The rise of car-centric cities

Throughout history, the available modes of transportation have driven area development. With the introduction of streetcars, cities developed along radial streets that extended outward from the city centre in a star-shaped layout. And when owning a car became the norm, urban sprawl developments started to prevail. Consequently, many cities gradually adapted from a primarily pedestrian-oriented environment to an auto-centric lifestyle, giving rise to a continuously growing demand for parking and road capacity. Government policy has largely facilitated this demand growth by providing for new infrastructure. And, as a result, between 30% and 60% of the public space in many cities is currently devoted to cars that, on average, are used only 5% of the time.

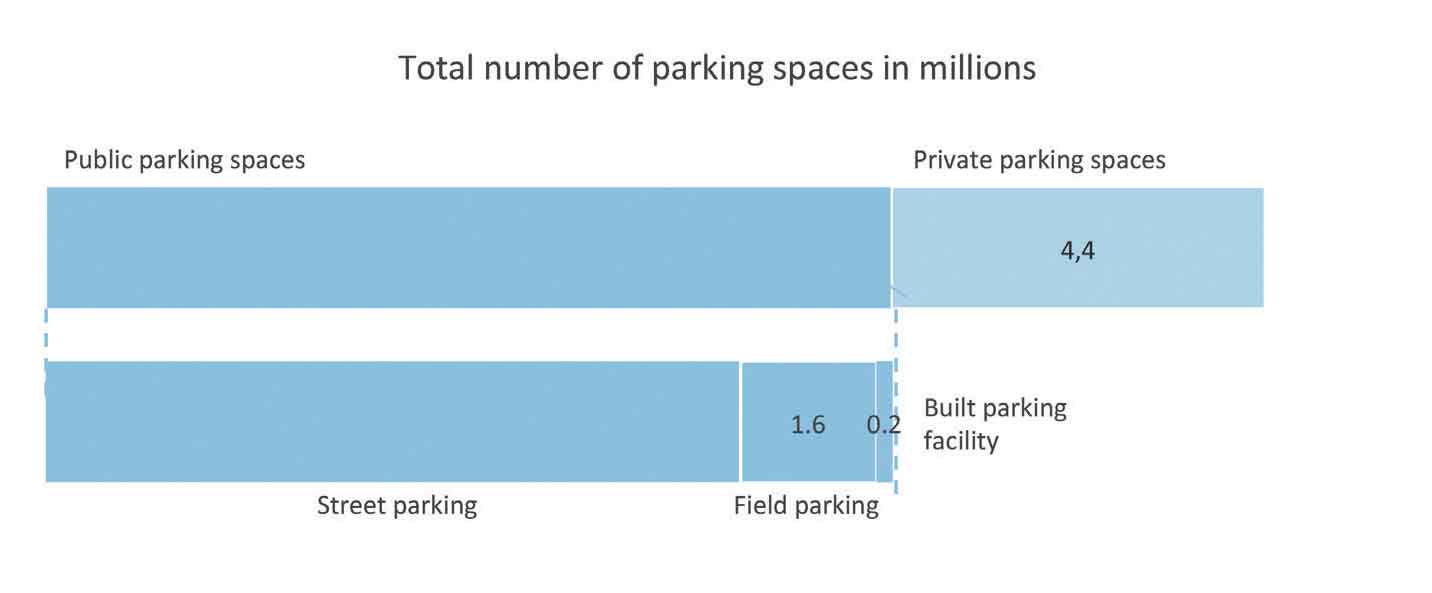

One of the main reasons that parking lots account for a significant share of the public space is that parking is generally regulated by governments. In most cities, governments do not only provide for parking on public land, but also set mandatory parking minimums for real estate developers on private land. As such they largely control both the supply of parking capacity and the parking rates, which are, especially for residents with a parking permit, often lower than the (land) costs of parking. In many cities the number of parking spaces is at least twice as large as the number of cars, while in American cities this number is estimated to be eight.

How car-centric developments have proven unsustainable

With ever expanding cities, our auto-centric lifestyle has posed challenges. As of today, the majority of the world population lives in cities and this share is gradually increasing. Many of these cities have now become so dense that adding more road and parking capacity has virtually become impossible, resulting in severe levels of traffic congestion and air pollution. Governments therefore aim to invest in alternative transport modes, while also increasingly discouraging car use through congestion pricing and higher parking fees. Yet, budgets for investments are often tight, while car discouraging measures are often very unpopular among (potential) voters. Many experts therefore claim that the answer lies in ‘smart mobility’ solutions. This raises the question: what is smart mobility and how can it be leveraged to transform the amount of land devoted to parking into space that improves the liveability of cities?

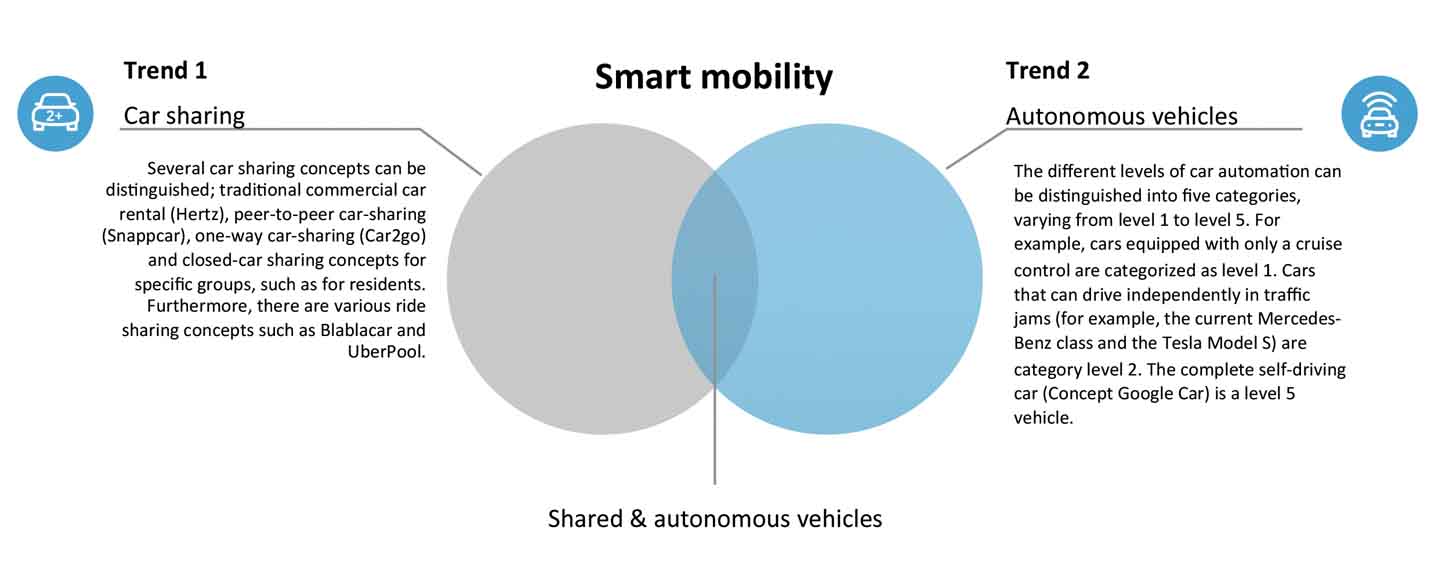

Most experts agree that smart mobility is about making mobility services more accessible and easy to use through the adoption of advanced software solutions with a particular emphasis on sustainable mobility means and modes. Two main drivers that are often highlighted when defining smart mobility are the rise of the sharing economy and the rise of autonomous vehicles.

As autonomous vehicles can eliminate driver costs, autonomous bus and taxi services could be offered much cheaper

The rise of the sharing economy

While both car and ride-sharing have existed as niche transport modes for a long time, a broad range of new vehicle-sharing concepts has been growing rapidly during the last few years as the digitalisation of the mobility sector enabled the rise of new business models, based on pay-as-you-use through digital platforms rather than on ownership. The arrival of on-demand ride services like Uber and Lyft, real-time ridesharing services such as Carma and Zimride, carsharing programmes such as Zipcar and car2go as well as bike sharing programmes are all changing how people get around.

Similarly, parking spots are also increasingly shared. Airbnb-like platforms enable real estate owners to rent out their parking spots to third parties. This provides opportunities to increase the occupancy rate of parking spaces. In mixed-use neighbourhoods companies can let out their parking lots to visitors and residents in the evenings and on weekends, while residents can make their parking spaces available during the day.

Experts expect the rise of these digital ‘mobility platforms’ to develop into a single integrated ‘Mobility-as-a-Service’ offering that integrates end-to-end trip planning, booking, electronic ticketing and payment services across all modes of transportation, public or private. Rather than having to locate, book and pay for each mode of transportation separately, Mobility-as-a-Service platforms let the users plan and book door-to-door trips using a single app. The hope and expectation is that this service will become so convenient for users to get around that they will opt to give up their personal vehicles for city commuting, not because they’re forced to, but because the alternative is more appealing.

The rise of autonomous vehicles

The rise of autonomous vehicles is the other driver of smart mobility that is expected to disrupt the mobility sector. As autonomous vehicles can eliminate driver costs, autonomous bus and taxi services could be offered much cheaper. In addition, the convenience of having a car parked right in front of the door, which is arguably the biggest advantage of owning a car, is less relevant when an autonomous vehicle is only one click away. It is therefore expected that in the future, fleets of autonomous vehicles will account for a large share of the kilometres travelled. Recently, several ride-sharing companies have already begun testing fleets of autonomous taxis, such as Uber in Pittsburg, while other companies, including automotive, have revealed similar ambitions. Consequently, the rise of autonomous vehicles offers ample opportunities to reduce car ownership in cities and thus, space devoted to parking.

Additionally, as cars are increasingly able to make use of advanced technologies that allow them to park autonomously, smaller parking spots could suffice in the future. After all, autonomous vehicles can be parked much closer to one another than conventional cars that require space for their drivers to exit and enter the car.

Transport experts expect that, in time, space savings ranging from an average of 25% and a maximum of 75% per parking space can be achieved. Furthermore, the location of parking becomes less relevant due to introduction of self-driving cars. As self-driving cars can park themselves, they can be parked at night on cheaper land outside the city. This frees up expensive parking spaces within the city. In short, the rise of autonomous cars provides great potential for freeing up parking spaces.

How much parking space could reasonably be expected to be freed up at what point in time?

The pace of the smart mobility transition

So it is clear that smart mobility provides opportunities to transform public parking spaces into other land-use types. The question that remains, however, is how much parking space could reasonably be expected to be freed up at what point in time? And what is the potential of this land?

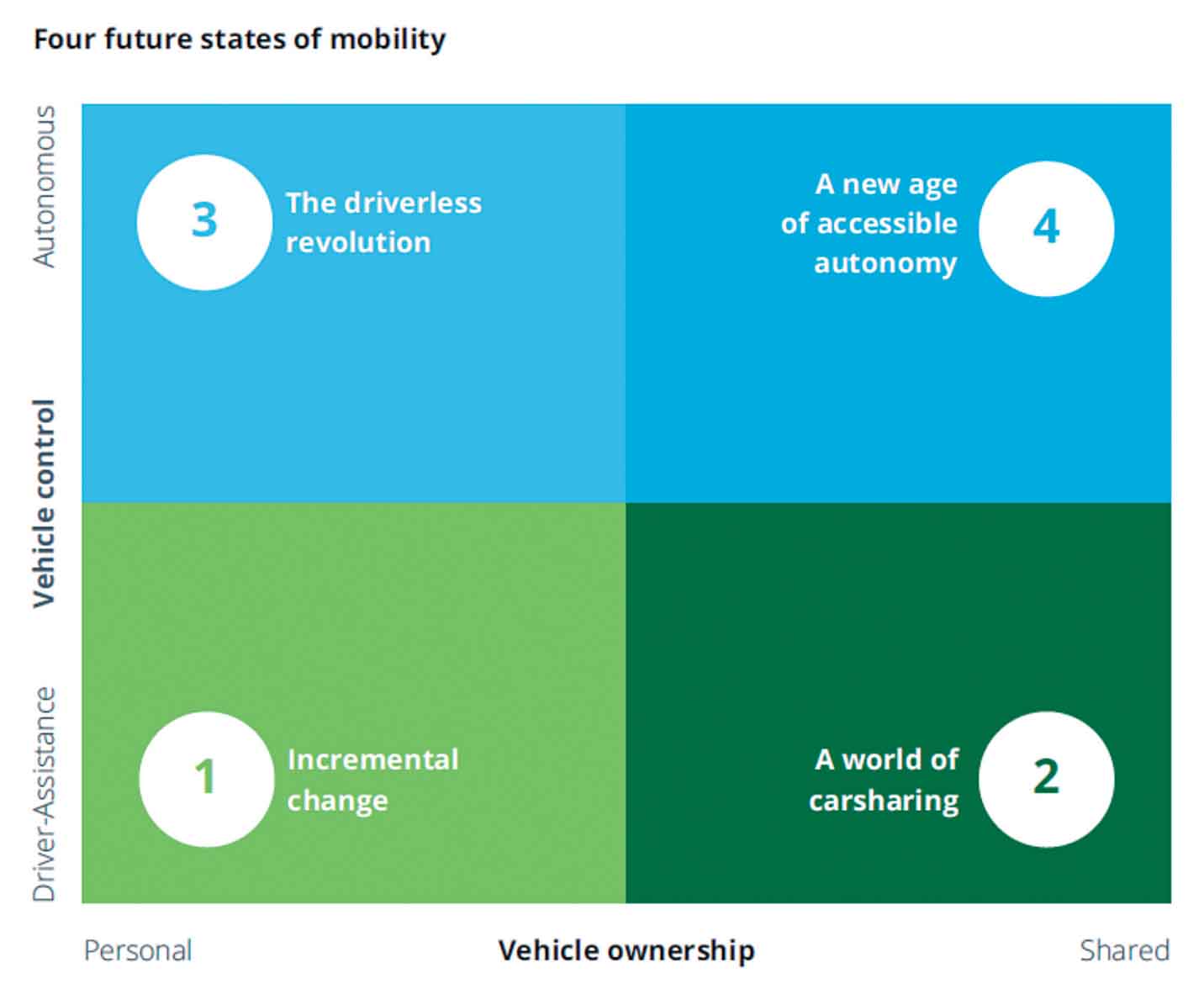

To assess this potential, Deloitte conducted a data analysis for the Dutch mobility sector, combining several public data sources on a national and a municipality level. Scenarios on four future mobility states were used to analyse the effects of smart mobility, as illustrated in the figure below. An important variable in these scenarios is the speed at which smart mobility concepts will be introduced in the Netherlands. The basis scenario assumes a prognosis by Deloitte University Press that was subsequently verified by different Dutch mobility experts. Based on the different scenarios, an estimate has been made of how much parking space can be freed up in the long term (2040).

The conclusion of the research (as per chart below) is that in the basis scenario, the total parking capacity could decrease from approximately 14 million at present, to approximately 9 million in 2040, which equals a decrease of almost 40%.

The potential of freed-up parking spaces

Subsequently, Deloitte assessed the potential to transform the freed-up land into new functions. Deloitte concluded that large-scale redevelopment projects in cities provide the largest potential for transforming parking capacity into real estate developments. Built parking facilities also provide opportunities for redevelopment, although to a smaller extent. Of the current Dutch parking capacity of approximately 14 million parking spaces, only a small share is housed in built parking facilities. In addition, the majority of these are underground, which makes the transformation possibilities limited.

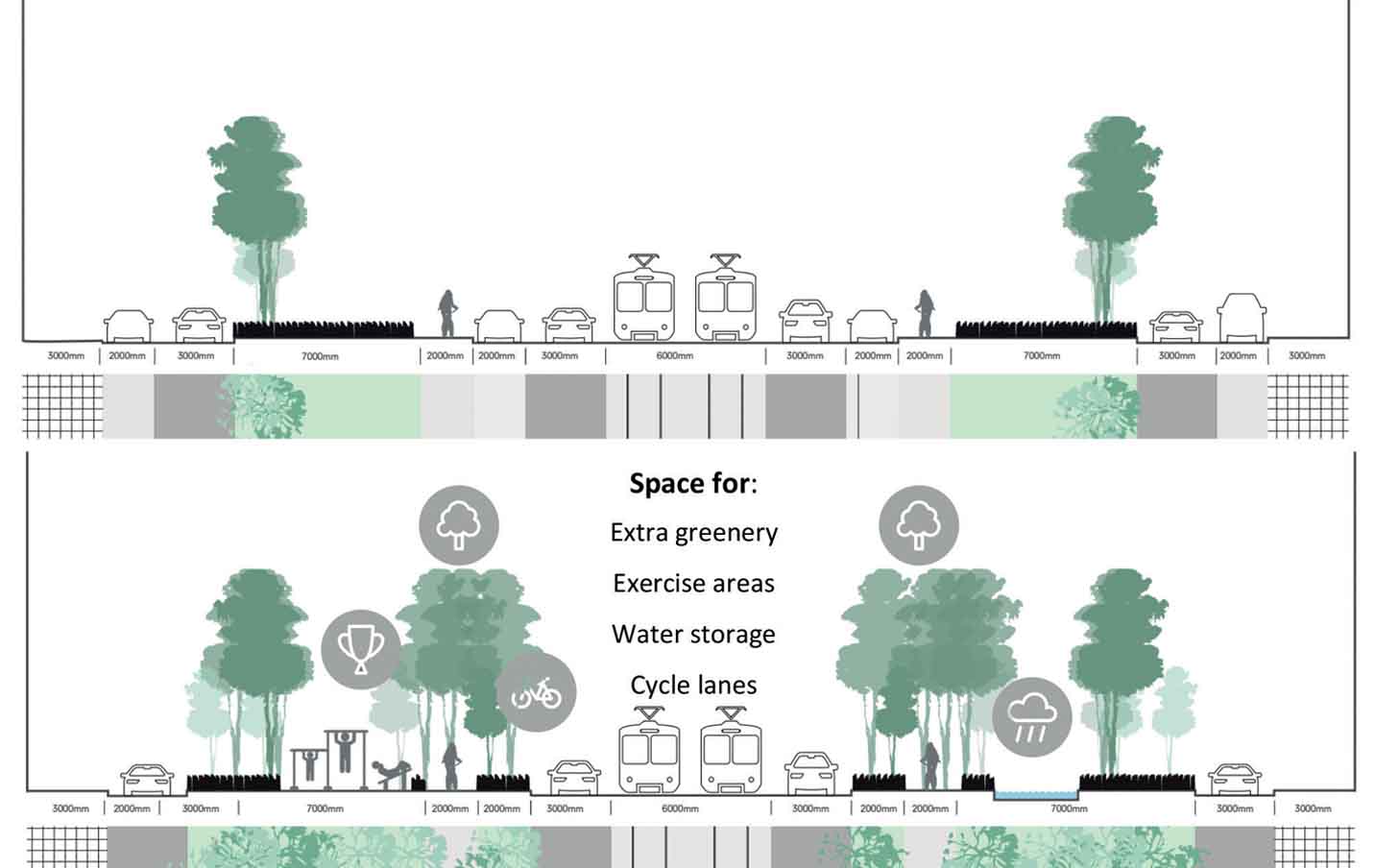

Deloitte concluded that a large share of the field parking is located in areas with low demand for real estate developments, while street parking areas generally do not have a footprint that allows for these developments. These areas could however be transformed in order to improve the quality of the public space and thus the liveability of the city.

All in all, Deloitte concluded that, in the basis scenario, approximately 45,000 new homes and 7,000 hectares of new public space, with the potential to fit 12 million trees, could be created on the ‘parking footprint’ by 2040. This could decrease housing shortages, while increasing the economic value of the city by facilitating an attractive environment for businesses and residents. The improvement of the public space will also result in healthier living conditions, as extra greenery will make the air cleaner and greenery reduces the chance of depression and other diseases. Furthermore, an improvement in the amount of green space results in positive feelings of social safety and improves the social cohesion. Finally, the freed up space by smart mobility can help to make a city more climate-proof. Extra greenery will result in more water storage capacity, more biodiversity and will help to decrease urban heat. To what extent these positive effects of smart mobility can be realised will strongly depend on the governance of the national and local governments.

So what can governments do?

Concluding, the potential of ‘smart mobility’ for freeing up parking spaces in cities is largely dependent on government (parking) policies. Parking demand has shown to be very elastic and parking supply and parking rates are therefore important determinants of modal choice and parking locations.

Parking policies should therefore be acknowledged as an important tool to influence modal choice and parking location and transport planning and spatial planning should be considered as an integrated challenge. Governments can set the preconditions for the success of smart mobility by restricting parking capacity growth and increasing parking rates, while at the same time facilitating alternative smart mobility developments.

Governments could start by building awareness of vehicle sharing as a less expensive alternative to car ownership. Additionally, providing (cheap) public parking spaces (with electric charging stations) for carshare vehicles and setting development requirements that support carsharing are crucial success factors.

All photos: Wouter de Wit

Comments (0)