Several years ago, I interviewed the then-mayor of Lancaster, California, who had made quite a splash by installing larger speakers along the city’s main commercial street, broadcasting bird song during the day. The mayor told me about its civilising effects and how it had led to a reduction in crime in the city. I never saw or scrutinised the data to confirm the effects but they made sense to me. I was troubled by the emphasis on the recording of bird song (not native species at that) and not the actual songs of birds, which would result from creating and maintaining the urban landscape as a bird habitat. But the effects reported by the mayor are consistent with my own impressions and personal experiences. And there is growing literature that demonstrates the benefits of birdsong.

We need more birdsong, indeed more birds, in cities. They are an essential element of our response to the modern conditions of loneliness and a partial antidote to the startlingly high levels of mental illness. The pandemic introduced many urban residents to birds, creating opportunities to notice and listen, sometimes for the first time, to birds and nature. I was asked by the host of a podcast during the first spring of the pandemic whether there were more birds and whether they were getting louder. There is some evidence that more of us have been buying bird feeders and bird seed, and watching and listening to birds more than we might have earlier. This is all very positive and one of the few silver linings in a time of great global distress.

Birds are an essential element of our response to the modern conditions of loneliness and mental illness

Birds are a magical presence in cities, and where their sounds and songs fill the spaces of a city, we are all better off. Indeed, we are likely to be better human beings. All forms of nature have these effects and a key premise of biophilia is that we have coevolved with nature and are happier and healthier when we have nature around us. We need nature as an essential element in our lives, not simply as an occasional experience on a holiday, but we need nature and the experience of contact with nature throughout the day; nature is not optional but absolutely essential to leading a meaningful and flourishing life.

And birds are a special form of nature in cities. The sights and sounds of birds, where they are abundant and present in cities, surround us. They provide moments of joy and delight as we see birds doing things, sometimes seemingly defying the laws of physics. They are the natural soundtrack of cities and provide animation and life to urban environments. They are unusually-ubiquitous inhabitants of urban species, reinforcing a three-dimensional experience of nature: they are above, below, all around us; we might see them perched on a tree, flying overhead, foraging on the ground. Birds in cities are a key ingredient (a secret sauce, I have sometimes said) in achieving the vision of immersive nature that we advocate in the emerging Biophilic Cities movement.1

Taking steps to make our cities bird-friendly will at once make them more sustainable, liveable and resilient

On a recent visit to the Belgian city of Leuven, I was treated to an evening spectacle of bird life there, specifically the aerobatic antics of the Common Swifts. Banking and streaming through the vertical spaces of the city, weaving at high speed in and out of human-occupied streets and laneways, it was at once remarkable flying and yet a common, if underappreciated scene in many cities. But these Common Swifts are a stand-in for most birds in the world today, facing a mix of serious threats including deforestation and loss of habitat, rising pesticide use and loss of flying insects, light pollution and, likely the largest threat of all, climate change. Cities can and must become part of the solution to these threats, creating safe urban habitats and becoming a voice and force for bird conservation globally.

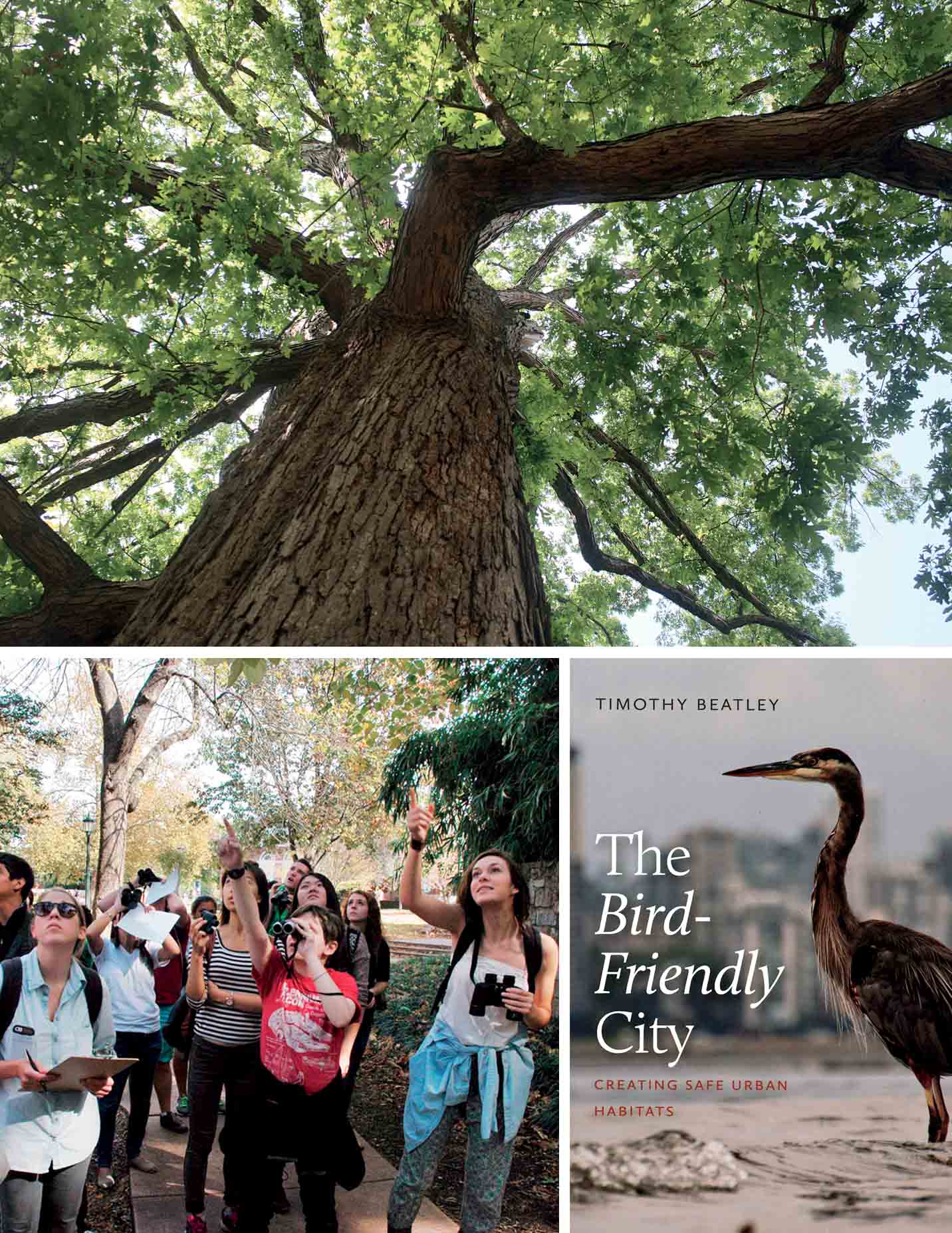

I am very interested in the idea of bird-friendly cities, and what it will take to design, plan and manage modern cities to ensure that people and birds thrive together. Our fates are intertwined in ways we mostly don’t recognise: What is good for birds is good for humans. This is the key message of my recent book The Bird-Friendly City: Creating Safe Urban Habitats (published by Island Press in 2020).2 Taking steps to make our cities bird-friendly will at once make them more sustainable, liveable and resilient, and will help us recognise that we have an ethical duty to respect and coexist with many other species.

Bottom: Birds also need water in cities. Shown here is the innovative urban wetland in Perth, Australia, converting a sterile water feature into a biodiverse native wetland

There are many dangers in cities for birds, of course, and we can take basic steps to ensure cities are safe places for them to live in and move through. In the US, upwards of a billion birds are killed each year from building and window strikes.3 Birds have difficulty seeing glass as a barrier (they see reflections of clouds and trees and other outside vegetation). The good news is that increasingly cities are adopting mandatory bird-safe building requirements. In 2020, New York City became the largest city to adopt such requirements, under its Local Law 15, which stipulates that new or renovated buildings in the city must install bird-safe windows (or in the parlance of the code, ‘bird friendly materials’) up to the first 75 feet above grade (where the dangers to birds is greatest).4 San Francisco and Toronto have adopted similar requirements and have been leaders in bird-safe design standards. And there are now many commercial products for treating and retrofitting building windows and facades to make them more visible to, and safe, for birds, such as feather-friendly dots and relatively inexpensive parachute cords that drape from above.

Making buildings more bird-safe will also make them more energy efficient and reduce their carbon emissions; important and necessary goals in many cities. The convention centre in New York famously replaced all its glass with bird-sage fritted glass, which led to an estimated 90% reduction in bird mortality and also a 24% reduction in energy consumption.

An interest in birds can become an important reason for socialising and a mechanism for building social capital in cities

Another serious threat to birds is urban light, especially disorienting and fatal during periods of peak migration when thousands of birds are often moving through and around cities at night (when most migration happens). Here, cities can work to turn off or minimise this lighting and there are a number of cities that are implementing some form of voluntary ‘lights-out’ programme. The City of Raleigh, North Carolina, has gone further, turning off all nonessential municipal lighting there (i.e. on municipal buildings and facilities) during peak migration. More generally, cities will need to rethink their approach to lighting, for birds and other nocturnal creatures sharing the spaces of cities, but also to reduce energy consumption and protect views of the night sky. A shift to dark sky lighting (e.g. full cutoff lights that shine down), is a big part of the answer but so also are efforts to minimise exterior lighting and to utilise motion-activated lights.

To maximise food sources for birds in cities we must radically rethink our urban landscaping practices, moving away from planting single-species turfgrass (and too frequently cutting) to managing more ecologically diverse landscapes, reduce or eliminate the use of pesticides and herbicides, and providing space and time for rewilding many parts of the city. The pandemic has led, in some places, to a new acceptance of more ecologically managed spaces (or at least a discussion about this) and more progress will be likely in many places, all to the benefit of birds. Parks like Brooklyn Bridge Park in New York City are now largely managed in ecological and bird-friendly ways, planting natives and restoring wetlands and habitat, keeping biomass on site and eliminating chemical pesticides (New York City banned them citywide in 2021).

There will be no birds, or very few birds, in cities without trees. And cities almost everywhere are doing a poor job maintaining and expanding tree canopy cover. Many cities lack a strong tree protection code that will protect especially existing older trees that do the most for birds, and that also provide the lion’s share of ecological services for humans, including urban cooling and carbon sequestration. Support for native species of trees is also essential. Doug Tallamy’s research on North American trees provides compelling evidence for the importance of planting natives. It is necessary to protect species (in my part of the world) like White Oak (Quercus alba) that hosts a remarkable number of native butterfly and moth species during their caterpillar life stage and provides most of the food needed to raise hungry chicks.5

The urban forests of many US cities, however, are populated by non-native species: Norfolk, Virginia, estimates that more than half its tree stock consists of crepe myrtles, a beautiful tree to be sure, but one that does not provide many benefits for birds. Protecting the trees and forest canopy that we have in cities is another essential step for birds, but unfortunately in many cities there are few regulations or restrictions and even when there are, they are often loosely enforced. Some cities like Washington, DC, do have strong protections especially for larger heritage trees with disproportionate benefits to birds (in this case through the DC Canopy Act), and recently, these have been strengthened.

Creating more bird-habitats in cities will require us to think about climate change in other ways as well. Hotter summer temperatures in cities will create many dangers for birds including the need for more sources of water. This will require moving beyond the practice of designing and installing ecologically sterile water features in cities. A needed shift to water that birds can drink and that provide habitat for birds (and many other creatures). One model example of this can be found in the City of Perth, in Western Australia, where a sterile, chlorinated water feature has been converted into a biodiverse native wetland.6

Ecological restoration is becoming an important goal in many cities, and the vision of regenerative cities that repair and restore ecosystems and biodiversity is also taking hold in many places. The examples are many: In Vitoria-Gasteiz, in Spain, they have converted a former municipal airport back to Ramsar wetland habitat, a part of the city’s impressive green belt, and a place I have had the pleasure of visiting several times. Many species benefit, including birds, and now nesting storks are returning. A more recent example is the Turkish coastal city of Izmir, where efforts are underway to convert a hardedge shoreline to a new park and habitat for Flamingoes.

Protecting larger blocks of forests and undeveloped land in and around cities is an important strategy. Larger, connected networks of habitats that allow birds to move safely in and around cities will be essential. Many cities are working to create ecological corridors that will connect these larger habitats and parks, and will also bring more birds and nature into urbanised areas of cities. One example of this is the approach taken in the Colombian city of Medellin, where new trees and vegetation have been planted along 20-kilometres of major streets, creating a series of ecological corridors. This has already brought many birds back into the city, and created shaded movement corridors for pedestrians and bicyclists. One main purpose is to provide shade and cooling benefits to cities.

Ecological connectivity will be an essential quality and condition for bird-friendly cities of the future. Edmonton, Canada, is an example of a city that has given priority to ecological connectivity in its planning, utilising tools like circuit-scape modeling to visualise and understand the city ‘through the eyes of a chickadee’. Where there are ecological disconnections and discontinuities that

impede a chickadee’s (or any bird’s) movement through the city. And Edmonton has been installing wildlife crossings in many places, numbering some 35 now, many that will benefit birds as well.

We can also reimagine (and redesign) buildings and urban infrastructure with birds in mind. In the UK, the country’s largest homebuilder, Barratt, has declared that all future projects will be wildlife-friendly and projects like Kinsbrook (near Aylesbury) has been integrating nesting boxes for Swifts (so-called swift bricks) into the sides of new homes. Some prospective homebuyers are even enthusiastically selecting the homes because of the birds and wildlife, though more education and active participation around bird-friendly buildings and projects is needed in most cities. More can be done to redesign rooftops, facades, courtyards and the many surfaces and spaces around buildings as habitats for birds.

There is a lesson from the pandemic, the respite from cars allowed residents to hear sounds of nature they had never heard before

Radical shifts in the mobility patterns in cities offer more room and habitat for trees and birds. And reducing the dependence on noisy fossil fuel powered cars and trucks, also offers the prospect of hearing birds in ways we haven’t before. Again, there is a lesson here from the pandemic, as the brief respite from cars allowed many residents to hear sounds of nature they had never heard before.

I argue in The Bird-Friendly City that we ought to consider judging the goodness of a city by the extent of its birdsong, and that our goal should be that every resident, in every neighbourhood, be able to hear abundant native birdsong. That birdsong and other sounds of nature are a positive asset to a city is a mostly foreign notion in the world of urban planning. We spend much time (as we should) worrying about noise (which has severe negative implications on public health) and taking steps to curtail it but equally true is that we should cherish the natural sounds of a city, as a positive asset, that enhances health and wellbeing and connects us to land and nature in ways that we especially need today.7

Bottom Left: Cities can do a better job educating residents about birds and providing opportunities to engage directly with birds, such as through bird walks like the one shown here.

Bottom Right: Cover of The Bird-Friendly City book, published by Island Press in 2020

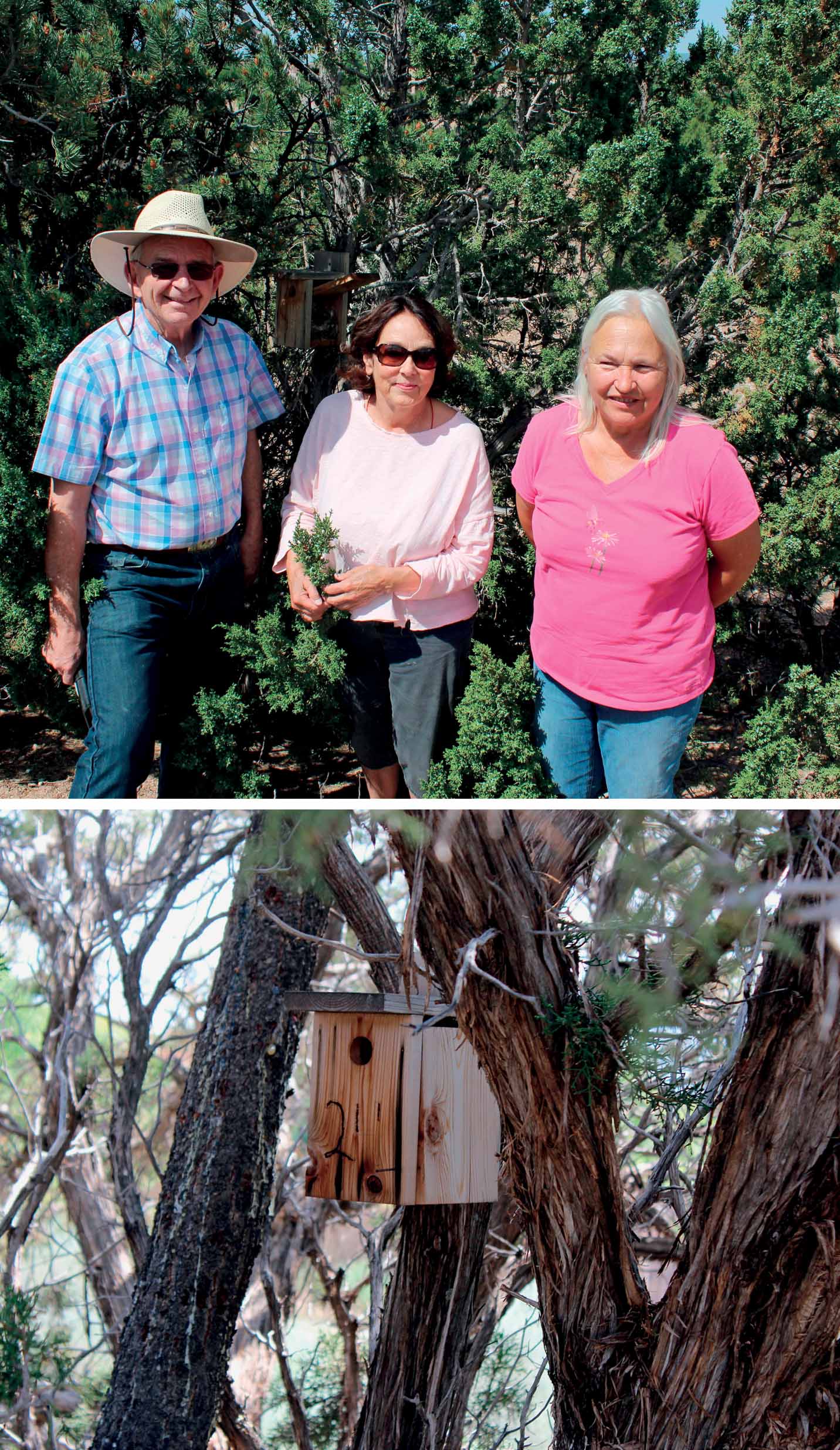

There are many other ways that cities can be designed, planned and managed to reflect a love for birds and these steps will help to address many other urban challenges, such as the worrisome increase in social isolation and in levels of depression. An interest in birds can become an important reason for socialising and a mechanism for building social capital in cities. In the process of writing The Bird-Friendly City, I discovered some inspiring examples of communities that have come together around birds. In the community of Aldea, for instance, near the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, residents have got together to monitor and care for one bird species in particular: The Juniper Titmouse (Baeolophus ridgwayi). It is clear that monitoring nest boxes and collaborating in the conservation and caring for birds is a powerful mechanism for forming friendships and social bonds and, in short, building community. A love of birds becomes an avenue for imparting more meaning to life and in the process for deeper connections and caring between and among the human occupants of a city. And cities can find other creative ways to teach about and connect residents to the birds around them, including school-based programmes and city-sponsored bird walks and bird classes.

Cities can also help to support the emergence of citizen-based activism and conservation around birds. Organisations like Portland (Oregon) Audubon and New York City Audubon, have become important advocates and conversation partners. The organisation FLAP (Fatal Light Awareness Program) in Toronto has been effective in raising awareness about bird safety and enlists an army of citizen-birders during peak migration to monitor bird-building collisions and to rescue injured birds. In addition to its native birdsong, a city’s goodness and moral metal might also be judged by the number of people who actively care about birds and work on their behalf.

My hope is that cities give birds more explicit attention and importance in their planning and management decisions. Any casual review of city comprehensive plans, for instance, will find few, if any, references to birds. They’re not a high priority for most city planners or managers, though I believe they should be. Just as we have created new positions in cities to reflect the importance of key challenges like urban heat and resilience (e.g., appointing a Chief Resilience Officer, and more recently the position of Chief Heat Officer), similarly, we should consider creating the post of Chief Bird Officer.

“Attention is the beginning of devotion,” observed American poet Mary Oliver. As a first step in many cities, we need a radical shift in our mindset about birds, from indifference at best, to one that views birds as cohabitants of cities and perhaps eventually as citizens sharing an equal right to exist and flourish. Then we might be close to reaching the true potential and promise of a bird-friendly city.

REFERENCES:

- For more about the Biophilic Cities Network see: https://www.biophiliccities.org/

- For more information about this book, see: https://islandpress.org/books/bird-friendly-city

- See Scott R. Loss, Tom Will, Sara S.Loss, and Peter P. Marra, “Bird–building collisions in the United States: Estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability,” BioOne, January 2014, found here: https://bioone.org/journals/the-condor/volume-116/issue-1/CONDOR-13-090.1/Birdbuilding-collisions-in-the-United-States--Estimates-of-annual/10.1650/CONDOR-13-090.1.full

- More specifics about this can be found in New York Department of Buildings, Bird Friendly Building Design and Construction Requirements Guidance Document, November 2020.

- Douglas W. Tallamy, Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard, Timber Press, 2020.

- See a film about this story here: https://www.biophiliccities.org/perth-urban-wetland-film

- For more about natural sounds as assets to a city, see Beatley, “Celebrating the Natural Soundscapes of Cities,” The Nature of Cities, found here: https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2013/01/13/celebrating-the-natural-soundscapes-of-cities/

All photos: Timothy Beatley

Comments (0)