The listing of industrial property as heritage sites seems to be a trend. It can be in the form of industrial machinery, factory buildings or connecting infrastructure. However, complete settlements and historic urban cores are also perceived as the physical remains of an industrial past. Most of these listed settlements lost their economic base once the industry left and many are in dire straits today. A fresh perspective on this is badly needed. Becoming a tourist destination – another trend in heritage conservation – seems an attractive way out. Meanwhile, we may observe that becoming a tourist destination also has a flip side: it may obstruct alternative, sometimes more promising developments.

Sawahlunto, built as a facility for a mining company, is the first industrial site listed as a world heritage property in Indonesia. In recent years, following the closure of mining activities, the challenge Sawahlunto faces is to once again function as a vital city. In its struggle to find a balance between tourist developments and alternative developments, the city seems to be setting an example for the world.

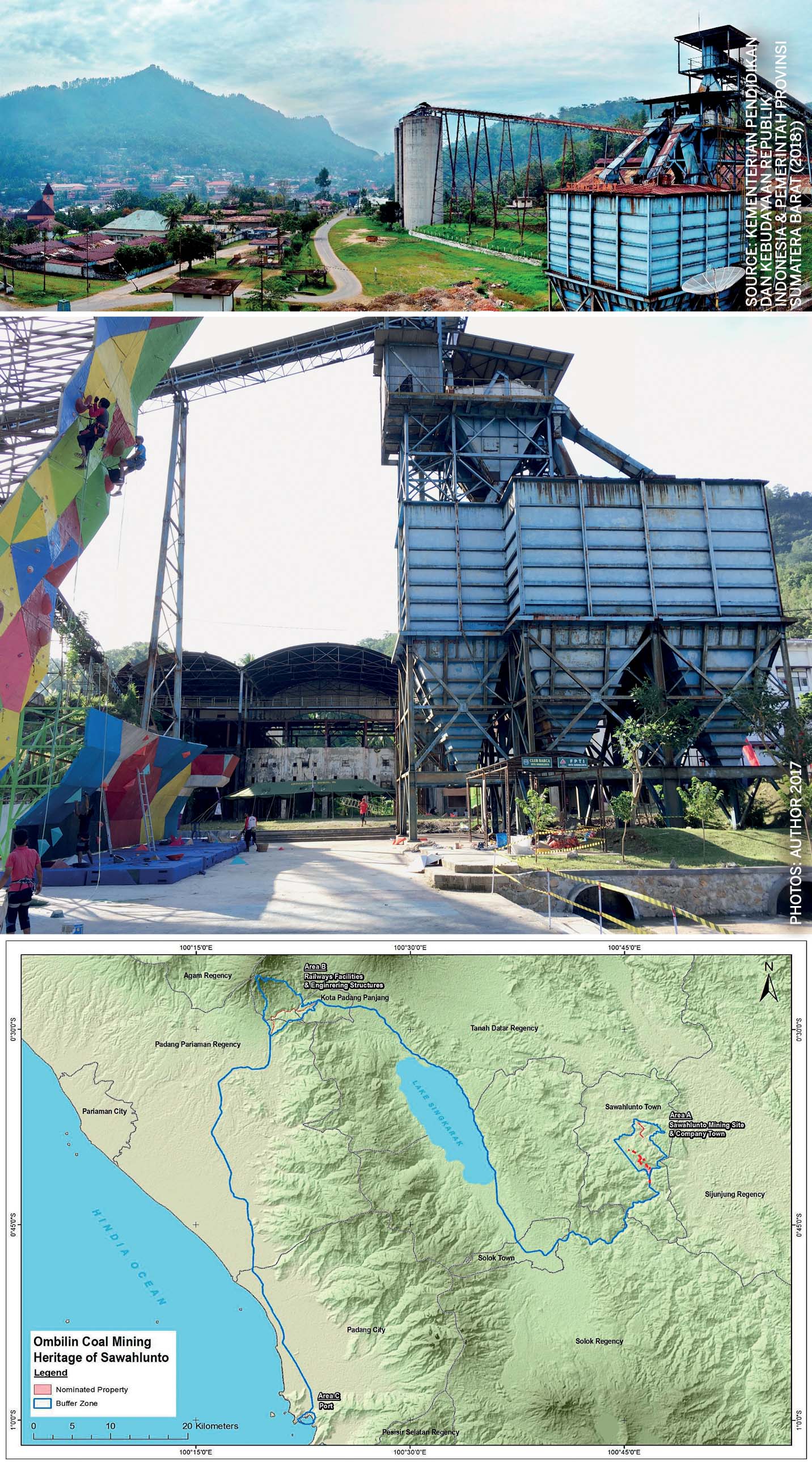

Right: St. Barbara Church - St. Barbara Church in Sawahlunto is a cultural heritage building as well as an attribute of the Sawahlunto Ombilin Coal Mining Heritage which is still in use. This church was inaugurated in 1920 and is currently managed by the Sawahlunto Parish. From the front of this church, one can see the Sawahlunto Hospital |

The tourist traps

Today, around the globe, people are manifesting a growing interest in history. This does not only concern major events like World War II, Colonialism or Slavery, but also local histories and private genealogy, which are growing in popularity. This is evident in the number of books published, movies screened or documentaries created on the subject; museums on the subject are flourishing like never before. The reason may be embedded in the spirit of the post-modern times we live in. The future-oriented nature of modernist times seems to have been replaced by a retrospective attitude while we move from one era to another.

It is this same retrospective mindset that explains a growing awareness of the built heritage and the historic city. There will be no country left in the world without an extensive list of protected heritage sites. On a global scale, UNESCO has listed over 300 World Heritage Cities. Conserving living cities implies, however, moving beyond the cultural dimension and looking into the societal dimension. We now know that heritage can be turned from a burdening problem to an economic asset. Heritage has been successfully deployed to strategically support many inner-city regeneration processes. Meanwhile, many historic cities have also been transformed into tourist attractions, fuelled by the promise of economic prosperity, that in turn would provide social leverage. A promising prospective!

Yet, as we may observe today, the promising tourist also has a flipside. We all know the examples. Venice being one of them. Here the residents of the splendid city are gradually being replaced by an ever-growing number of visitors, wandering through its marvellous urban core and wondering about its poignant history. Rising real estate prices result in gentrification and displacement of lower income groups. The city is no longer a place to live, but rather a décor piece, serving the visitor, not the resident.

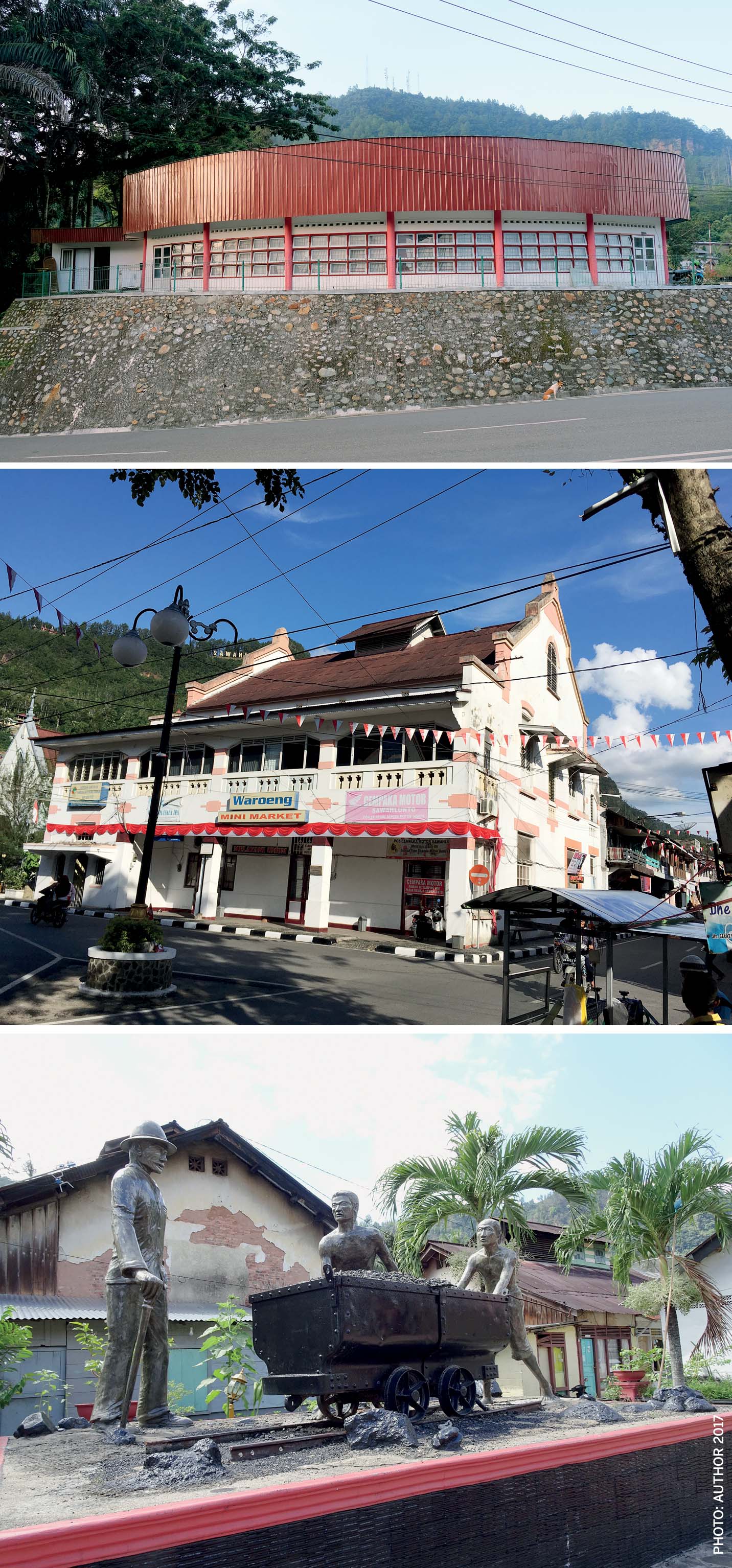

Right: Headquarters of the Bukit Asam Mining Company - The main office of the Bukit Asam Company is an old building owned by a coal mining state-owned company, namely PT Bukit Asam Tbk. Built in 1916, this building has a Dutch architectural style and has become the main tourist icon of Sawahlunto. The owner has a plan to use it as a hotel, but this has not yet been implemented. Meanwhile, the converted public space in front of the building is always swarming with people

The city of Galle in Sri Lanka is another example. Being an important trading port, the city was fortified in the 17th century and flourished thereafter. For its outstanding features, the city was listed as a world heritage property by UNESCO in 1988. Now that the fortified peninsula is easy to reach by car from the capital city Colombo, it is favoured by new inhabitants, coming from all over the country and even from abroad. As a result, not only are residents moving out of the historic city, but public services and common facilities are also being replaced. Thus, there is no more reason for the inhabitants of Galle to visit their own city centre. The urban core tends to be no longer the place where new culture is being produced, only a place where old culture is being reproduced.

Another example is Stone Town in Zanzibar. The former fisheries settlement grew to a wealthy city of structures built in stone only after the Sultan of Oman relocated his seat there in the 1830s. Today, the growing number of tourists visiting the fabulous spice island and its urbanised city stimulate economic activity. Yet we may wonder to what extent it serves the local community. How much of the profits flow to the travel sites, the beer companies or the fast-food chains of this world? And what about the jobs created? Many of them are in serving tourists, including washing their dishes. Did it bring the social leverage so urgently required? And, what is more, the Covid-pandemic showed how vulnerable these cities become, once they are monofunctionally developed for tourists.

Venice is no longer a place to live, but rather a décor piece, serving the visitor, not the resident

So, there is reason to take a critical look at heritage tourism. Tourism need not always be the best option for heritage and, inversely, heritage need not necessarily be the best solution for tourism. Using the tourist potential of the heritage city may exclude other potential uses. On the other hand, investments in non-heritage tourism outside the historic city may bring more financial and economic profit. The ambiguous attempts to find a way out of the dilemma that was not willingly created seem to be caught in the tourist discourse.

Programmes, as for example the ones offered by UNESCO, all deal with mitigating the negative effects of tourism, promoting sustainable tourism or facilitating responsible tourism. It seems as if we have lost the ability to think of heritage beyond tourism. Yet, the way out of the dilemma may be in using the development potentials that pose an alternative for tourism. The case of Sawahlunto shows an appealing example.

Middle: Former coal bunkers, now used by the regional Alpinist Club

Bottom: Map of Ombilin Coal mining heritage of Sawahlunto

An alternative approach: Sawahlunto

Located in the Indonesian province of Sumatera Barat, Sawahlunto lies in a valley of the mountainous Ombilin region. The city, some 90 kilometres North of the capital city of Padang, covers a total area of 274,45 km2 and has a population of ca. 65,524 inhabitants. The name of the place is a contraction of ‘sawah’, meaning rice field and ‘lunto’, meaning river. The two syllables refer to rice fields located in a valley that is fed by a tributary called Batang Lunto. The tributary originates in the valley of the hills, then flows into Nagari Lunto where Sawahlunto is located and continues to irrigate the rice fields. Notwithstanding the rural origin of the place, its modern history is associated with the coal mining industry.

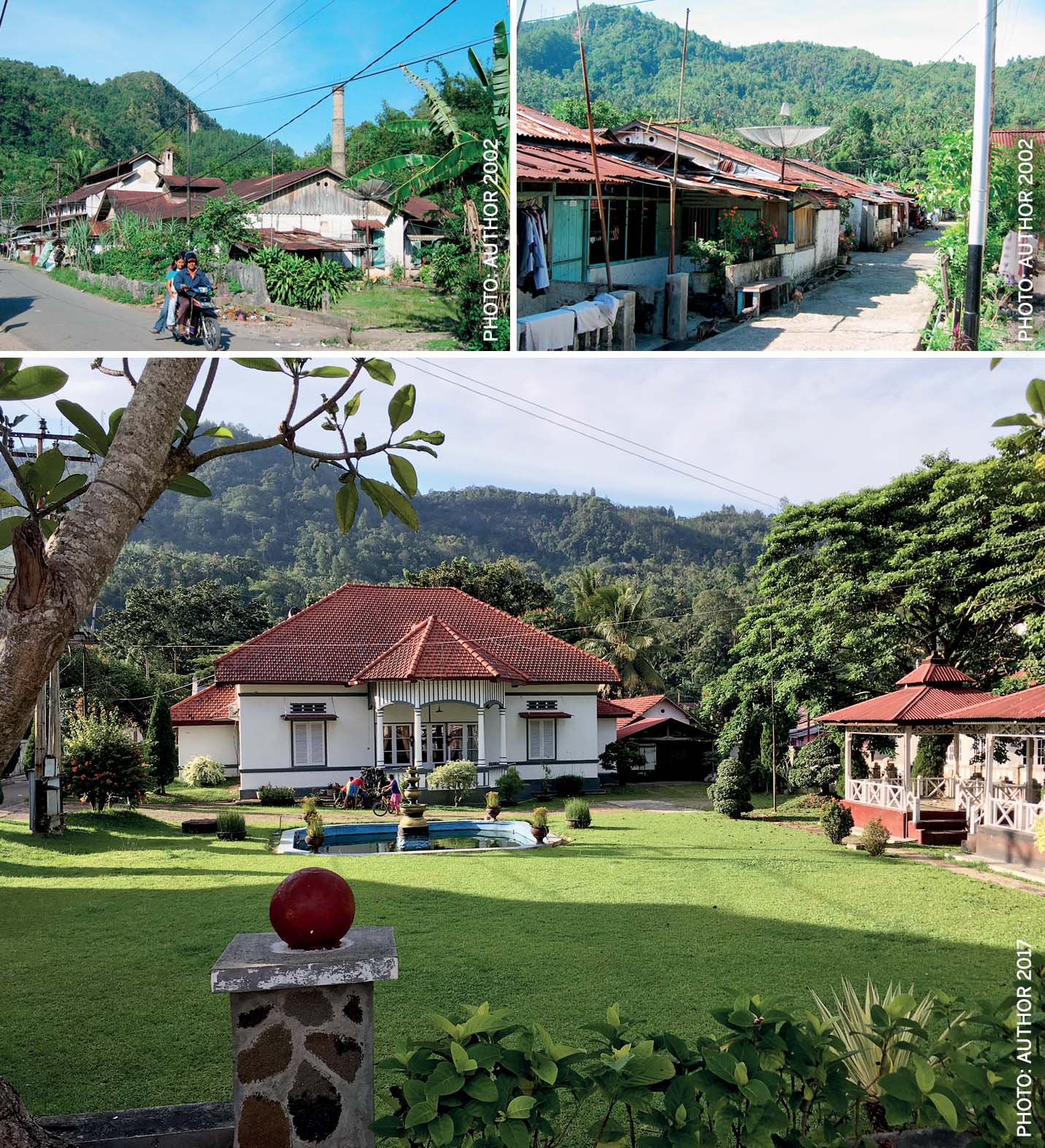

This mining history of Sawahlunto began under Dutch colonial rule. In 1868, huge coal deposits were explored in the flow of the Batang Ombilin. Due to the challenging geographical conditions however, it took till the end of the 19th century before the first coal could be extracted, processed and transported. From the start of the 20th century, the Ombilin coal found its way around the world. Soon, the Ombilin coal mine became one of the world’s main suppliers of carbon energy. Due to its remote location, a completely new town had to be constructed, containing all facilities and services a working community needed. As a company town, Sawahlunto was equipped with a number of advanced facilities for recreation, social events, religion, education and medical care. And next to that, a well-equipped prison was constructed to contain the forced labour employed in the mine pits.

After Indonesia gained independence following World War II, the Ombilin coal mines continued to operate through a State-Owned Enterprise, recently named PT Bukit Asam. By the end of the 20th century, the coal pits in and around Sawahlunto were so far exhausted that extraction on an industrial scale was no longer profitable. When coal extraction ended, the city’s economic base faded, people moved out and living conditions dramatically deteriorated. Since 2003, the Municipality of Sawahlunto has been urgently looking for a way out of the social crisis by initiating new economic developments. Based on the recommendation from ITB (Institut Teknologi Bandung), one of the leading universities in Indonesia, Sawahlunto established the road map for transformation from a mining city into a cultural city.

Top Right: Housing complex for coalmine workers

Bottom: Former director’s villa, now a guest house

Thus, Sawahlunto’s challenge of rehabilitation was expected to be met by deploying its tourist potential. With the support of the Central Government, the Municipality invested in reusing vacant mining structures and facilities for museum use. The former kitchen complex, for example, was converted into a museum facility. Also, a Railway Museum was erected. And one of the former mining tunnels was opened up for visitors. Tourist accommodations and facilities were created. Regular events are being organised, such as the International Songket Silungkang Carnival and the Sawahlunto International Music Festival. The strategy was supported by nominating the city as a world heritage property by UNESCO, based on its outstanding universal values. The daring nomination was granted in 2019. As a result of a skilful municipal strategy, living conditions improved and population numbers gradually increased.

Heritage has been successfully deployed to strategically support many inner-city regeneration processes

Notwithstanding Sawahlunto’s success, the awareness of its vulnerability grew. Replacing the mono-functionality for this new use might bring the city to peril. A possible threat that turned out to be all too real in 2020 during the Covid pandemic, which caused lockdowns around the world and visitors disappearing from Sawahlunto. Recreating a vital and resilient city requires a more diverse social stratification than the tourist sector alone can offer. What other labour force could be employed in Sawahlunto to provide a solid base of existence for its historic features? And how can you make sure the local community will develop culturally; based on its history without being trapped by this history?

For that reason, the Municipality of Sawahlunto investigated alternative ways in which the heritage assets could be a driving force for its development. Research was conducted in 2019 and was supported by the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands. It identified two alternative development potentials over tourism: expansion of the medical sector and rehabilitation of the former mining school. Both development potentials are currently being further investigated. Given the limited space in the narrow valley of Sawahlunto, expansion of these developments might mean halting the tourist development.

Middle: Former soup kitchen, now converted into a museum

Bottom: Hospital premises

Middle: Former miners’ buying cooperative building

Bottom: Mining museum of Sawahlunto

Current urgency for energy transition requires new research and education that could build upon famous energy knowledge in Sawahlunto, based on its mining history. Its development is in the hands of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. Sawahlunto’s Hospital, dating from 1915 has a renowned reputation, which is also rooted in the city’s mining history. As pointed out in the nomination dossier for world heritage listing, the hospital is one of the attributes demonstrating the site’s outstanding universal value. Expansion of medical services meets the current needs of the city, but requires optimising the utilisation of its limited space.

In 2014, a development masterplan for the extension of the hospital facilities was prepared. An additional building for an Emergency Room and Radiology Room were needed to accommodate a growing number of patients. The challenge of the design task was to find the right place and proper composition for the new building in the layout of the hospital and at the same time to upgrade existing buildings. As an attribute, the design process was carefully conducted to ensure the protection of old buildings. The workshop was conducted in 2023 with support from Dutch experts and architects. The heritage value is not only conveyed by the buildings, but also by the spatial quality. The hospital has specific spatial features, setting the principle for an additional building. The design solution is not focused on the buildings as individual objects but also by the possibility to give new meaning to the city. The proposal makes the heritage buildings visible and is a positive outlook for the city’s past.

Conclusion

The case of Sawahlunto shows tourism is not the only possible option for revitalising the historic urban landscape. Tourism is one means out of many to provide a future base of existence to the heritage we cherish. Where and when this tourism is serving the goal, it should of course not be excluded. Yet, our current preoccupation with tourism seems to hinder our search for alternative developments. At this point in time there is an urgent need to look beyond the tourist potential. It is no longer about mitigating the failures of tourism but rather about defining the alternative development potentials.

Bibliography

•Cheris, R. (2014) ‘Perencanaan konservasi kawasan ekspermukiman buruh tambang batubara di Kota Sawahlunto Sumatera Barat’, Jurnal Arsitektur Melayu dan Lingkungan, 1(2), pp. 57–75.

• Gebert, V. and Emely, G. (2020) Sawahlunto: Towards a Sustainable and Attractive Place to Live, Work and Recreate. Edited by J. Corten. Amersfoort: Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands.

•Ichsan, R. D., Rizkika, T. and Kamelina, E. (2023) Sawahlunto Municipality in Figures. BPS Kota S. Edited by J. Martiyus, I. A. Andri, and E. Kamelina. Sawahlunto: BPS Kota Sawahlunto.

•Kuswartojo, T. (2001) Sawahlunto 2020: Agenda Mewujudkan Kota Wisata Tambang yang Berbudaya. Bandung: Pemerintah Kota Sawahlunto.

•Martokusumo, W. (2016) ‘The Rise and Fall of a Former Mining Town Sawahlunto: Reflections on Authenticity and Architectural Conservation’, PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND Vol. 33, (July), pp. 418–428.

•Rahmi, L. (2017) ‘Analisis Proyeksi Pertumbuhan Penduduk Terhadap Kondisi Ketenagakerjaan Di Kota Sawahlunto Sumatera Barat’, Georafflesia, 2(1), pp. 95–106.

•Suprayoga, G. B. (2008) ‘Identitas Kota Sawahlunto Paska Kejayaan Pertambangan Batu Bara’, Jurnal Perencanaan Wilayah dan Kota, 19(2), pp. 1–21.

Comments (0)