“Each tragedy has its silver lining. When cities are destroyed beyond recognition in conflicts, the need for rebuilding presents an opportunity for the community to redraw the physical landscape, to make it stronger and grander than it was before.” - Robert Frost, A Servant to Servants, (from his collection of poems North of Boston, 1915)

Heritage conservation and the renewal of historic cities are about the maintenance and the preservation of the built environment. The concept is different when it comes to rebuilding cities after a crisis. When a city is destroyed beyond recognition, the need to rebuild provides a fresh opportunity for the community to accept the change and redraw the physical landscape, to make it stronger than it was before. War is considered the most violent form of destruction, which in addition to human loss, commits devastating violence against the urban fabric of cities.

The city of Aleppo has suffered damage over history for many reasons. It was invaded several times and destroyed by enemies as well as by earthquakes. The latest destruction of Aleppo during the Syrian War is one of the most devastating in modern history and the 21st century.

Aleppo could be considered one of the oldest human settlements and one of the most picturesque cities in the Middle East. The most important city in modern north Syria and the second largest city in the country after the capital Damascus. Aleppo was a Syrian mosaic; it was the home of diverse ethnicities and faith communities. Arab and Turkish, Kurdish and Armenian, Christian, Muslim and Jewish, all lived peacefully on this land for ages.

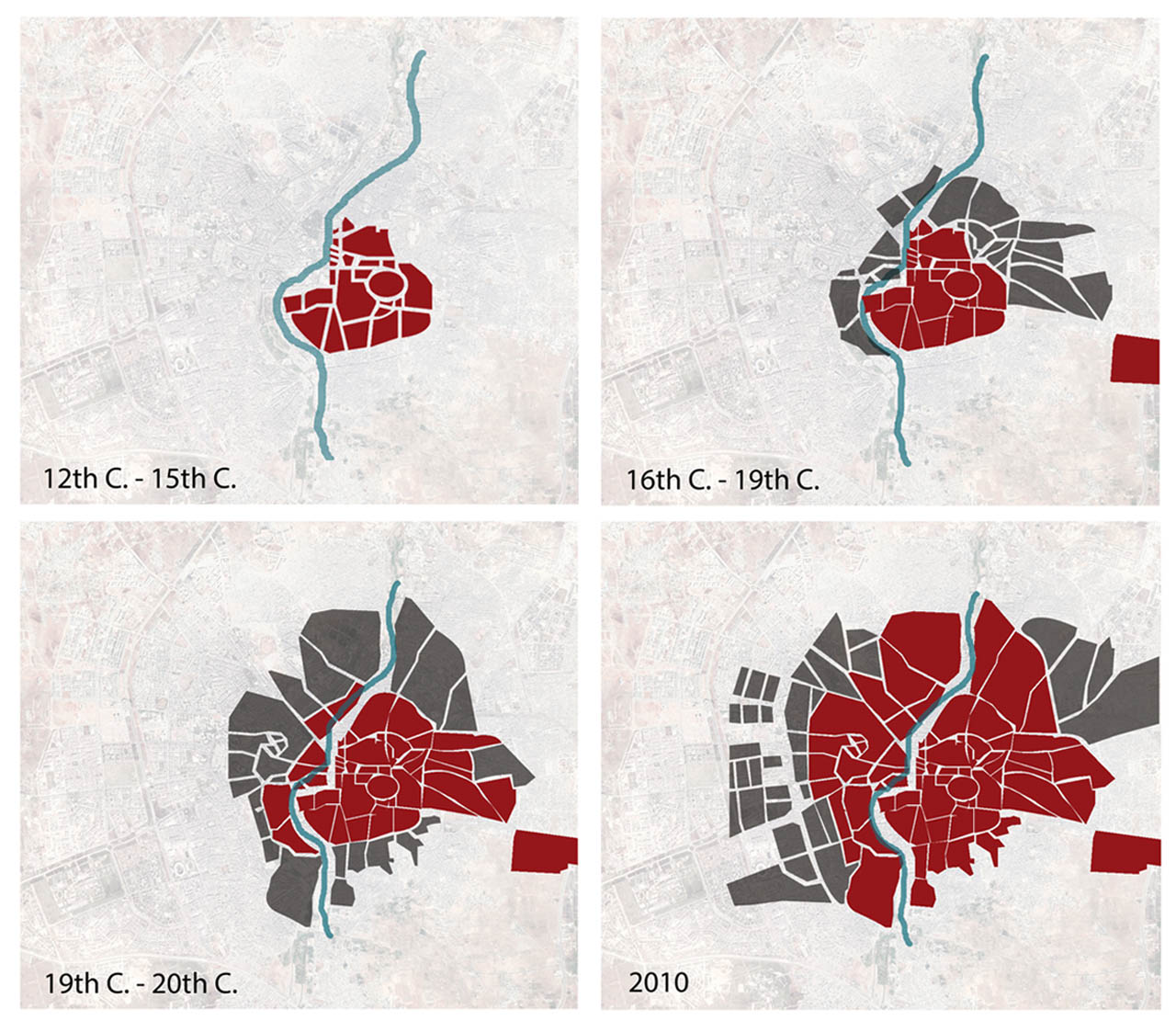

Aleppo is considered one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. It was, for a long time, the cultural and commercial centre in north Syria. The commercial role of Aleppo started as early as the 2nd millennium BCE. It was an important trade centre and a destination for trade caravans on the famous silk route, which connected the east and the west. It reached its peak between the 16th and the 18th centuries CE. One of the great religious centres of ancient times, the sanctuary of the storm god Adda was discovered in Aleppo at the location of the citadel. The traditional fabric extended horizontally around the citadel and outside the defensive walls to cover an area of 465 hectares. It includes souqs (traditional markets), mosques and madrasas of the old city.

Aleppo is considered one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world

The old city still maintains the Roman street layout from the Hellenistic Period and some of the buildings from the 6th century, like the Saint Helena Byzantine Cathedral, which was converted to an Islamic school (Al- Halawiyah Madrasa). It also maintains buildings and remains from the Ayyubid and Mamluk mosques and schools and many Ottoman period structures.

Similar to conflicts, heritage can also be destroyed in peace times. During the 20th century, as a result of the urban modernisation plans in the city, fundamental changes affected parts of the traditional fabric of the old city. The plans, which were proposed to connect the old city to the modern expansion and provide automobile access to the old city, were implemented during the French mandate period from 1920 to 1946. The concept, which was similar to Haussman’s modernisation of Paris between 1853 and 1870, affected the old city and caused a systematic destruction in the old neighbourhood. Despite the changes in the historic fabric, the city still maintains its traditional urban character as an Islamic urban area with a rich heritage and long history.2 The Ancient City of Aleppo was added to the World Heritage list of UNESCO in 1986. After becoming a World Heritage Site in 1996, Aleppo received national and international attention and many initiatives and financial support under the umbrella of the Rehabilitation Project of the Old City of Aleppo, which produced impressive results.

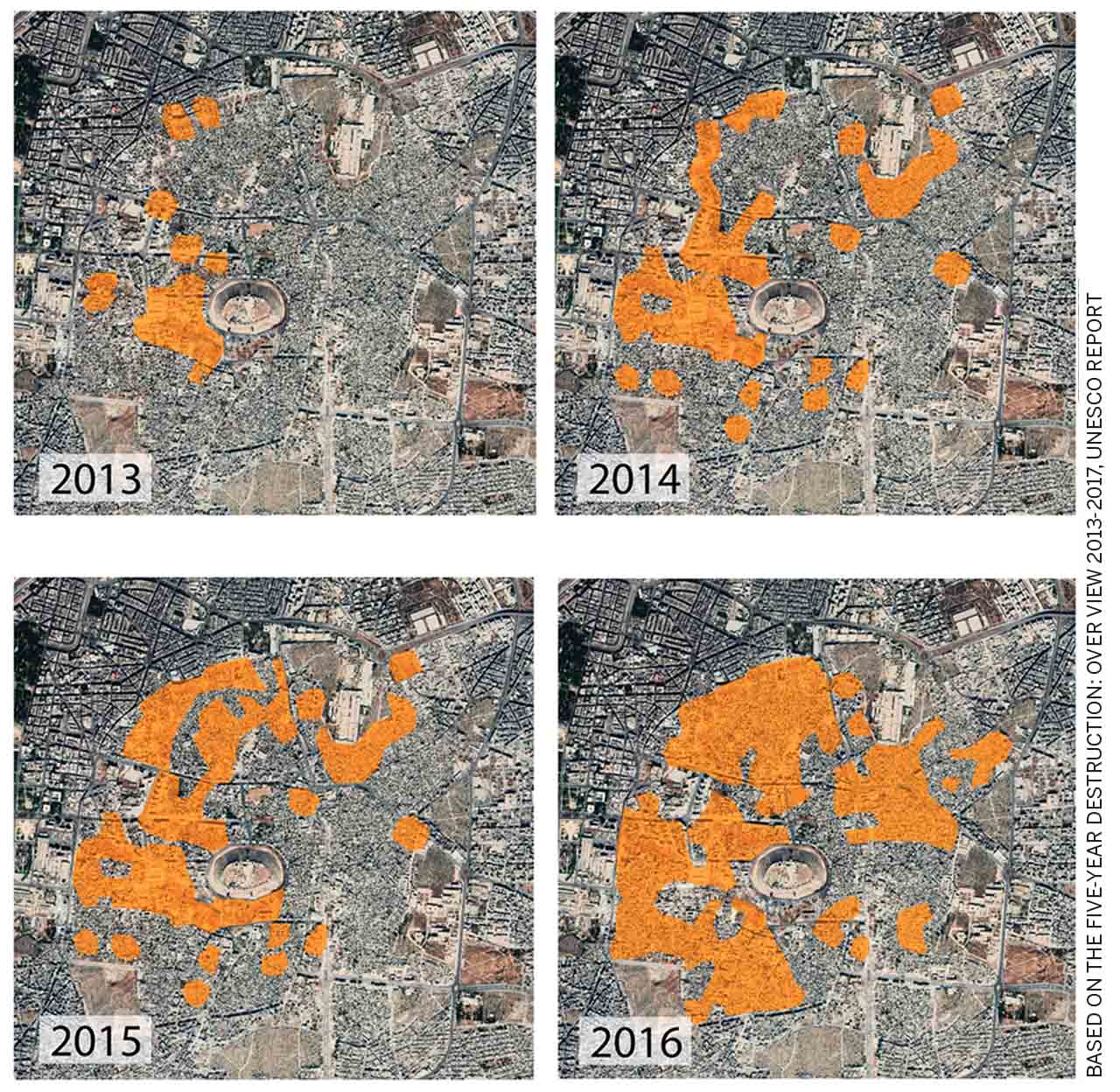

In July 2012, a date that marked the second year of conflict in Syria, Aleppo became part of the war, with the result that it very quickly became the most disastrously affected city. Aleppo had the largest share of damage to its built environment, loss of human lives and mass migration and relocation. During the conflict, it was almost impossible to access many areas in the old city of Aleppo; only militant forces from both sides were able to record the damage and publish it in the media.

In December 2014, while the conflict continued, the DGAM (Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums) feared the loss of the archives of the city and started digitising the records and plans of castles, museums, archaeological sites and mosques in the province of Aleppo in general including the citadel of Aleppo and the monuments of the ancient city as part of the campaign. They also worked on the documentation of the neighbourhoods that are located outside the boundaries of the old city of Aleppo that contain buildings and structures from the French mandatory period.

The DGAM worked in Aleppo in cooperation with local communities and stakeholders including the Municipality of Aleppo (represented by the Directorate of the Old City), the Directorate of the Old City of Aleppo, the University, the GCES and international organisations like UNESCO, ICOM, ICOMOS, ICCROM, the Arab Regional Center for World Heritage (ARC-WH) in Bahrain and the World Monument Fund (WMF) in exchanging visions and data, raising awareness and building capacity in the city. The local professionals of Aleppo showed an incredible dedication in the documentation work, undertaking mitigation actions during the conflict, as well as emergency measures for the recovery phase by participating in the working meetings with the Aleppo City Council, the DGAM and NGOs to identify adequate proposals and coordinate action.

The government, the people of Aleppo and the international organisations were all ready to offer knowledge, experience, time and efforts to rebuild old Aleppo

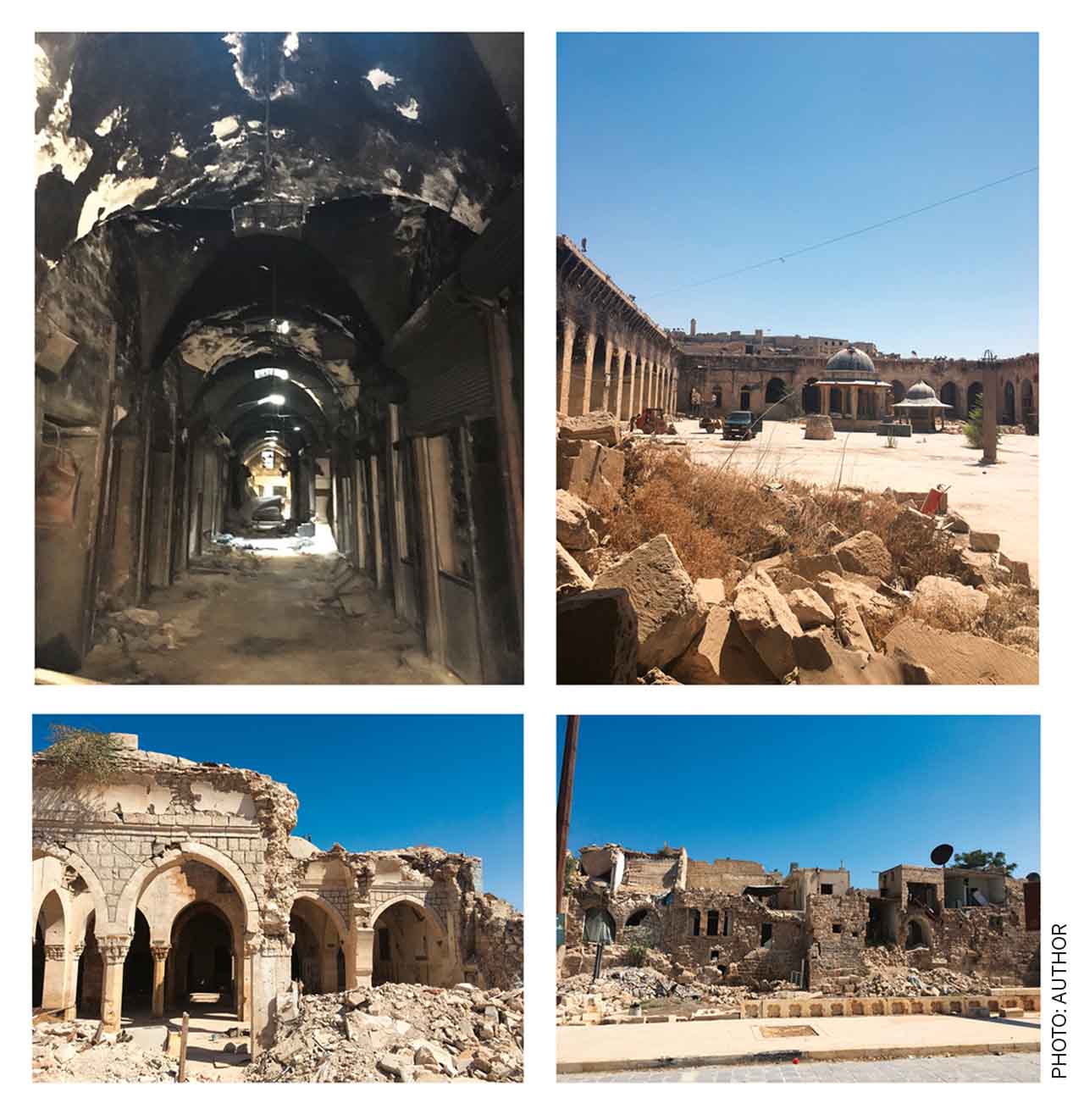

In 2016, the old neighbourhoods were accessible after the efforts of the Directorate of the old city to clear the rubble and assess the damage. According to the General Company for Engineering Studies in Syria (GCES) assessment report published in 2017, 20.5% of the city’s fabric is severely damaged and needs rebuilding, 9.8% of it is destroyed, 58.8% of the city’s fabric is slightly damaged but can be rehabilitated and 20.7% of the city’s fabric is intact. The damage affected many important city historic monuments including the Great Omayyad Mosque and its 1000-year-old Omayyad minaret, the area around the citadel of Aleppo in the heart of the old city, the traditional linear market, which is considered one of the longest covered traditional markets in the world and many others. Another damage assessment was done by UNESCO, which used five different levels to assess the physical situation of the historic properties inside the Old City of Aleppo and documented a detailed list of damage at 518 cadastral-plotted buildings.

The reconstruction in the city of Aleppo started in 2016 when the old city was free of conflict. The government, the people of Aleppo and the international organisations were all ready to offer knowledge, experience, time and efforts to rebuild old Aleppo. UNESCO considered providing consultation, staff training and monitoring of the reconstruction work to make sure that the reconstruction and restoration are being carried out based on the approved restoration guidelines.

The traditional fabric of the old city of Aleppo was based on the idea of providing privacy to the residents in their own houses. The city has always been a safe and convenient place for the residents that combines residential buildings, trade and business, religious and community gathering destinations. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture provided an intervention plan that covered three main areas in the old city; these areas were chosen because they include a variety of uses and priorities were defined based on the historic importance and the extent of damage. The local community is also making an important contribution in the post-war recovery phase. Home and shop owners as well as wealthy residents funded the rebuilding and the restoration of many buildings and historic monuments, especially the religious buildings that were a priority in this process. The restoration of the Maronite Eparchy (St. Elijah), which was funded by the ACN (Aid to the Church in Need), an international body, and the restoration of the Great Umayyad Mosque as well as the reconstruction of the completely destroyed minaret, which is also funded by another international body, are both examples of prioritising the city landmarks in the rebuilding process. Many residential neighbourhoods were devastated, some of them were flattened to the ground like Al Aqaba, Al Farafra and the entrance of Al Jdaydeh in the area that connects Al Khandak street with Al Hatab square.

Even though these areas of the old city are in urgent need of reconstruction, the focus is on the reconstruction of the religious buildings and the traditional markets.

Rebuilding the residential neighbourhoods is necessary for the return of the inhabitants of the old city. It is as important as rebuilding the identity of the people by reconstructing their dearest places and bringing back their most meaningful symbols.

The residents of the old city can help in deciding where to start and what to rebuild; this may bring a bottom-up decision-making strategy to the table, instead of the top-down strategy that is already being considered since the beginning of the post-war rebuilding process.

Reconstruction of cities post-war is not a new concept; it has always been more than rebuilding the destroyed monuments and making the cities look as they did before the conflict. This makes it different from the urban renewal of modern cities in peaceful times.

The renewal of an ancient city like Aleppo, with a rich tangible and intangible heritage, should take an approach that supports the rebuilding of the community together with the built environment. This includes rebuilding the cultural identity of the people. Many aspects of Aleppo’s intangible heritage were affected during the conflict and the displacement of the residents, which makes it important to target people, educate them and raise their awareness of the value of their heritage and make them part of the decision making. People of the city can heal the heritage and heritage can heal them in a reciprocal relationship to create a healthy post-conflict society.

Conflicts are one of the reasons for the change in the urban and social structure in the city. It should be a reason to generate a new way of thinking and new strategies. The consequences of conflict and change are part of the lifecycle of the city and the history of any heritage site. When a transformation occurs and the change happens in the urban built environment and the social structure of the city, it can’t simply return to what it used to look like earlier. The rebuilding should bring opportunities to improve the quality of social life and serve in the reconstruction of the wounded communities. Most of the challenges that may hamper the rebuilding process are related in many ways to political decisions in the country, international intervention and deciding who is going to be allowed to participate in this phase.

Yet, there is a chance to find a balance in rebuilding Aleppo, where actors from the local community can participate in this practice. Those actors could be a group of representatives from the local community who care about the old city; many of them have the experience. This group includes historians, preservationists, architectural historians, craftsmen, merchants and shop owners who can enrich the decision-making process. Many of the commercial and touristic property owners took charge of restoring their properties to bring back life to the old city. These included antique shops, craft shops, restaurants and hotel owners. The reconstruction process could be the key to solve the problems in the old city, which were a result of earlier interventions, like the multi-storey buildings in many neighbourhoods. The rebuilding should bring opportunities to improve the quality of social life and serve in the reconstruction of the wounded communities.

This paper is an attempt to encourage the collection of all the efforts and guidelines to help serve the recovery of the historic part of Aleppo and make sure that Aleppo can become a good example for the recovery of cities from disasters in the future. A major lesson, where a World Heritage Site like the old city of Aleppo has been devastated as a result of the conflict in a world that widely understands the importance of cultural heritage for humanity, is that there must be more efforts to protect cultural heritage from destruction during conflicts. The international world should come together to protect its heritage.

References:

1. Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. “Ancient City of Aleppo.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed September 4, 2020 https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/21.

2. Perini, Silvia. “Towards a Protection of the Syrian Cultural Heritage: A Summary of the International Responses Volume II.” www.heritageforpeace.org, October 2014. http://www.heritageforpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Towards-a-protection-of-the-Syrian-cultural-heritage_Oct-2014.pdf.

Comments (0)