The word ‘smart’ carries many meanings. It can describe intelligence, how well you dress or even a stinging pain. For urban planners, however, ‘smart’ is now and forevermore associated with Information and Communications Technology (ICT).

Smart Cities deploy ICT into municipal infrastructure and institutional processes to meter, monitor and automate in ways that save money, increase efficiency and improve quality of service. It may be a network of cameras and environmental sensors that feed into an operations centre for day-to-day traffic management or emergency response. It may be GPS units in every city vehicle to improve routing, provide location data and making sure that municipal workers are doing their jobs. It may be smart grid or water metering systems that detect problems early and prevent costly crises from erupting. As Big Data technologies proliferate, it is becoming mostly about sophisticated analytics that produce useful forecasts from the new flood of data about the city.

The Internet of Cities

Smart Cities is really just another application of the Internet of Things, a term coined by MIT’s Kevin Ashton in 1999. That vision extends far beyond city streets or water mains to pills you can swallow containing sensors that report on what’s happening inside your digestive tract and disposable sensors in milk cartons that detect whether the temperature has remained in the right range. In the broadband economy, the network captures the value of billions of bits of useful data flowing through it.

Leading innovators in urban and rural planning are already taking these emerging technologies into account. But the leaders need more followers. Most vitally, the planning discussion needs to expand in scope.

Broadband and inexpensive IT will not just ‘capture value’, but redefine how communities operate in physical, social and cultural terms. Interactivity of people, things and places is transformative.

If broadband becomes as important to the local economy and culture as the street or sidewalk, how will it change the places we live and work? What priority should be given, for planning purposes, to the physical aspects of the network: fibre optic or copper cables, wireless routers on towers or rooftops, repeaters within structures?

But there is another level above and beyond the physical issues of wiring, fibre cabling, power provision and regulating antenna placement. That is the level of technology’s impact on people and the impact of user demand on technology. Both are already changing how people use space, demand space and relate to space and the changes will only become more radical with time.

The Amazing Shrinking Office

In 2010, real estate companies in North America told their clients that the average office employee needed 225 square feet (21 m2) of space. It proved to be a short-lived standard. According to real estate data provider CoreNet Global, by 2012, the North American average was down to 176 square feet (16 m2) and by 2017, it had shrunk to 151 square feet (14 m2). (1)

What is causing this? Individual offices gave way to open plans and a growing trend toward communal space for employees who are not expected to spend most of their time in the office. They are expected to be visiting customers or suppliers. They are working from home. They are using the mobile tools of the information age – laptops, tablets and smartphones – to cut the physical tether to the office while remaining connected, accessible and accountable to their companies. A February 2017 Gallup poll in the United States revealed that, from 2012 to 2016, the percentage of Americans working remotely four to five days per week grew from 24 percent to 31 percent. In 2016, 43 percent of employed Americans spent at least some time working remotely. (2)

This is only one small trend that is reshaping demand for office space in the central business district, as well as commuting patterns, sidewalk traffic and much else. In a March 2013 Webinar, Norman Miller of the Center for Real Estate at the University of San Diego, examined what would happen if US tenants used 20% less office space. He estimated that the change in demand would create US$ 250 billion in excess office capacity in a market worth US$ 1.25 trillion.(3)

The Amazon Effect

Offices are not the only commercial space under assault. Traffic in shopping centres in Europe’s biggest markets is in steady decline. In the US, Fung Global Retail & Technology expected nearly 10,000 stores to close in 2017, 50% more than at the peak of the financial crisis in 2008. In their place are rising warehouses that provide the logistics for fast delivery by Amazon and other online retailers. Citi estimates that 214 million square metres of new warehousing will be needed worldwide over the next 20 years. They will be located, not in city centres, but in the nearby suburbs.

Between 2007 and 2017, the number of retail jobs in America shrank by 140,000 while those in e-commerce and warehousing rose by 400,000, according to Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute.(4)

So, ‘smart’ is transforming the city in profound ways. The great question for city leaders and the urban planners who guide them is how the city should adapt to take advantage of the opportunities created by ICT, as well as to prepare its infrastructure, businesses and citizens to prosper in an age where the continuing broadband revolution will increasingly dictate success and failure. The following are three examples from the Intelligent Community network that our organisation studies.(5)

Putting the City in the Palm of Your Hand

The city of Columbus, capital of the US state of Ohio, has won numerous awards for a smart city mobile app called MyColumbus. At first glance, it is just another app. But it is something much more important: an equaliser of access to civic information and services in a community that, despite its economic success, still suffers from big disparities in income, education and health.

The MyColumbus app started out as a student project at Ohio State University. Students worked with the IT department of the city to identify publicly-accessible databases that could provide the most up-to-date information on city services, location of facilities and schedules of public events. They then built an app to access the data and turn it into easy-to-understand information.

The city’s IT department was so impressed with the result that, with the students’ permission, it hired a software company to expand the app and put a professional gloss on it. The resulting MyColumbus provides MyNeighborhood (location-based mapping and information about community resources, refuse collection and health inspections), GetActive (links to events, bike and trail guides and healthy lifestyle tips), GreenSpot (with information on sustainability) and 311 (where residents can log service and information requests). Service requests submitted via MyColumbus are resolved 3.3 times faster, on average, than telephone requests. Why? Because users can submit photos and GPS coordinates with their service requests, which helps maintenance workers show up with the right tools and materials to get the job done.

MyColumbus is effective because of the rich data that Columbus’s IT department makes available to it.

The city’s geographical information system (GIS) has hundreds of layers and supports applications including One-Stop-Shop Zoning, Utility Dashboard, Capital Improvements Planning, Fire Hydrants Inspection/Maintenance and that all-important function in snowy southern Ohio, Snow Removal. The data derived from databases, sensors and GPS flows through to operations managers, planners, businesses and citizens in a never-ending stream.

CREDIT: CITY OF COLUMBUS

Smarter Transit

The city of Rio de Janeiro has had a hard fall from the glory of the Olympic Games to today’s headlines about the massive corruption and waste that has tainted Brazil’s achievements of the past decade. One of those achievements, however, has an impact that will long outlast the scandals of today. Using the World Cup and Olympic Games as a lever to pry open financing, Rio began building a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system to connect its far-flung suburbs to the city centre. The city is geographically vast, divided by steep mountains and prone to flooding from heavy tropical rains. It is served by 42 private bus companies, but a typical commute from the suburbs into the centre could take 2 to 3 hours one way, at a cost that was significant to low-income workers.

The BRT changed all that. BRTs combine the best feature of a train – pre-ticketing, operation on dedicated roads that bypass traffic and platforms at boarding level – with the low cost of buses. The BRT system runs a 400-bus network serving 1.5 million riders at 140 stations. All buses are equipped with GPS that feeds a GPRS system transmitting data every 20 seconds including video from the inside of buses. They monitor every bus on every route, both express and local, to maintain proper schedules.

The combination of good physical infrastructure and data-driven central monitoring and control has reduced commute time from hours to 30-40 minutes. The impact on low-to-middle class workers is large, opening up more economic opportunity for people who cannot afford to live in the centre, but who badly need the income that tourism provides.

From Windmills to High Tech

Some of the most impressive adaptations to the opportunities and risks of the digital economy come from places that have worked longest on the problem. On the edge of Paris, just across the Seine, is the small city of Issy-les-Moulineaux, which translates into English as Issy of the Windmills. It grew up as the factory zone of the Paris metro area and, following the disruptions of the Second World War, resumed its role as the industrial engine of the region, but then watched its economy erode in the de-industrialisation of the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1980, the people of Issy elected Andre Santini as their Mayor, and he continues to serve as Mayor today. Over 35 years, his administration provided leadership that was by turns visionary, daring and enormously persistent.

First came the vision. With its proximity to the French capital and a major army base, Issy was already home to a small cluster of IT, telecommunications and R&D organisations. Mayor Santini came to believe that they represented the city’s future and made it his top priority to create a business environment that would attract many more.

As the ’80s gave way to the ’90s, the Mayor’s government made a series of investments that signaled its technological priorities. Issy became the first French city to install outdoor electronic information displays and the first to deploy a cable TV network. In 1993, schools introduced a smart card allowing pupils to pay for lunch electronically. The following year, the City Council rebuilt its meeting room for multimedia and began broadcasting Council meetings over the cable system.

In 1994, the Mayor also challenged city departments to create a comprehensive Information Plan based on the study of the evolution of the Internet in the United States. The Internet was then in its infancy: 1994 was the year when Netscape, creator of the first commercial Web browser, was founded in California. Under the plan, completed in 1996, a Steering Committee representing municipal departments and elected officials was created to oversee investment in projects and maintain focus on objectives.

Issy’s first version of an e-government portal was already online in 1996. By 1997, the Council added interactivity to its cable and Internet broadcast of meetings, inviting citizens to ask questions by telephone or email and get an immediate response. Public participation began to climb.

Right: Issy Business District

All this development took place before 1999, when France Telecom lost its monopoly. On the same day that the monopoly ended, Issy became the first city in France to offer businesses a choice of carriers because well before the deadline, Mayor Santini’s team launched negotiations with alternative carriers, which agreed to enter public-private partnerships with Issy to deploy networks. Over the next decade, as it continued to welcome competitors, Issy gained a total of six alternative broadband networks, passing 100% of businesses, government agencies, institutions and households. Issy also operates a network of hundreds of WiFi access points, with speeds up to 20 Mbps, around the city.

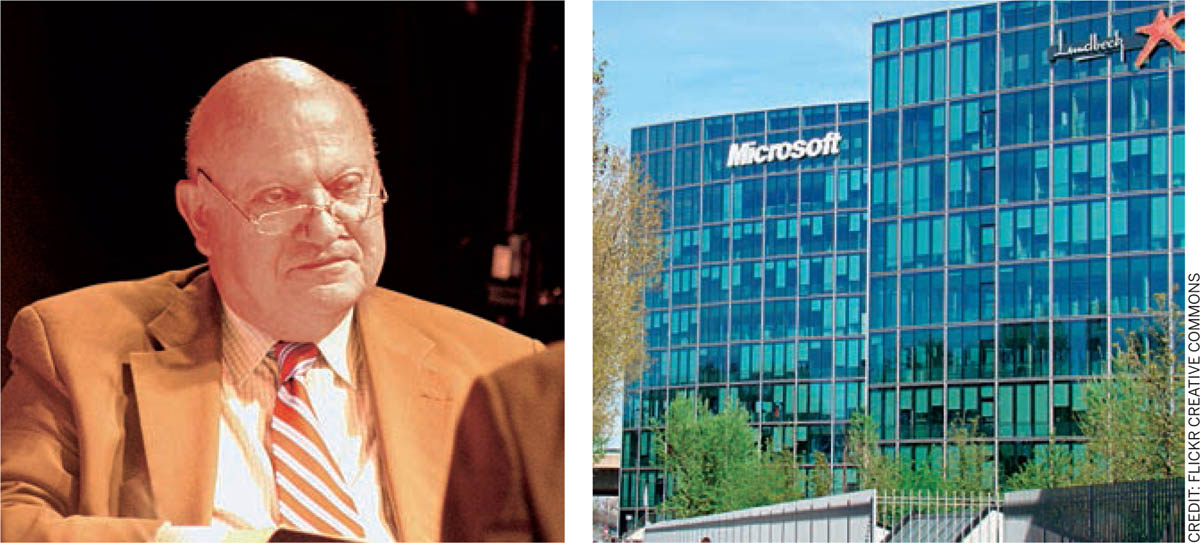

As a result of this rich array of offerings, nine out of ten Issy citizens are daily users of the Internet and 98% told a pollster that it has fundamentally changed their lives. More profoundly, the tech-based rebirth of Issy created an environment that attracted high technology employers. The city has more jobs than residents and 75% of its employers are in information and communications technology, ranging from Microsoft and Cisco to Sogetel and Amadeus.

Smart City technologies have great promise, but the vision needed to realise it is often lacking. Planners and local government leaders focus on saving money, increasing efficiency and introducing new services. These are all worthy goals. Of far greater worth, however, is the transformation of life, work, employment and ultimately business attraction and growth for the better. Aiming for the stars does not guarantee a handful of stardust, but it does guard against satisfaction with the safest result.

1 “What is the Average Square Footage of Office Space Per Person?” by Denis Mehigan, March 4, 2016, The Meghigan Company (mehiganco.com/wordpress/?;=684)

2 “Out of the Office: More People are Working Remotely, Survey Finds,” by Niraj Chokshi, The New York Times, February 15, 2017.

3 “Changing Office Trends Hold Major Implications for Future Office Demand,” by Mark Heschmeyer, CoStar.com, March 13, 2013.

4 “E-Commerce Takes Off,” The Economist, October 26, 2017.

5 “What is an Intelligent Community?” Intelligent Community Forum (http://www.intelligentcommunity.org/what_is_an_intelligent_community)

Comments (0)