisure into last mile commuting, much like in London. With TransMilenio also came the creation of parks across the city, particularly focused in and around marginalised neighbourhoods in the south of the city. These ranged from neighbourhood play parks to multi-acre green areas with sports and recreational facilities. Those with limited free time could now easily and affordably access spaces for leisure.

Both London and Bogotá have somewhere around 5,000 people per square kilometre, or roughly 5 people per square metre. By contrast, Mumbai has a density of 20,000 people per square kilometre; 20 people in a square metre means that people are, quite literally, stacked on top of one another. Mumbai, unsurprisingly, falls short of its projected demand for open spaces, as mandated by the city’s 2014-2034 draft Development Plan. Beyond areas like Colaba and Churchgate, sidewalks are an uncommon sight, and the ones that do exist are often obstructed by street vendors or make-shift homes. Thus, an average Mumbaikar spends most of their walking time fighting for space with cars, motorcycles and auto rickshaws.

London residents can walk into the British Museum during their lunch break for a glimpse of the Rosetta Stone or the Elgin Marbles

Of late, Mumbai has been making amends for its bad history with leisure spaces. Carter Road, a seaside promenade in the suburb of Bandra, opened to the public in the early 2000s and complements an increasingly consolidated network of sea-facing walkways that run from Juhu Beach and stretch 30 kilometres south to Nariman Point. The Matunga Flyover Garden, unveiled earlier in 2016, has also set a precedent for reclaiming residual space under elevated highways, often used for parking and garbage piling, as one for public leisure.

Yet despite these encouraging examples, most open spaces in the city are in upscale areas; such is the case with the Hanging Gardens on Malabar Hill or Shivaji Park in Dadar. The remaining open spaces tend to be private property, many of them Gymkhanas: exclusive member clubs. So, while cities like London reserve their best open spaces for the public (think Hyde Park), cities like Mumbai cordon off their prime real estate for golf clubs (Willingdon Club) or fee-only events (Mahalaxmi Racecourse).

Right: London

Having a place for leisure

Many of Mumbai’s spaces for leisure also become ‘places’ for leisure. Marine Drive, for example, fills up with hundreds of families for the firework celebrations around Diwali, the Festival of Lights. Similarly, Girgaum Chowpatty and Juhu Beach see thousands congregate for the immersion of statues of Lord Ganesh late in the monsoon season.

Yet, besides a handful of open spaces, Mumbai has very few dedicated places for leisure and only a fraction of them can be used by the public. The Taraporewala Aquarium is heaving with visitors on evenings and weekends, as are the Mumbai Zoo in Byculla and the iconic Gateway of India in Colaba. Policemen and security guards usher guests with whistles and threats, turning leisure into a time of hassle. Other venues like the Wankhede Cricket Stadium and the National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA) are not affordable to most. In a city starved for leisure, many families resort to the cinema, making Bollywood one of the biggest film industries in the world. Beyond this form of entertainment, culture and sports are largely reserved for a privileged few.

In contrast, most of London’s main museums and galleries are free and open to the public. London residents can walk into the British Museum during their lunch break for a glimpse of the Rosetta Stone or the Elgin Marbles. Parents can take children to the Science Museum or the National Maritime Museum, and instil in them curiosity for new subjects from an early age. Students and young couples can make their way to the Royal Opera House on weekends, with standing seats often available for under £10 (INR 860). Culture is open to all budgets and interests and therefore residents can thrive on multiple fronts.

Mumbai has very few dedicated places for leisure and only a fraction of them can be used by the public

Going to Wembley stadium or attending a tennis match at Wimbledon may not be within reach for most Londoners. However, the city’s infrastructure allows for residents to exercise during their leisure time. London’s Thames river bank and the Regent’s Canal are both excellent, car-free running circuits. Hackney Marshes alone plays host to 82 football and rugby fields and cricket pitches and is filled every weekend. London Olympic venues remain open, introducing the public to other sports like cycling, swimming and gymnastics.

Bogotá stands in the middle ground, having deliberately invested in leisure since the early 2000s. The Ciclovía cordons off major avenues for seven hours on weekends and holidays and makes them available exclusively to walkers, skaters and cyclists. Most public parks have sports courts and facilities and there are over 25 open-air exercise gyms around the city. Beyond that, several libraries around the city invite inhabitants to read or study anytime during the week. Bogotanos can also enjoy free theatre and musical performances during city-wide events like the Open Air Theatre Festival and Rock al Parque, which hosted over 240,000 people earlier in 2016.

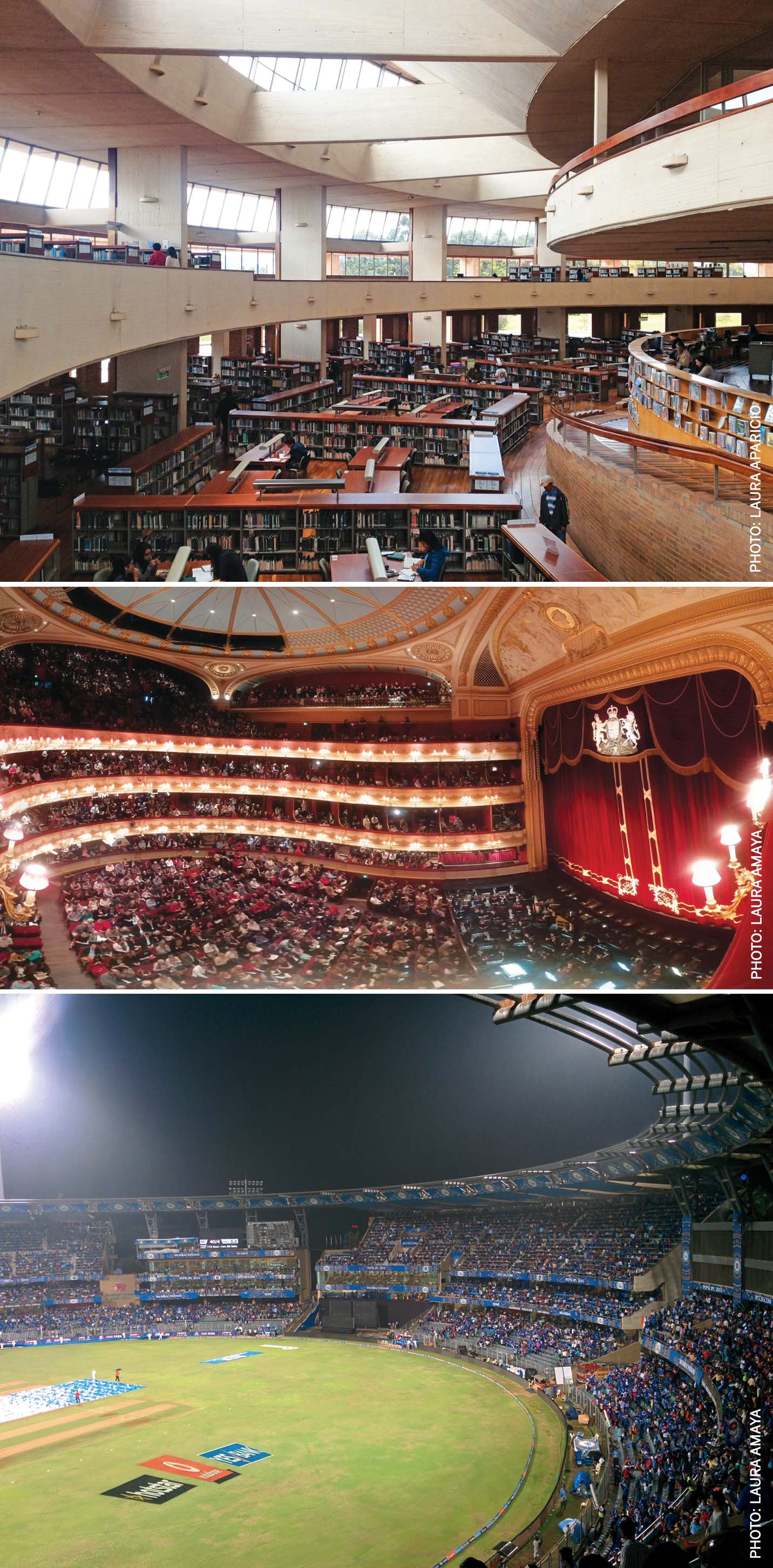

Middle: Royal Opera House, London

Bottom: Wankhede Cricket Stadium, Mumbai

Finding equity in leisure

The trend towards global urbanisation is intensifying the pressure on cities to deliver options for leisure that cater to the needs of multiple groups. Leisure permeates all aspects of daily life in a city, from commuting to weekend recreation. The luxury of open space, seamless transport and therefore greater equity in leisure is easily afforded to London. The UK’s GDP per capita is five times larger than Colombia’s and a whopping 28 times the size of India’s. However, urban development policies, such as those implemented by Enrique Peñalosa, may enhance equity and quality of life; Colombia now ranks 3rd, globally, in terms of ‘gross national happiness’. By giving people a greater number of safe, accessible and engaging spaces in which to enjoy a greater amount of leisure time, urban planners can narrow the gap between the rich and the poor.

Comments (0)