Cities and movement go together. Cities are the result of the movement of people, goods and ideas as well as the movement of energy and water. Today, even digital data is important. Our major cities are full of movement; they deliver optimal conditions for movement and profit from it. Abolishing movement or separating it from the urban public space would be the biggest mistake for a city. Yet, creating a proper relation between urban space and movement is not easy. An important question for urban designers and city planners is how to create optimal conditions for attractive urban spaces and efficient movement.

A ‘classic’ question

The question about a good relationship between movement and the city is very old. In ancient times, the Greek philosopher Plato and the Roman philosopher and senator Seneca had opposing views. Writing about his ideas on the spatial structure of the city, Plato urged to make a strict distinction between the ‘Agora’ and the ‘Emporium’. The Agora was the square of public and political debate, it belonged to the citizens who lived there and should not be ‘infected’ by commercial or religious happenings. Foreigners were allowed to come to the ‘Emporium’, next to the harbour, where it was possible to sell and buy goods. While the Emporium was dominated by temptation, ruse, misleading beauty and deceit, the Agora should be protected as a place for rational arguments and content. On the other hand, Seneca regarded Ostia, the harbour of Rome, as the most important place of the city and asked for a more central position for the Ostia in the plan of Rome. He considered it important for Roman citizens to see the everyday arrivals and departures of ships and people from foreign countries. Seneca considered the openness for new cultures, habits and tastes a basic aspect of cosmopolitan citizenship.

City squares and car squares

This basic controversy between regarding movement as a danger versus movement as the source and the engine of urban life, has dominated the debate on urban design and urban planning for centuries all over the world. After the Middle Ages, during the first period of urban growth in Europe, many cities were built as fortified entities, surrounded by strong walls. These walls emphasised the separation between the safe interior of the city and the wild and dangerous exterior of the rural landscape dominated by gangs, warlords and thieves.

Many cities emphasised their safety and civilisation by the design of new squares, creating space for a civilized civic culture. Famous examples are the Piazza del Campo in Siena (Italy, 14th century) and the Dam Square in Amsterdam (The Netherlands, 17th century). In sharp contrast to these distinguished urban spaces were the so-called ‘car squares’, just outside the city walls near the gates. People who travelled to the city with their own cars full of vegetables or other goods, were forced to leave their cars outside the city wall and to transport their goods to the city marketplace in small cars or on foot. The car square became the space of arrival and departure of many foreigners: a parking place for their cars that was surrounded by bars, inns and brothels.

The difference between a regulated world in the medina and kashba and a more ‘wild world’ in the spaces around it can be found in many African cities. A famous example is the Plaza de Yamaa el Fna in Marrakech (Morocco), which was the site for the arrival and departure of camel-caravans through the desert. Though the camels have now been replaced by Landrovers and Jeeps, the square is still full of soothsayers, story-tellers, dentists, hairdressers, medical advisors and flute-players, all going about their work in the open air. Urbanity at its best.

The car square became a parking place for cars that was surrounded by bars, inns and brothels

Port cities

During the 19th century, the rise of the steamship goaded many coastal and river cities to extend their port areas in order to play a central role in the increasing global traffic and trade. Cultures, smells and tastes from all over the world could be experienced at these port cities. Some looked on this as an opportunity to deliver a public ‘balcony to the world’, where people could get to know the activities, goods and people from countries far away.

In Italy, the city of Genova built a large storehouse in front of the harbour, with a large public promenade on the roof. The citizens of Genova considered the rooftop promenade the most important public space of the city. A current echo of this concept can be found in Shanghai, where a new flood defense construction has been built on the famous waterfront area Bund, combined with shops and restaurants and with a public promenade on the roof. During summer nights, thousands of Chinese citizens walk on it as they gaze at the tourist sightseeing boats on the river and the commercial Pudong district across the river. Liverpool in England, a 19th century port city, tried to attract tourists, providing special sightseeing tours by a brand new metro system, which connected the city centre with the new port.

But some cities emphasised their fear about the influences of strange people and their cultures. Most of the European ‘Chinatowns’ were the result of the policy of city administrations to concentrate Chinese sailors in districts that were easy to control by the police. The largest Chinatown of the European continent of the 1920s and the 1930s was in Rotterdam. The city administration used the peninsula Katendrecht, between two harbour basins, as the exclusive area for the concentration of Chinese sailors. A special police station was built at the entrance of the peninsula, controlling all incoming and outgoing people. Local newsletters wrote about the Chinese sailors as ‘strange people with strange habits’ and any interaction with the civic community was to be avoided. However this attempt to avoid any ‘infection’ of the people of Rotterdam by the Chinese was not very successful: it didn’t take very long for the Dutch to discover the richness of the Chinese kitchen. A trip to Katendrecht and a visit to a Chinese restaurant was soon a nice change in the everyday life of the local citizens.

Boulevards and Avenues

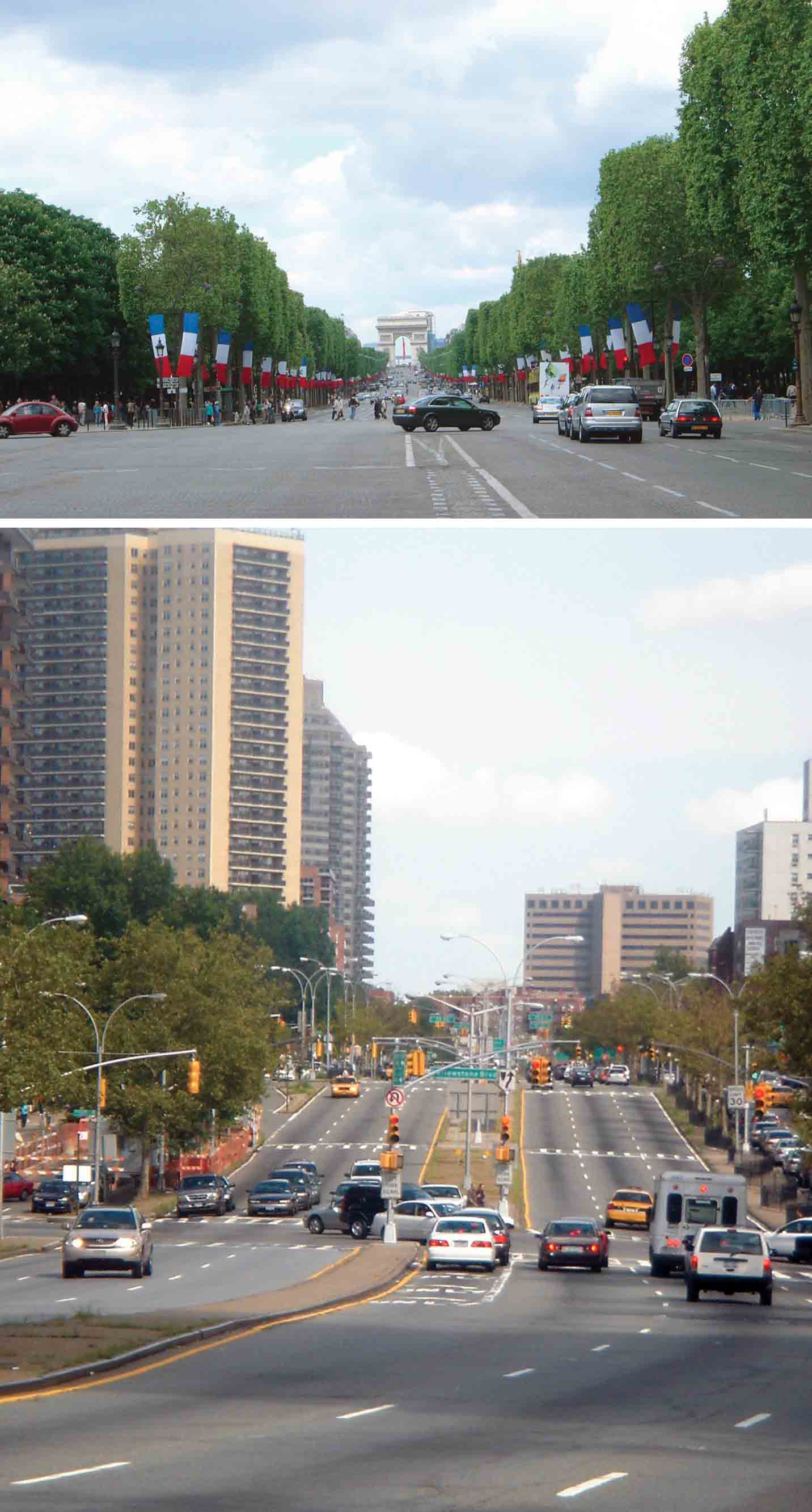

The rise of the industrial age did not only result in an increase of traffic by ships, but also by cars on land. Initially, in the 19th century, it was the rise of horse cars, dog cars, coaches and, not to forget, pedestrian traffic. To cope with this increasing traffic, city administrations started to provide their cities with broad and straight boulevards and avenues. Paris, Vienna, New York and Barcelona were leading benchmarks; their new networks of boulevards and avenues inspired many other city administrations to undertake comparable interventions. These boulevards and avenues provided space for a wide range of different kinds of traffic and came to be regarded as a moving melting pot of different people and different speeds. The German philosopher Walter Benjamin described Paris as the ‘Capital of the 19th Century’, with the boulevards as the ultimate expression of the modern time, providing a stage to beggars as well as to extremely rich idlers.

Most of the European ‘Chinatowns’ were the result of the concentration of Chinese sailors in districts which were easy to control by the police

The rise and fall of the modernist city

Opinions changed in the 20th century. Modernists like Le Corbusier and Giedion considered the 19th century boulevards awful and chaotic expressions of a lack of civilisation. According to their ideas, movement in the modern city had to be clean and separated from residential areas and from the core of the city. The rise of the automobile created the possibility to realise their dreams. The American city planner Robert Moses proved to be the champion of modern city planning by building a large network of expressways and parkways in the City and the State of New York. The construction of this road system led to the demolition of large parts of the city and to the isolation of city districts, separated from one another by expressways. Moses agreed with Le Corbusier that the 19th century city with the networks of streets and boulevards had to disappear, making place for a new type of city of skyscrapers and expressways. In his vision, people who were not able to buy a car were not real Americans, they didn’t earn to participate in the modern society and should be concentrated in isolated social housing districts.

It was Jane Jacobs who criticised this approach in her famous book, Death and Life of Great American Cities (1960). She argued that the interventions of Moses would lead to the death of the city, destroying everything which was a condition for vitality and diversity. Jacobs described her own neighbourhood (Greenwich Village) as a lively and vital neighbourhood, with an interesting mix of streets, squares and boulevards, providing space for all kinds of activities and contacts – in other words, providing space for urban life. Her book proved instrumental in bringing about a fundamental change of opinion in many cities of the world. The relationship between city and movement was under discussion again.

Bottom: Queens Boulevard, west of Yellowstone, New York

Cities and movement in the 21st century

Since the 1980s, many interesting experiments have been carried out in several cities. The city of Barcelona presented itself as an experimental laboratory after the death of dictator Franco. Many experiments were carried out to create a new type of open city, linking urban public space with movement. One of the most radical examples is the historic harbour front Moll de la Fusta, which was in a desperate position because of the presence of a 16-lane ring-road. The new generation of urban designers succeeded in transforming this area into a favourable combination of a half-covered highway track, an urban road for domestic traffic and a pedestrian boulevard alongside the harbour.

New experiments were applied not only in Europe but also in Brazil where fresh concepts for urban boulevards were constructed. New parkways in Rio de Janeiro connecting the city centre with the beach area of Copacabana provide not only a pleasant drive for those travelling by car, but also for cyclists and pedestrians. Every Sunday these highways are closed for cars and are used as public areas where people walk, jog, cycle, dance, organise barbecues or just sit and observe.

Modernists like Le Corbusier and Giedion considered the 19th century boulevards awful and chaotic

A new dimension

A new chapter in the relationship between city and movement concerns the mass migration by people from the rural areas of China, India and Africa to the cities, and also by people escaping the warzones in the Middle East and looking for safety and livability in European cities. These migration processes are not a temporary incident, but a start of a new development, which will increase in the future. Climate change with problems like desertification, water-shortage and a competition concerning energy sources will result in an increasing vulnerability of many parts of the world. The new mass migration processes pose a challenge to the capacity of cities to deal with this new movement. It means that the relation between cities and movement should be redefined. It is a new appeal to cities to be really ‘urban’.

All Photos: Wikimedia Creative Commons

Comments (0)