From the Mandarin Route to colonial boulevards and canals to Soviet-style networks to contemporary grids for city extensions and industrial zones, there has been a conscious relation of movement, landscape and urbanism. Construction of infrastructure has always been strongly motivated by development expectations. With that comes an alignment of infrastructure with the most innovative and performant technical means available. Simultaneously, there has also been a constant appropriation of infrastructural spaces for a variety of unintended uses. Vietnamese sidewalks are proverbial universes of activities.

As the mobility revolution beckons, Vietnam has the opportunity to leapfrog development and largely skip the petrol-age: it can thrive with electric bikes and motorbikes, reinvigoration of its water transport network, various forms of public transportation and the sharing economy. At the same time, as one of the most severely affected countries by climate change, new street profiles can fundamentally redefine nature and culture relationships. As such, the assignment for new infrastructures is always multiple, generating a world of possible uses and meanings, while accommodating new means of transportation. In the coming post-petrol age, this creation of civics by technics necessarily has to incorporate much more sensitive relations with nature.

|  |

Legacy of imperial infrastructure

Humankind transforms nature in order to inhabit it. The process is never smooth, but invariably one of contestation. Transformations often emerge in the wake of violent upheavals, imbalances and contradictions. Infrastructures of all types are cultural-technical systems that disclose landscapes for development whether rural or urban, irrigation/water management networks, energy systems or transport arteries. They are inherently tied to their geographies and locational assets whether strengthening or defying existing landscape logics. In many instances, infrastructure innovation evolved from human necessity: the draining of wetlands for agriculture, waterways, roads and railroads for movement of goods and people, reservoirs for drinking water and irrigation.

Vietnam stretches 3,200 kms along the East Sea and the Gulf of Thailand covering 331,100 sq kms. It is a country of rugged topography; the land area is mostly mountainous rain forest, apart from river deltas in the north and south and a coastal plain. A majority of the ethnic Vietnamese (87% of the population) lives in only one-fifth of the country’s land area. Vietnam’s farmland supports more than 900 people per square kilometre, making it more than three times as densely populated as nearby China or Thailand. The remainder of the population consists of 53 ethnic minority groups, primarily living in the highlands of the centre and in the mountains of the far north. Its population of 97 million makes it one of the world’s most populous nations.

Most of Vietnam’s people, rice production, industrial output, political power and cultural activity are concentrated in two relatively small areas centered on the Hanoi-Haiphong axis in the northern Red River Delta and Ho Chi Minh-Bien Hoa-Vung Tau axis in the southern Mekong River Delta. The two plains are connected by a narrow strip of mountains, foothills and plain, which in some places is only 50 kms wide.

The strip of mountains is articulated by a series of relatively small rivers, amongst which the Perfume River generated the Tam Giang-Cau Hai lagoon system in the Thua Thien Province of central Vietnam. Each of these river basins forms a discrete but interconnected geographical unit. The long geography not only creates different weather patterns but, as a chain of river basins, also poses challenges for communication, infrastructure and political integration.

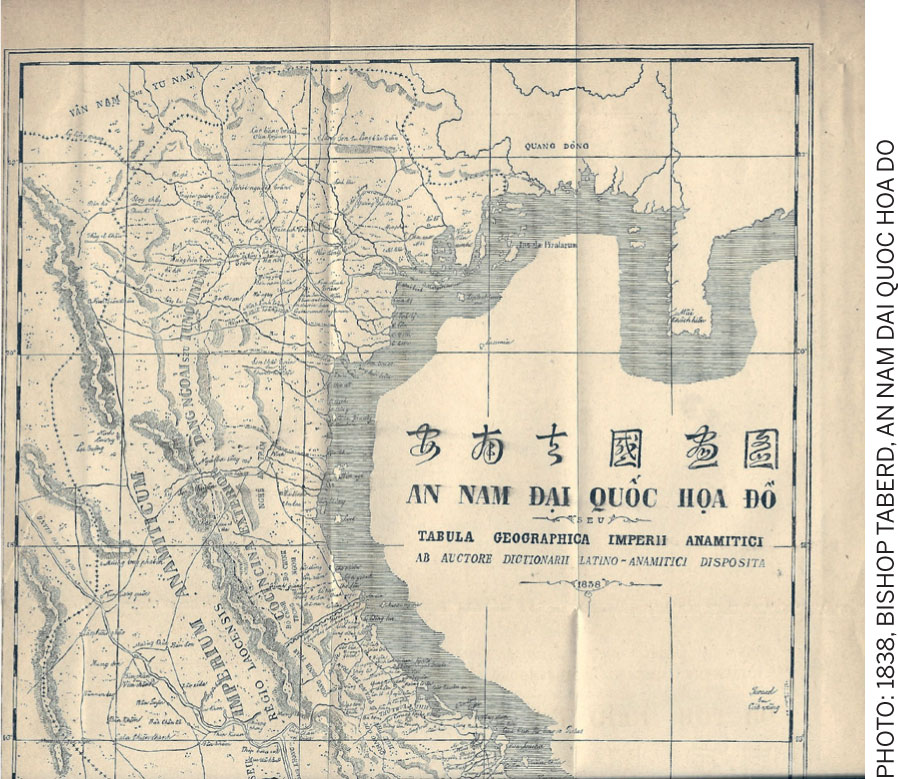

As Vietnam developed its governmental stronghold in Hanoi in the 11th century (Ly Dynasty), communication routes were an essential component of control. By 1471, the Duong Thien Ly/Duong Cai Quan (known as the Mandarin Route) was established by the Le Dynasty, which connected Hanoi to Binh Dinh (the then southern boundary of the country and presently in the centre of Vietnam). As the ‘main road,’ it was initially only allowed to be used by horse-riding Mandarins (government administrators who passed a rigorous exam) and was primarily used for the delivery of official documents (pre-empting the modern postal service).

In the reign of the Nguyen Dynasty (1802-1945), not only was the route significantly expanded, but a host of other infrastructures were also developed. Emperor Gia Long (reign 1802-1820) rebuilt the route to span from Nam Quan (at the northern border of China) to Ca Mau Peninsula (the tip of the Mekong Delta in the south).

The Route was known for its spectacular scenery through the nation’s highly varied landscapes, crossing river basin after river basin, dominated by steep rivers, besides the long plain and the majestic Red River and Mekong River deltas. It was considered the national economic and governance backbone.

South of Hanoi, from Thanh Hoa to Ho Chi Minh City (1400 kms) the Route is within 20 kms of the sea. Its highest point is Hai Van Pass (79 km north of Hue and 490m above the sea level), which today overlooks the sprawling metropolis of Danang and its huge harbour.

During the French colonial era (1887-1954), the Mandarin Route became the major artery and was called Colonial Road No. 1. Thereafter it was named National Road 1A (QL1A and was also known as Highway 1); it is 2301 km long, linking the northern Huu Nghi border station to Cape Ca Mau in the south. To this day, it remains both the primary north-south linear link as well as the vibrant core of everyday life for the settlements it bisects. The long north-south road, originally an expansionist project, and then a colonial endeavour, literally became a nation-building project, connecting and uniting against the sense of geography, a juxtaposition of different river basins that are roughly oriented west-east (which is a more natural orientation of movement). This counter-geographical nature of the ‘national highway’ might be emblematic for an engineered mastering of nature. However, its forcefulness as the prime national movement corridor is paralleled by scenes of everyday life that engulf it, lie beside it and across it.

Coalescence of scales and simultaneity of functions (and connecting and collecting to begin with) is what characterises most of Vietnam’s primary infrastructures. At the moment, as the ‘global village’ has become another layer of Vietnamese urbanity, the Mandarin Route has retained a significant part of its identity. Today, a journey down the QL1A route is indicative of Vietnam’s development, namely that its hybrid urban landscapes are the result of a stratified development process. The odd mix of romance and consumerism, liberty and conformity, connection and collection, hope and despair confirm that the country continues to be a place of extremes.

The ingenuity born of necessity has been translated in urbanistic terms to an ambivalence that imbues the street as an unmatched public realm.

Appropriated version of modernity

The French era brought a distinctive mode of European planning and urban morphologies to Vietnam. French urbanism pervades most of Vietnam’s larger cities and according to post-colonial scholar Gwendolyn Wright “the taste for extravagance which characterised both Hanoi and Saigon... earned the derogatory appellation ‘la folie des grandeurs’....(and) at a rudimentary level, the enterprise paralleled the contemporary work of Haussmann.” Large tree-lined boulevards mark a strongly identifiable form of tropical urbanism. One could argue that in this form of tropical urbanism, the boulevard space with its monumental (and relatively fast growing) trees is the primary urban frame with the adjacent parcels, complete with gardens and buildings, the secondary urban structure. Where in Hausmann’s Paris, the boulevard space and building are more-or-less equal to each other, in the tropical variant, the buildings were, surely during colonial times (and today too) relatively modest in size (since hygienic concerns anyway dictated large distances between buildings for ventilation, but also because, all in all, the building programme of the French was not overwhelmingly significant).

|  |

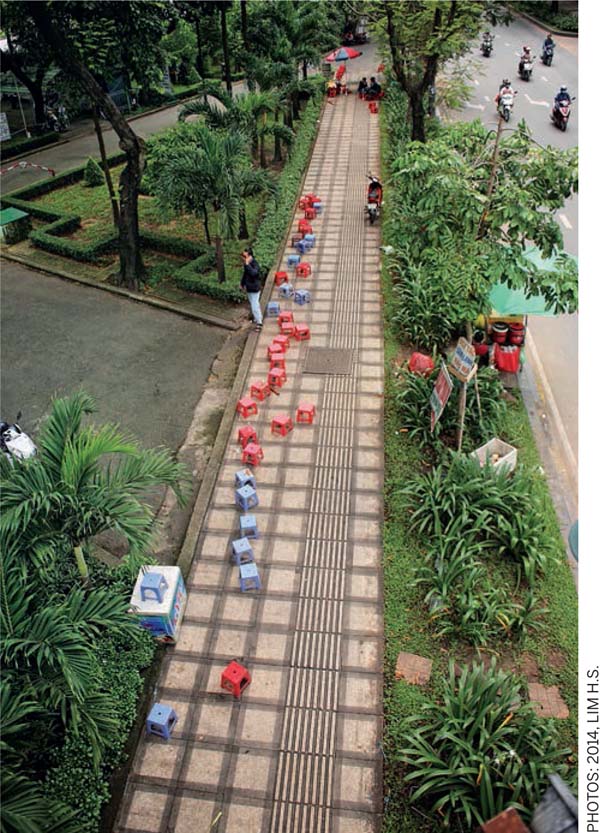

Therefore, it is the ‘disproportionate’ vastness of the boulevards and the monumentality of their plantation with trees that makes the city, more than anything else. The boulevards then become an ‘organised, cultured natural space’, simultaneously a space of fluid movement (which ultimately is what colonialism is all about—moving through the territory to control it) and a space to stand still. A shadowed, sheltered space to go through and to be in. For both roles, it was originally oversized. The oversize was evidently intended to impress, but at the same time it allowed for massive appropriation, both formally and informally. The boulevards became urban stages for so much to happen, so many different roles to be taken up simultaneously without disturbing movement. The boulevards are spaces of clarity and oversight where one can be both part of the whirls of urban life and withdrawn from exposure behind and between the trees.

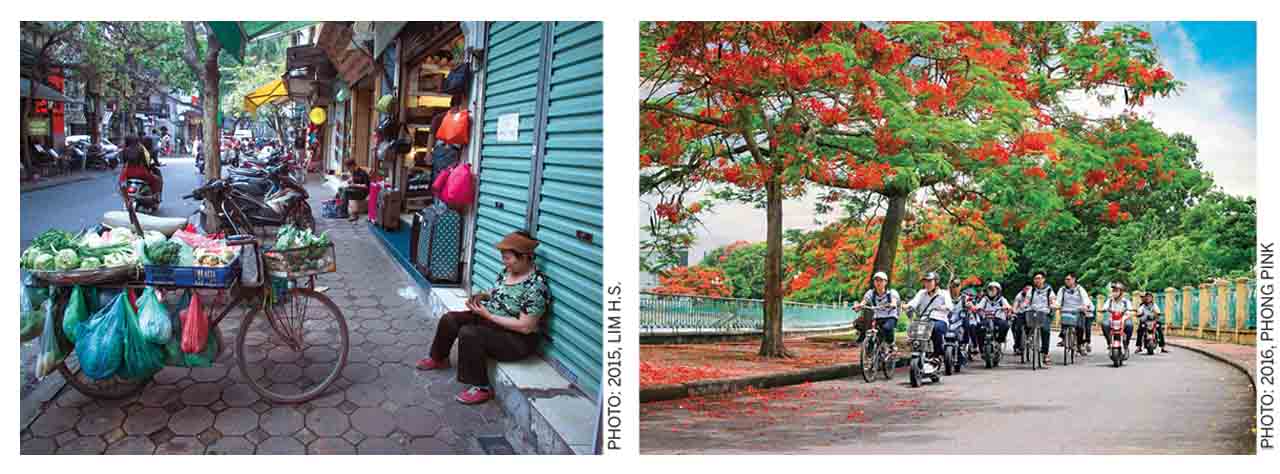

Over the course of history, there have been a host of other building traditions including Chinese, Cham, Japanese, American, East German and Russian that have been brought to the country. The current Vietnamese ‘tradition’ still reproduces some of the East German and Russian urges for the monumental, while absorbing the whims of the day through a relentless pursuit of urbanisation that replicated models such as Singapore, Shanghai and Seoul. Indeed, both the persistent force of tropical nature and the inventiveness of the Vietnamese population transformed and continue to transform external influences. Hybridisation has not been so much the exception as the norm. An innate informality prevails as evidenced in the public realm of sidewalks that coincide with an intimacy and dynamism of temporary semi-private claims for areas affronting households and businesses. Public passage has to compete for space with games, motorcycle parking, outdoor seating of restaurants and even ‘living room’ extensions. This competition — or perhaps a negotiated form of sharing — evolves over the day and night and with various seasons. Streets in Vietnam are truly urban living rooms, continuously, rhythmically and fluidly, adapting to the (needs of the) moment. The streets are a reverberation chamber of urban life, collecting the ‘cris de la rue’ (the cries of the street).

Beyond the sidewalk, different infrastructures, for reasons of convenience or purely out of necessity, have become what is sometimes characterised as polysynthetic constructs, new hybrid constructs that are not only more than the mere sum of their civil construction parts, but also acquire a civic quality.

They become what Lewis Mumford approximately 70 years ago labeled as ‘poly-technic’ — combining different technical devices with a transcendental role as public space; they are open signifiers that allow for a variety of practices, appropriations and subversions.

Separate mono-functional devices that generate the infrastructural landscape don’t necessarily lose their role, but are simultaneously part and parcel of a larger multitude of uses and practices that flourish by inverting, adverting, circumventing, subverting or otherwise reorienting the original intentions, codes and rules. Throughout Vietnam, the use of infrastructure is multiple — for informal economic activities, for drying aqua and agricultural products and for recreation.

|  |

Asian tradition of street trees

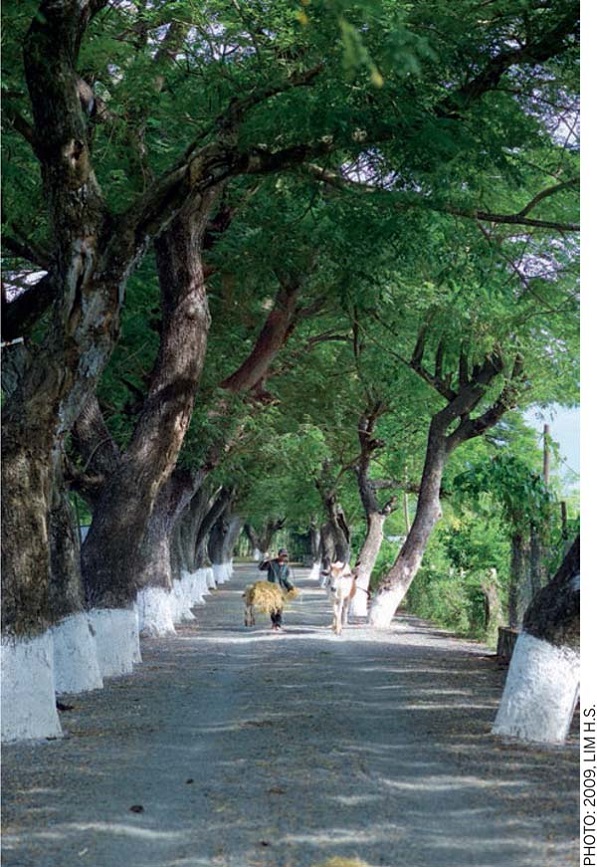

Tree planting has a long-standing tradition in Asian cities and specifically in its tropical cities. In many parts of Asia, cities historically developed in relation to a worldview that included geomancy (feng shui or phong thuy, in Vietnamese) and divination, which limited the activities of man; beliefs in land gods, river kings and forest spirits were both practical and mystical. In the tropical mountains, various ethnic groups carefully embedded their infrastructure and settlement types into the forests. In urban areas, trees were systematically planned and constructed at the national scale, first organised directly by emperors and later by central and municipal governments. Tree planting was not merely developed in tandem with mobility infrastructure, bus also occurred along riparian corridors in relation to flood protection and soil erosion. Initially, the Mandarin Route was planted to provide separated royal passage, shelter against wind, provide shade, protect roads from flooding and perform specific visual functions. Many of these notions have been carried on through the non-imperial systems that followed.

The legacy of tree planting from Imperial times continued during the French colonial era and so did Russian-styled socialism as contemporary national campaigns.

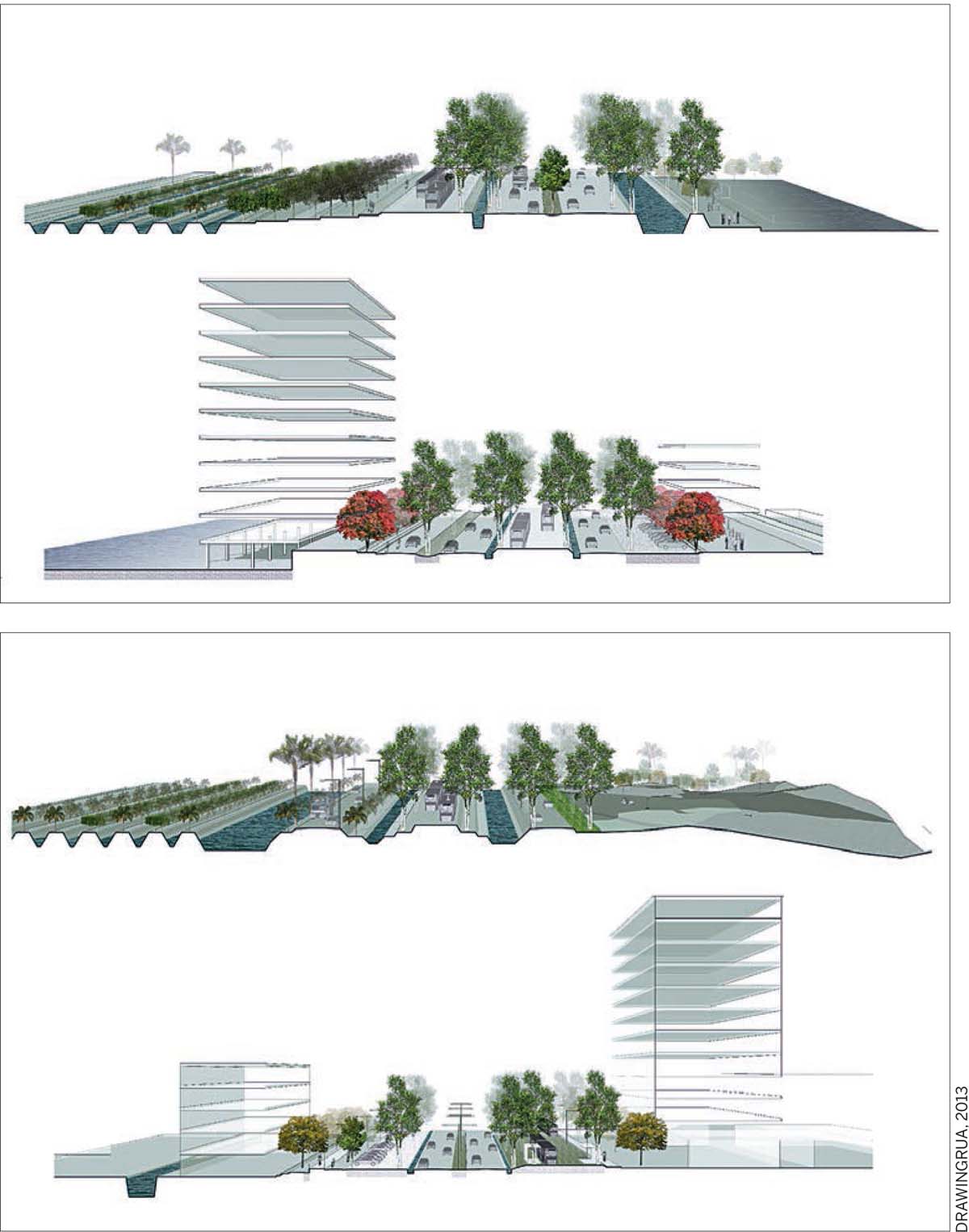

It must be noted that, at the same time, in both Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, there is a threat to a number of mature trees which are being illegally (for wood) and legally cut down for construction of subway and highway projects. While old trees are under threat (and their eventual replacement is often contested due to the nature of less valuable species for replanting), new urban areas (as for example in Saigon South) excel in the re-invention of generously sized and abundantly planted boulevards, where the sectional variations accommodate a variety of uses: attribution place to various contemporary needs (motorbike parking included).

Leap-frogging to the post-petrol and climate change era

Movement has always structured settlement and the domestication of territories by mobility infrastructure is driven by the fact that accessibility lies at the root of development. Urbanisation is premised on new economies, proximities, and hierarchies are disclosed by mobility. Throughout history — via carriage paths, railways, trams and roads — mobility infrastructure either merged with or brutally transformed the landscape to create vessels of collective life and drove modes of consumption and production. Today, the worldwide social production of movement is being radically transformed by diverse new mobilities since we are on the cusp of a paradigmatic shift in physical mobility. This, in turn, will fundamentally transform the built environment and generate novel spaces and temporalities.

Right: School children in Haiphong commuting on bikes and e-bikes under Delonix regia trees

As the post-petrol age beckons, a number of forces are coming together, namely technological developments on vehicle autonomy, vehicle sharing, vehicle electrification, alternative personal transport (e-scooters, self-driving pods) and the integration of renewable energy resources. These are complemented by concepts of shared economies/mobilities (that are facilitated by smart IT that allows bringing, offering and demanding instantly in direct contact, pool and redistribute) and increased investment in public transportation. The convergence of new shared mobility services with automated and electric vehicles will offer more transportation choices, greater affordability and accessibility, and eventually contribute to healthier, more liveable cities, along with reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Already today, alternative transport modalities, such as the Singapore app-based ride hailing Grab (for both cars and motorbikes) is becoming more prevalent, not only as a complement to the first/last mile for public transport, but as well as for food delivery service. As a pool-platform for ride sharing, it formalises to a certain degree existent flexible and informal motorbike taxi system, while expanding its reach and increasing efficiency.

In Vietnam — which for the past few decades has engaged in a comet-speed catch-up game with modernisation and globalisation after its relative degree of political and economic isolation, stagnation and destruction caused by decades of war and its political aftermath — there remains a closing window of opportunity to literally leapfrog over the obsessive fury of investment in traditional road-based infrastructure building. Due to the massive air pollution brought by a surge in vehicular use, the government is making major investments in public transportation. At the same time, in recent years, electric bikes and electric motorbikes have become increasingly popular in Vietnam. Already in 2012, the government showed interest in promoting electric vehicles (EV) in its national policy and in 2013, e-bikes accounted for 14% motorcycle sales. The largest group of users includes primarily students and the elderly; an additional advantage to their clean emissions is the fact that they cost far less than their petrol-guzzling cousins. A brand new Vietnamese model sells for around $ 325. As such, IT is becoming an important infrastructure that allows a fundamental shift in thinking about mobility as is already emerging in practice.

Today, one can already fluidly jump from a Grab to a metro and vice versa: order a Grab just in time when leaving the subway, bus, restaurant or office. A new division of labour between offers, including organised forms of public transport and demand-steered forms of IT-supported sharing services will surely revolutionise the mobility of the 21st century cities-in-the-making in Vietnam. In turn, the mobility revolution will greatly impact the built environment and its use, to begin with the opportunity afforded by the re-profiling of oversized roads, ripe for ‘shifting lanes’ and transforming use.

Comments (0)