Provision of social housing for the poor on a government subsidy is the most challenging problem facing the global urban condition today. Effective solutions are scarce and much work needs to be done for a long-lasting impact in the urban environment. More importantly, ‘out-of-the-box’ ideas that challenge the status quo and demonstrate new attitudes to problem solving are the need of the hour.

The problem is so widespread and the challenge so daunting that most architects and designers either shy away from this challenge or work with the problem in a disengaged manner.

However, the work and ideas of Elemental, a group from Chile, has been seminal in addressing the complicated questions and challenges that face housing the poor in our cities. Their work and ideas on incremental social housing strategies over the last decade in several South American cities has, with repeated success, demonstrated new ways to resolve and engage with this issue.

Though the concept of structure and infill solution as a means to provide stable and incremental models of social housing is a well-established idea, Elemental’s understanding of the challenges has been unique; that the biggest challenge in such projects is the initial capital cost of land and construction. So, rather than adapt the obvious solution of relocating the community to the periphery of the city where land is cheap in order to provide a bigger dwelling,

Elemental propose to rehouse the families in their existing location. Thus, maintaining the communities’ well established socio-economic networks, which form the backbone of the concept.

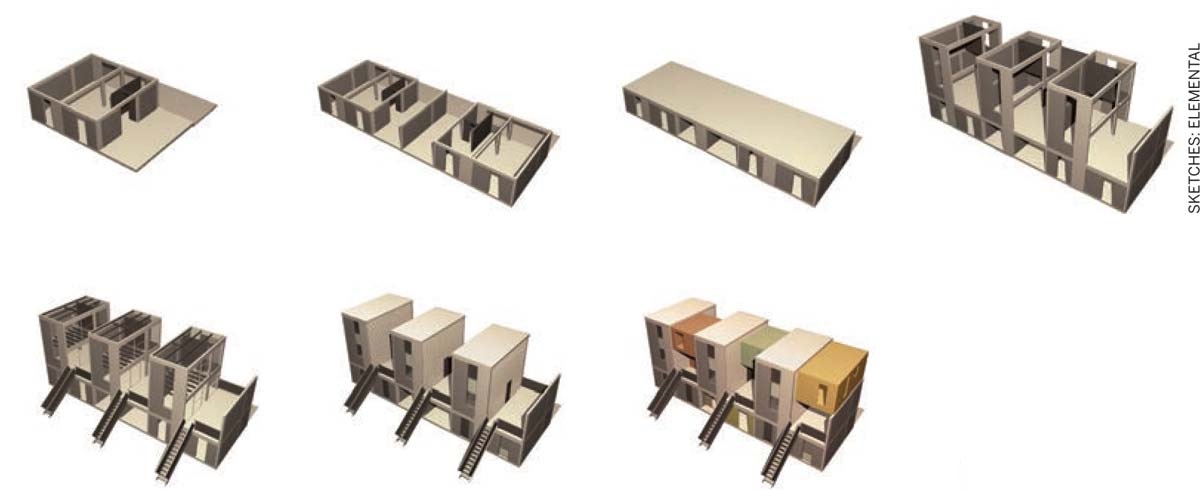

Furthermore, avoiding relocation makes the subsidy-based project by the government an investment into social housing by making it an ‘appreciable asset’ because of its central city location, an important quality for its sustenance in the future. Lastly, Elemental’s concepts are based on the idea of infill solutions, which they aptly call ‘half of a good house’. Since maintaining the land parcel within the city costs much more in terms of land value only smaller/inadequate sized houses can be built within the prescribed government budget, these are ineffective for future growth of the community and family. However, Elemental proposes design solutions that provide half the adequate area immediately along with the basic framework in order to add the other half in progressive increments by the homeowner based on their resources over time. It provides complete flexibility to adapt a house on the basis of the family’s demands. To solve complex housing equations and yet design for flexibility within the preferred community context, within government prescribed budgets and making the community a stake holder in its future development is a unique proposition at multiple levels. It is an exercise in learning how to conserve, adapt and prioritise the immediate needs while proposing social housing ideas in the heart of the city thus maintaining the city and its future as an opportunity for all economic classes.

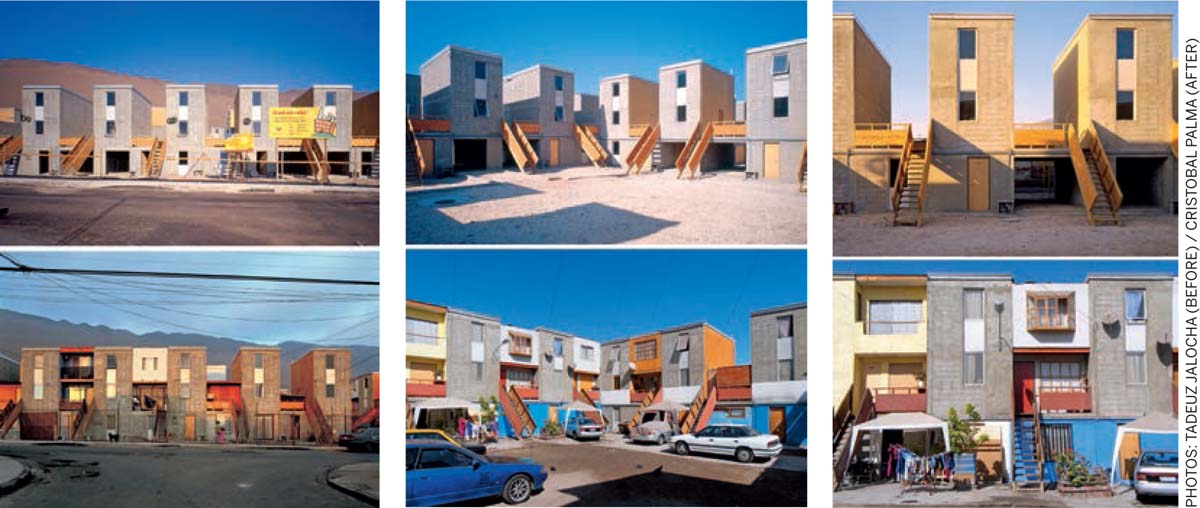

Quinta Monroy, Iquique - Chile, 2001 - 2004

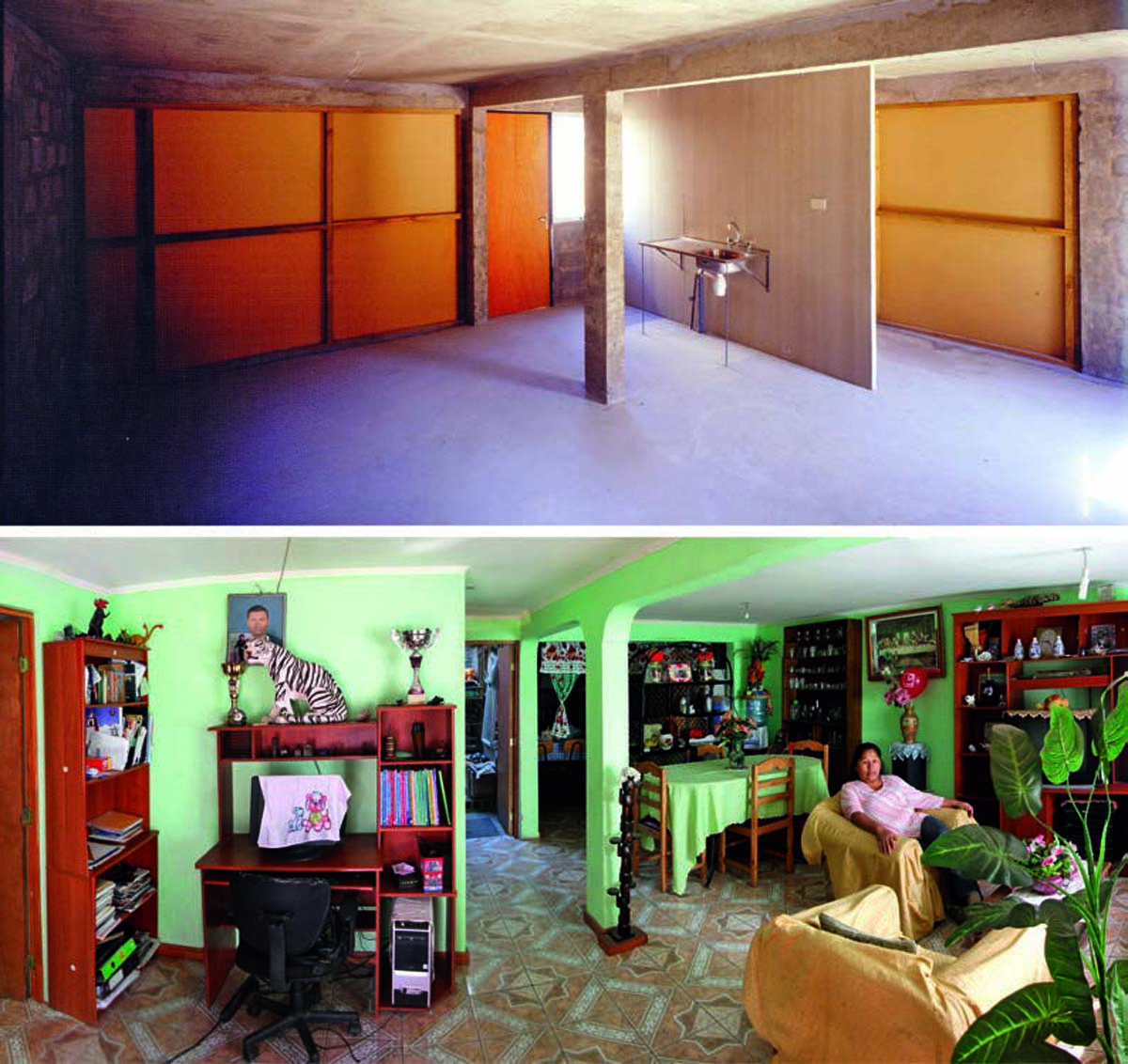

In the case of Quinta Monroy in Iquique, Chile, the equation was challenging. How do you provide social housing on a $7,500 government subsidy (cost of land + house) per family for 100 families who were squatting on half a hectare of land in the centre of the city for 30 years? To make houses in that budget meant providing a 40-sq.mt. size of dwelling unit after reducing the cost expended on buying the land. Such a size was inadequate for growth. However, looking at the problem from an incremental standpoint of providing the essentials and designing for the growth is what made Quinta Monroy the first successful prototype of the ‘half of a good house’ philosophy. It has provided 93 dwelling units in two typologies. Rather than provide separate houses on lots which would not achieve the desired density on the land, or a high rise typology which would provide land efficiency but no possible flexibility for the future, Elemental proposed a prototype that provides horizontally interconnected units at two levels (a duplex unit sitting over a ground floor unit) with equal amounts of built and open voids in the middle for future expansion without overcrowding and providing the same quality of light and air in the expanded unit. Units provided on the ground floor have potential for lateral expansion on the ground on two sides and duplex units on the upper two floors have potential for lateral expansion on one side at two levels.

PHOTOS: TADEUZ JALOCHA (BEFORE) / ELEMENTAL (AFTER)

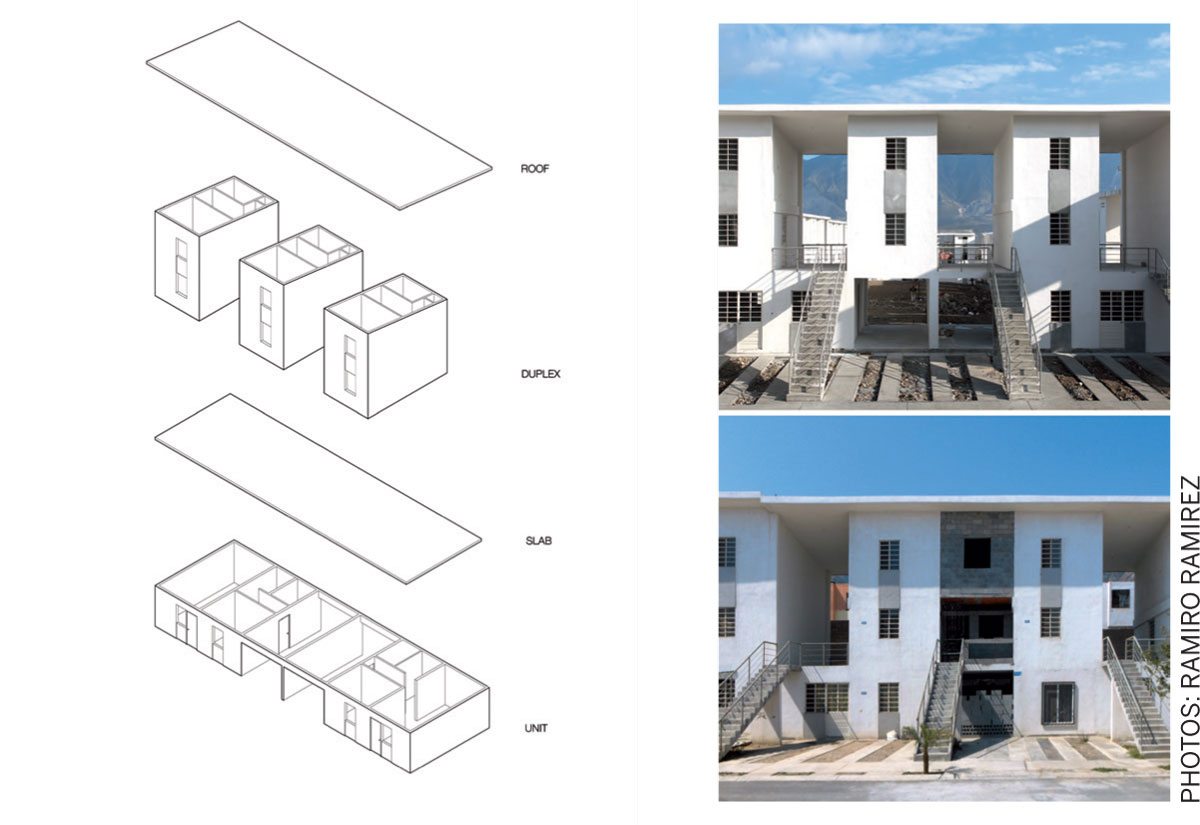

Las Anacuas Housing in Monterrey, Santa Caterina - Mexico, 2008 - 2010

Right: The Las Anacuas development: Before and After the residents moved in

A similar experiment in a different climate type at Santa Caterina in Mexico was designed keeping in mind the rainfall the city receives during the monsoon months. While replicating the Quinta Monroy typologies, a large continuous overhang roof was designed to facilitate the expansion during all seasons so as to keep feasibility of expansion through construction intact.

In the last decade Elemental has provided more than 2000 dwelling units with these progressive urban social housing strategies. And though it should be noted that there are more challenging countries in the world like India and places in Africa that don’t have effective policies for social housing subsidies and are dealing with far greater challenges of densities and budgets, the primary ideas of Elemental’s work are extremely relevant to all parts of the world. The skill to provide a decent, equitable and affordable future in our cities for all, by way of design, is a universal requirement and once again provides the opportunity for the architect to become relevant towards our most demanding urban challenges.

PHOTOS: RAMIRO RAMIREZ

In conclusion Alejandro Aravena, the founder member of Elemental sums it up well in an excerpt from an interview in The Guardian: “One of the biggest mistakes in architecture is that we’re expecting society to be interested in the specific problems of architecture. Instead, architects need to adjust to what society is discussing. We just provide the forms that can translate their problems into solutions.”

Comments (0)