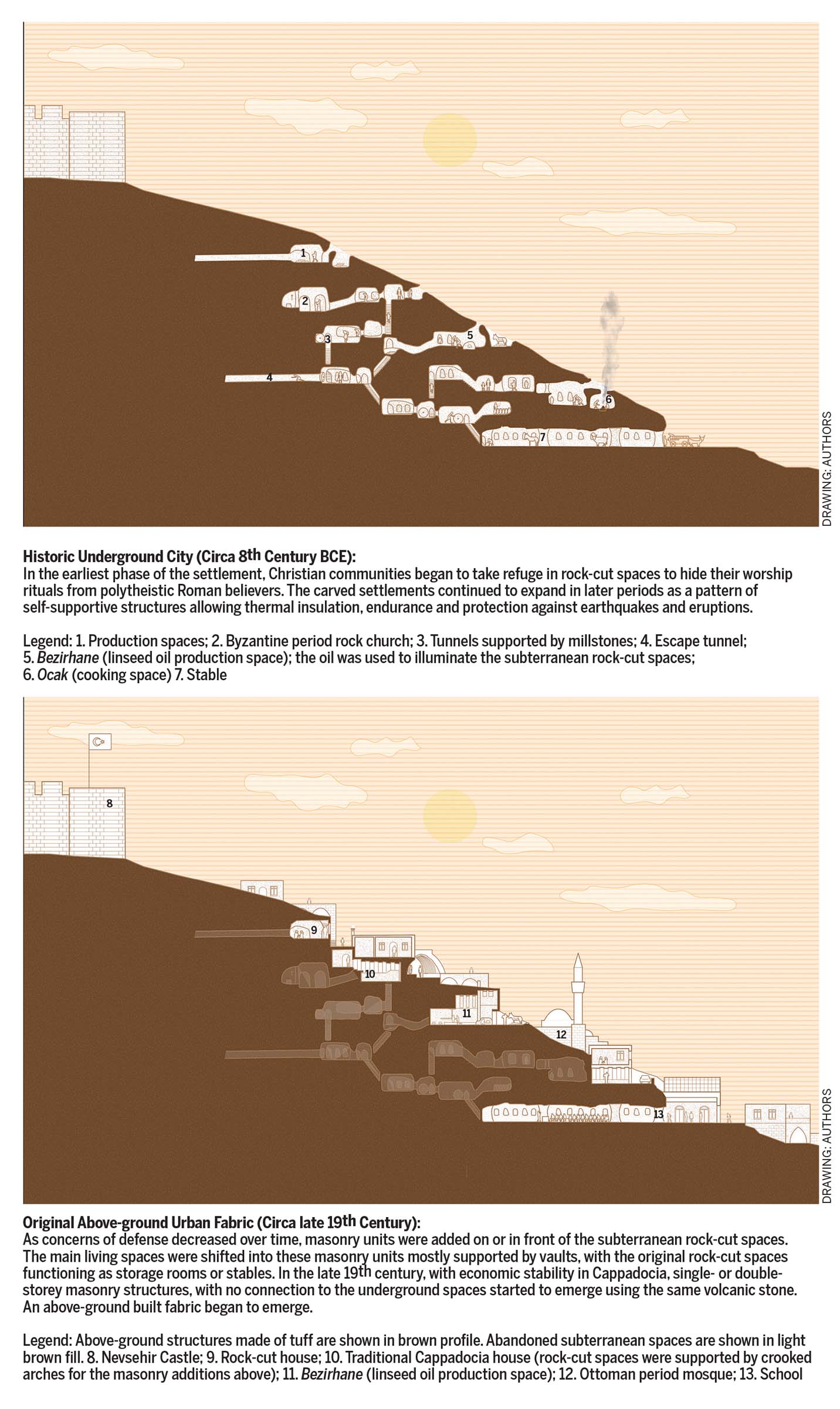

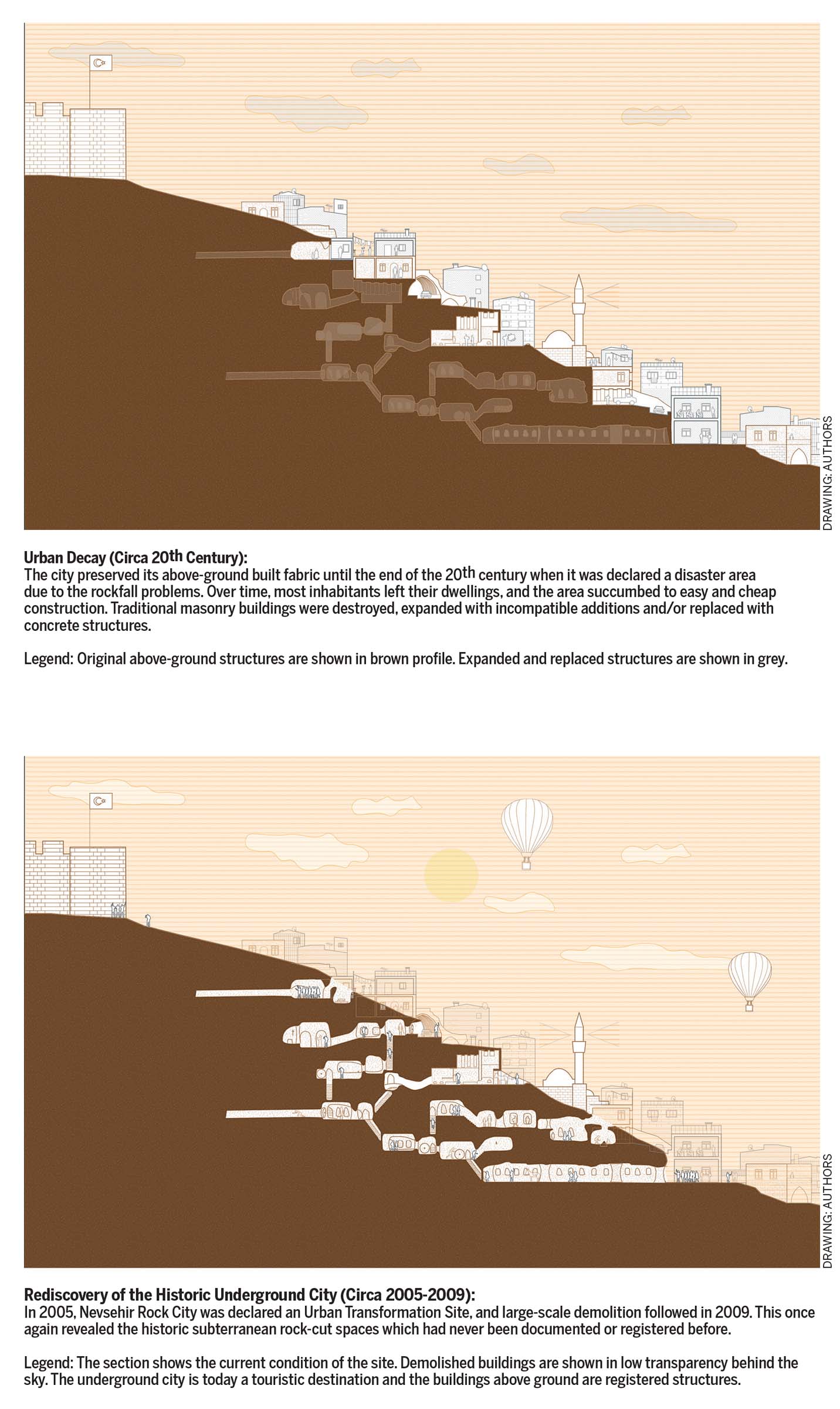

Cappadocia is a unique historic region in the Central Anatolia Plateau in Turkey. Its peculiar volcanic landscape of plateaus, valleys, canyons and other rock formations was created by the erosion of soft volcanic deposits in the surrounding peaks, more than 60 million years ago. The volcanic ash rock (tuff) is easy to excavate and sculpt, and hardens quickly upon contact with air. This has enabled a centuries-old lineage of multi-level horizontal and vertical rock-cut spaces within the tuff. Over time, the tuff has been carved by various civilisations to create human settlements, originally underground and, subsequently, above ground, using the tuff as a structural material. Most of these settlements have survived to this day.

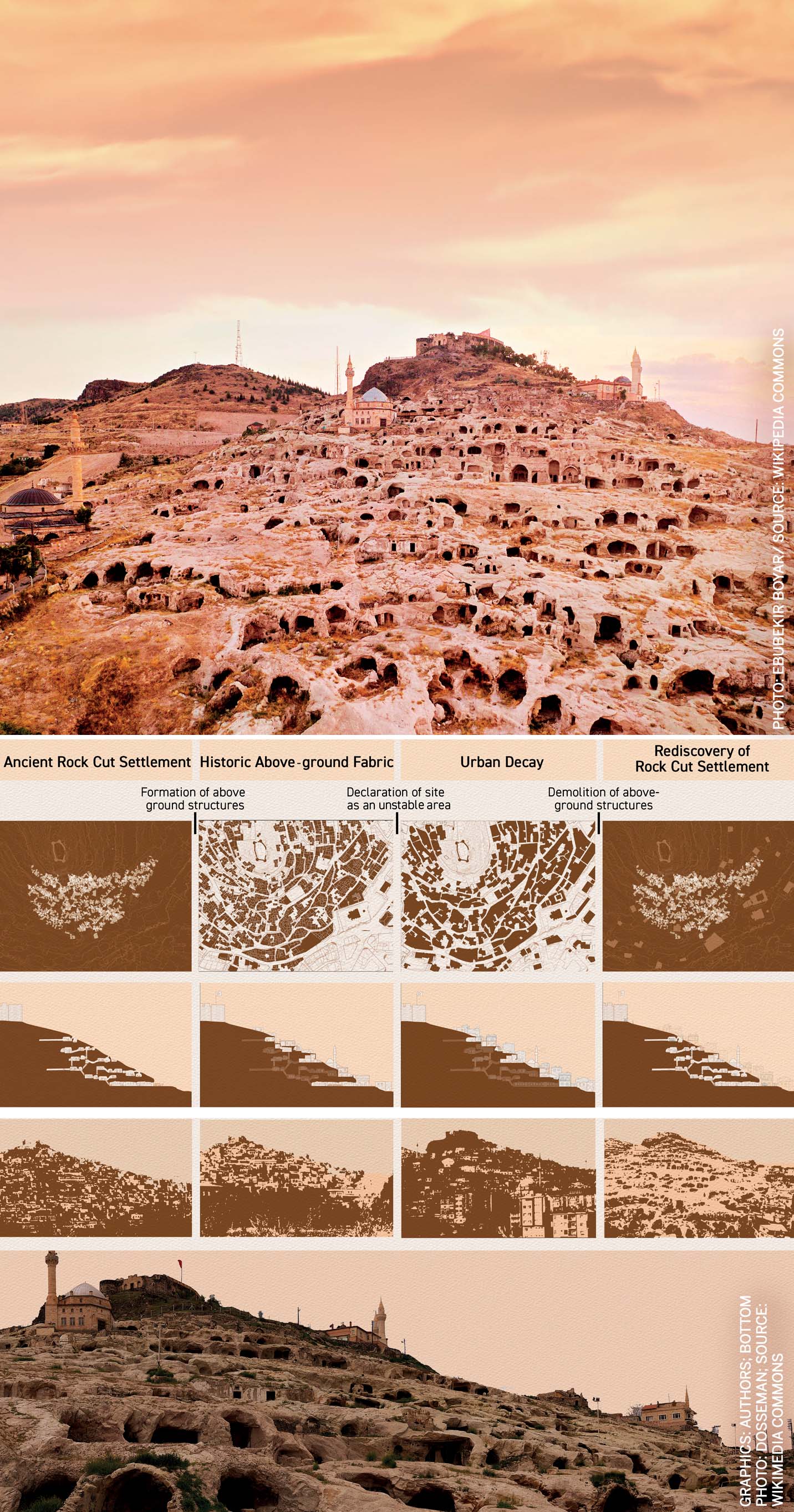

Nearly 1,000 rooms have been discovered in this volcanic rock settlement, creating a colossal interconnected subterranean labyrinth

Bottom: Evolution of Kayasehir over time

|

|

|

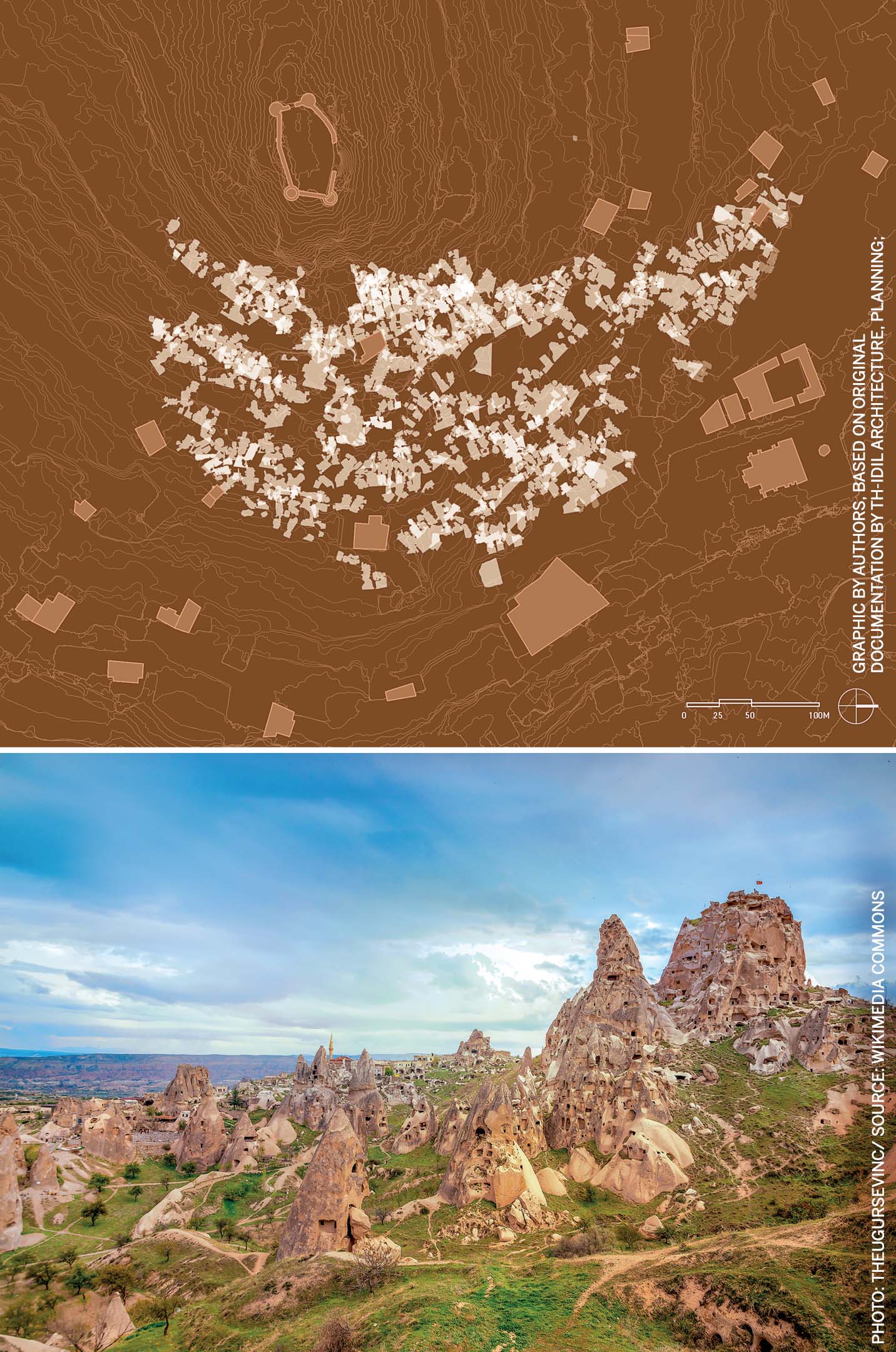

Bottom: Uchisar Castle is yet another rock-cut settlement in the Cappadocia region

The rock-cut settlement covers an area of approximately 437,400 square metres

Kayasehir (‘Rockcity’ in Turkish) located in the city of Nevsehir is one such rock-cut settlement with masonry buildings above. Its subterranean spaces had remained hidden and undocumented until the recent selective demolition of the above-ground structures. The settlement has a multi-faceted history: one can see a rock-cut monastery dating back to the 6th century, a Byzantine rock church from the early 13th century, spaces for trading activity created during the Ottoman period between the 14th and early 20th centuries, and stables that later functioned as schools. Some of the multi-level subterranean spaces are connected by tunnels supported by millstones that can be rolled on the ground to block the passage for security, or used as traps during enemy aggressions. Per the web resource http://www.nevkayasehir.com, 320 habitable spaces and nearly 1,000 rooms have been discovered in this volcanic rock settlement, creating a colossal interconnected subterranean labyrinth, covering an area of approximately 437,400 square metres.

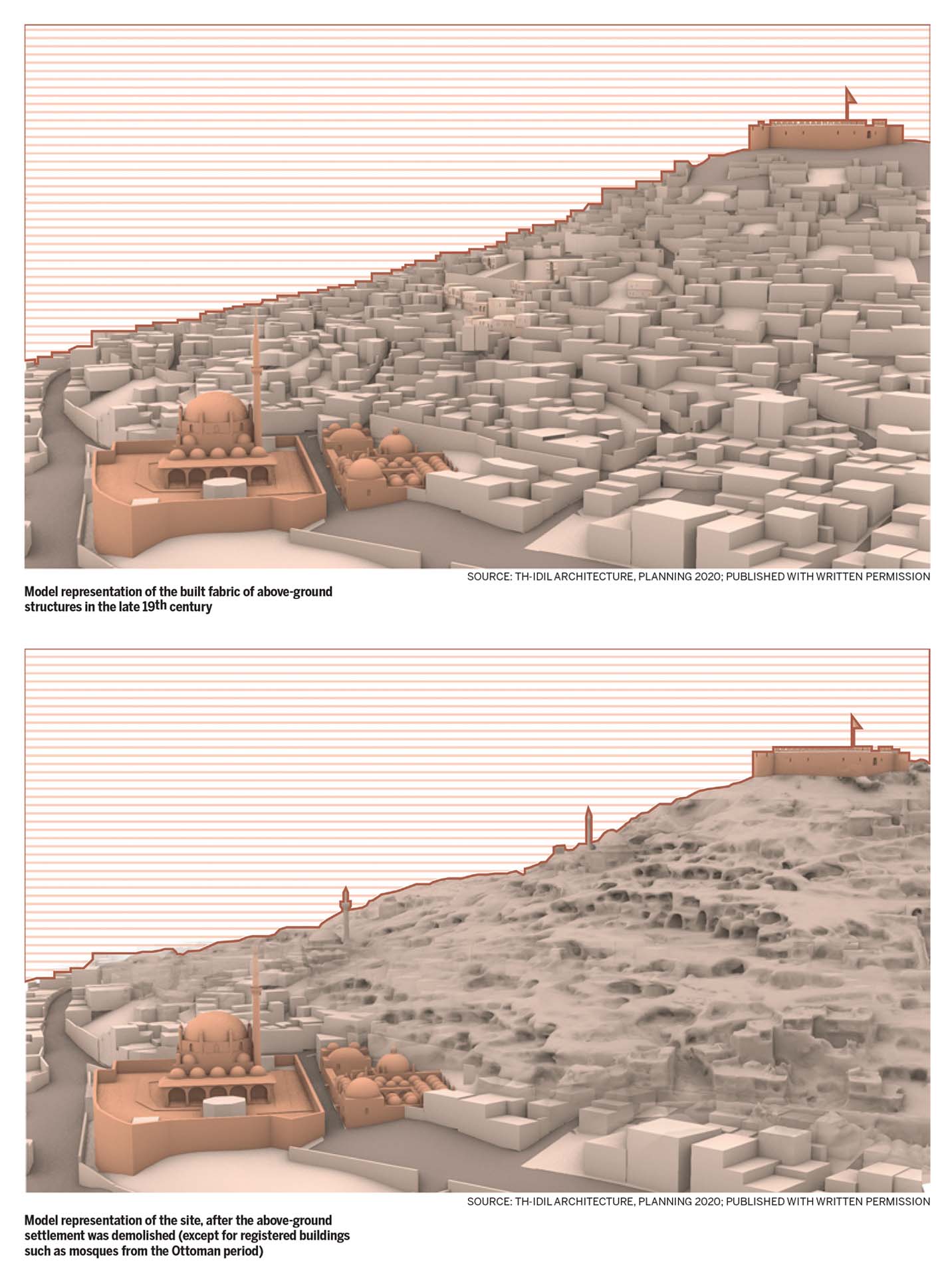

A graphic documentation of the evolutionary morphology of this extraordinary settlement follows.

The Nevsehir Rock City is not the only one of its kind, or largest rock-cut settlement in the Cappadocia region. The Derinkuyu underground city is the largest extending to a depth of approximately 85 metres (280 ft) and is estimated to have sheltered as many as 20,000 people together with their livestock and food stores. The Uçhisar Kalesi is another example, a 60-metre-high rock formation crisscrossed by numerous underground passageways and rooms. All these Rock Sites of Cappadocia were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985 under the natural and cultural heritage criteria.

We would like to thank TH-IDIL Architecture, Planning, Turkey, for permitting us to republish their model studies of Nevsehir Rock City.

Comments (0)