Through time and transformation, the traditional riverscape and its inherent ‘Indian-ness’ has gradually faded away. Distinct architecture that underlines the identity of these once vibrant cities is lost to misplaced aspirations and imported perceptions. Within this river landscape, the built inserts of ghats have reinforced the age old nature-culture, people-water liaison along the journey. How can the design of ghats serve to redeem the memory of traditional, contextually appropriate riverscapes in a landscape of anonymity today?

Indian Identity of Riverscapes

India’s historic cities were incredibly successful in developing distinct identities. Guided by geography and climate, limited local resources and individual history, riverscapes emerged as unique design expressions for each settlement. The holy river was central to their being.

Water was of utmost significance to these communities in their dincharya (daily life), traditions and festivities. Over time, riverbanks attracted temple complexes, pilgrimage sthans (sites), palaces, forts and capital cities through successive reigns and periods in history. Royal enclaves or hamlets together contributed to blending the natural flow and seasonality of river systems with the cultural calender of celebration and social structure of use and upkeep and finally emerged as strong visual expressions on Indian terrain.

Despite their iconic value in Indian ethos, riverscapes today send out a contradictory message

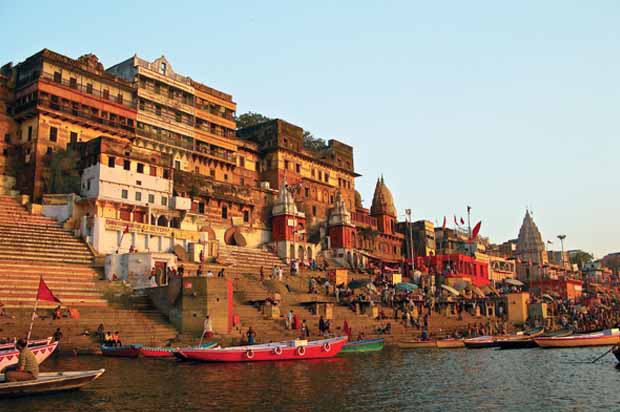

River cities such as those of Varanasi and Allahabad illustrate this exemplary connection between people and water, a permanent feature in the former and a transforming urbanscape in the latter.

In the instance of Varanasi, education, philosophy, culture, arts and religion flourished, fuelling daily rituals on one hand and enriching the urban form on the other. The Kumbh Mela at Allahabad, held once every 12 years on the banks of the River Ganga, has bestowed an undeniable socio-cultural value and a reaffirmation of a sense of community to the city despite its ephemerality.

Despite their iconic value in the Indian ethos, these riverscapes today send out a contradictory message. Not only is their visual identity being overtaken by nondescript architecture, the significance of the river in our spiritual and physical well-being is lost. A polluted river and a chaotic urbanscape are replacing the once respectful urbanscape in these cities. This in turn fuels trends in lesser known urban and rural settlements along the journey of the river.

The ghats have and must continue to perform a variety of complex religious, social and environmental functions in a limited space

Aspiration Versus Identity

City building in India has brought about an accelerated transformation in urban form, experience and liveability irreversibly altering the physical and cultural milieu. This change is a product of misled aspirations, changing needs of water access, sporadic migration and squatting at a local scale. Global level political upheavals, foreign occupation and climate change add their own twist to the tale. As cities move, expand and mutate, the connection between communities and water is getting further misplaced, leaving the historic and cultural identity of the Indian river city hanging by a slender thread.

The vital river-settlement interaction has gone missing as the focus of cities has shifted away from the river. From what began as the raison d’être of urbanisation has today been relegated to the background of civilisation. In Varanasi the ghats stand forsaken at the altar of overuse, misunderstood significance, lost amongst the ‘modern’ inserts of hotels looking over the murky water of the holy Ganges. While maintaining their purpose for religious ablutions, they also serve multiple needs.

The plight of urban iconic ghats is echoed further upstream and downstream in other cities, towns and villages located along the banks. The river is proving difficult to access, plagued with dumping grounds, dirt paths, dense ephemeral vegetation and populated by squatters. This conscious or unconscious turning away from the river by our planners has given birth to an urban habitat that has overwritten the historic identity of these settlements with architectural anarchy. The result is a cluttered, incoherent waterfront contrasting with enclaves of clean, well-maintained private environments that make up our cities today.

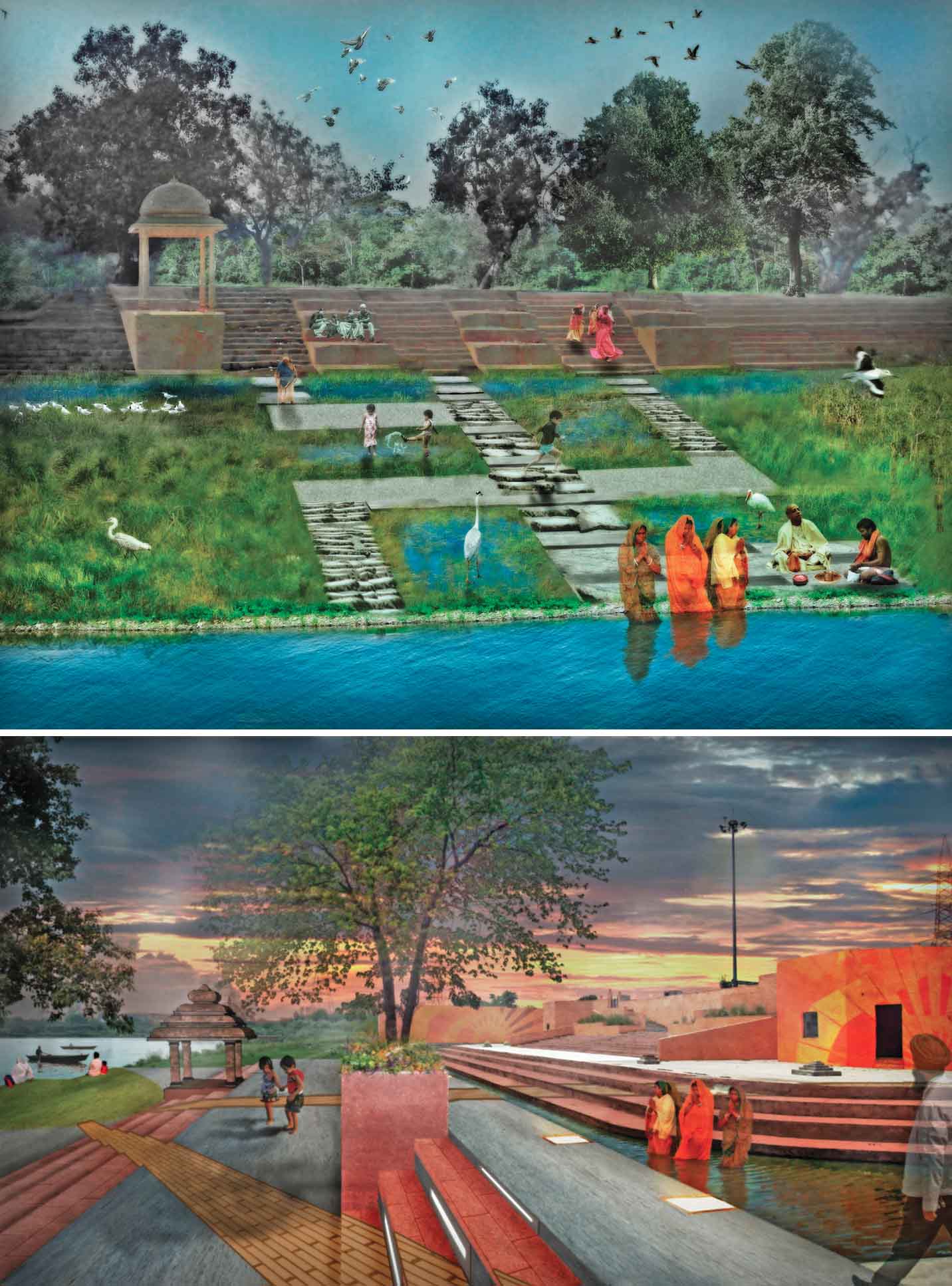

Bottom: Designing public access to riverbanks - A Ghat in Delhi, Concept View

Missing Link: Sensibilities of Design

Riverfronts in major international cities are often dominated by luxury apartments and upscale businesses. This is not relevant to most parts of India as the masses nurture associations rooted in a traditional socio-cultural context.

Riverfront projects such as the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project of Ahmedabad city have transformed cultural landscapes into unidentifiable urban commercial spaces. While they have imbued the city with a brand new identity, which itself is not a bad option, the chosen language does not build upon the traditional identity of Ahmedabad, which is now lost forever. Responsible design has to facilitate and reinforce identity in place of reinventing solutions. But in doing so, one should guard against complacency in viewing them as mere artefacts that need to be appreciated, as against their overall relationship with the natural rhythms of a river and the social fabric associated with it.

In the Indian ethos, a natural setting is more than just a setting of hills, rivers and forests. It is the canvas against which the Indian traditions and knowledge systems are conceived, practiced and celebrated. Enriching urban design with culture and tradition creates an aesthetic that is unique and specific to the diverse communties of the place. The real challenge is to design for this diversity respecting the need for retaining a tactile, inherently cultural experience, which these communities are familiar with, live in and encounter every day in their city.

Top: Concept Plan

Bottom: Concept View

Towards an ‘Indian’ Identity

As the late Charles Correa stated: “Identity is the trail left by civilisation as it moves through history.” The identity that communities living in these cities relate to is recorded as much in religious rites and rituals as they are in brick, stone and mortar. The issue of heritage/cultural identity versus urban identity is a strongly debated one as every architect, planner and policy maker has his/her own definition and there is little consistency across fields. We are faced with the conundrum of crafting an ‘Indian identity’, one that encompasses historic, cultural and contemporary layers. To revive the unique urban identity of Indian cities, one needs to look beyond the dichotomy of tradition and modernity and instead seek creative ways to engage the two.

River systems in the Indian context are metaphors of transcendence. Ghats symbolise the end of a journey. This is where time and space dissolve into an abyss of universality. This unique character of ghats integrates the abstract, intangible spirituality with the tangible aspects of ablution or cremation.

The real challenge is to design for this diversity respecting the need for retaining a tactile, inherently cultural experience

Rural, peri-urban and urban communities on rivers face a multitude of challenges ranging from poor water quality, obliteration of the river-city connection and a near absence of basic facilities. Merely developing waterfronts as ghats will not be successful if the water they are accessing is contaminated and unclean. The Swachh Ganga Research Laboratory in Varanasi, which conducts regular water quality tests, found that faecal coliform counts (FCC) ranging between 16,000 to 60,000 mpn per 100 ml of water from the bathing ghats, 50-100 times above the permissible limit (limit for bathing is 500 mpn per 100 ml as stipulated by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB).

This can be mitigated through the use of technology and innovation to manage water and solid waste pollution. Balanced with this futuristic vision is the rootedness of design in traditional thinking and a design vocabulary associated with a river landscape. Riverbank schemes that bridge the past, present and future can serve as a holistically designed repository of cultural heritage. Re-defining the future of contemporary river systems in India, these designed spaces have the potential to connect cultural associations with community aspirations.

The cultural and social activities associated with riverbanks are central to ghats. Traditional spatial design of ghats seeks to reinforce the relationship between the city and its inhabitants and visitors.

Bottom: Contemporary Ghats Inspired by Traditional Design - A Ghat in Uttarakhand (Concept View)

However, equally important are the functional aspects that lead to continuous use and long-term sustainability of such spaces. The ghats have and must continue to perform a variety of complex religious, social and environmental functions in a limited space. It is vital to create dynamic places that cater to an array of uses and users, both in a daily context, as well as seasonally during festivals thereby maintaining and even enhancing the cultural identity of our rivers.

The design philosophy should thus seek to revive authenticity in terms of experience and historic integrity, engage in local construction practices and materials like use of lime and stone work and maintain the visual and aesthetic experience of the ghats inspired by traditional elements and details. The true character of a city should be evident in public space revitalisation efforts on riverfronts for the people, of the people, by the people, creating an environment that reconnects the city with its lifeline.

As cities today seek to reclaim their riverfronts, a rare opportunity is offered to restore past glory and to create more sustainable communities. Cities like Delhi have a tremendous opportunity to direct riverfront revitalisation efforts that will weave rivers and the communities together. Design of ghats, as one approach, links the historic and sacred aspects of the river with the social interactions of communities. An adequate response to our rivers will define the contextual urban form of our settlements and in turn improve the quality of life that we offer to the city dwellers making Indian cities ‘liveable’.

Way Forward

The challenge for us lies in finding a design vocabulary emerging from the traditional and addressing inclusivity for our citizens. The ghats have endured over time to bridge the past with the present and facilitate a unique identity for the future. If designed contextually, ghats can act as unspoken communicators exhibiting the aesthetic sensibilities and traditional ethos of Indian cities; as they enable India to look to the future while preserving the memory of our rich past.

Beyond Built Pvt. Ltd. (BBPL) is working on ghat inserts in ten river basins in North India since 2014. They have received a Global CSR Water Award in the Design and Architecture category for this project with their Government PSU clients in 2017.

All photos: Nupur Prothi Khanna and Mohammad Husain

Comments (0)