The main elements of the transformation process of the modern Latin American city should be understood as the influence of European urban ideas that in general were transferred in a sui generis fashion to the Latin American metropolises at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century (Almandoz 1999). Venezuela shares a similar history to other Latin American countries, where the prevailing settlement pattern and culture was the result of the widespread Spanish colonization process. However, the case of Venezuela differs regarding its urbanisation process because of the accelerated urban growth rates mainly triggered by the discovery of oil in 1917.

Urban population growth in Venezuela is considered to be amongst one of the most rapid in Latin America. Much of this growth took place in the capital city of Caracas. Two main factors were responsible for the urban transition: the first being the drastic change in the economic base of the country from agricultural production to mining and oil exploration. The second reason was the subsequent need to develop the service sector in order to sustain the new oil industry.

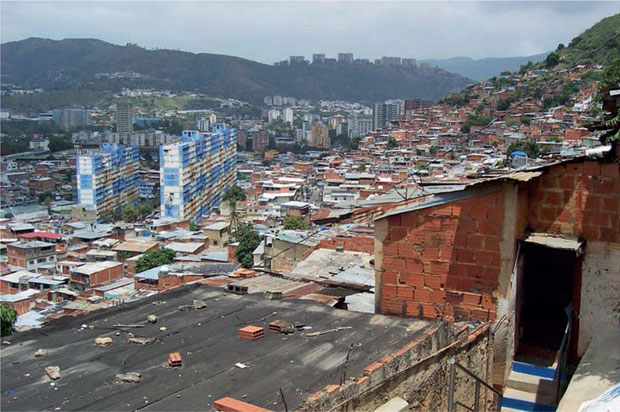

Rapid urbanisation brought about urban poverty and a steady deterioration of urban living conditions for a majority of people. The urban growth of the valley of Caracas during the 20th century led to the densification of informal settlements which, according to Harms (1997) can be explained by a number of interrelated factors: (a) the difficult topography of the valley restricting access to urban land; (b) the global city effect highlighting the demand for office space, which in turn increased the value of land thus having a negative impact on land development for residential purposes; (c) the modernization process along the lines of development in North American cities, which led to social and spatial segregation within metropolitan areas; and (d) the changes in the relationship between the centre-periphery, in which urban sprawl increasingly outstretched the periphery from the centre, thus creating new centres around which informal settlements grew and consolidated.

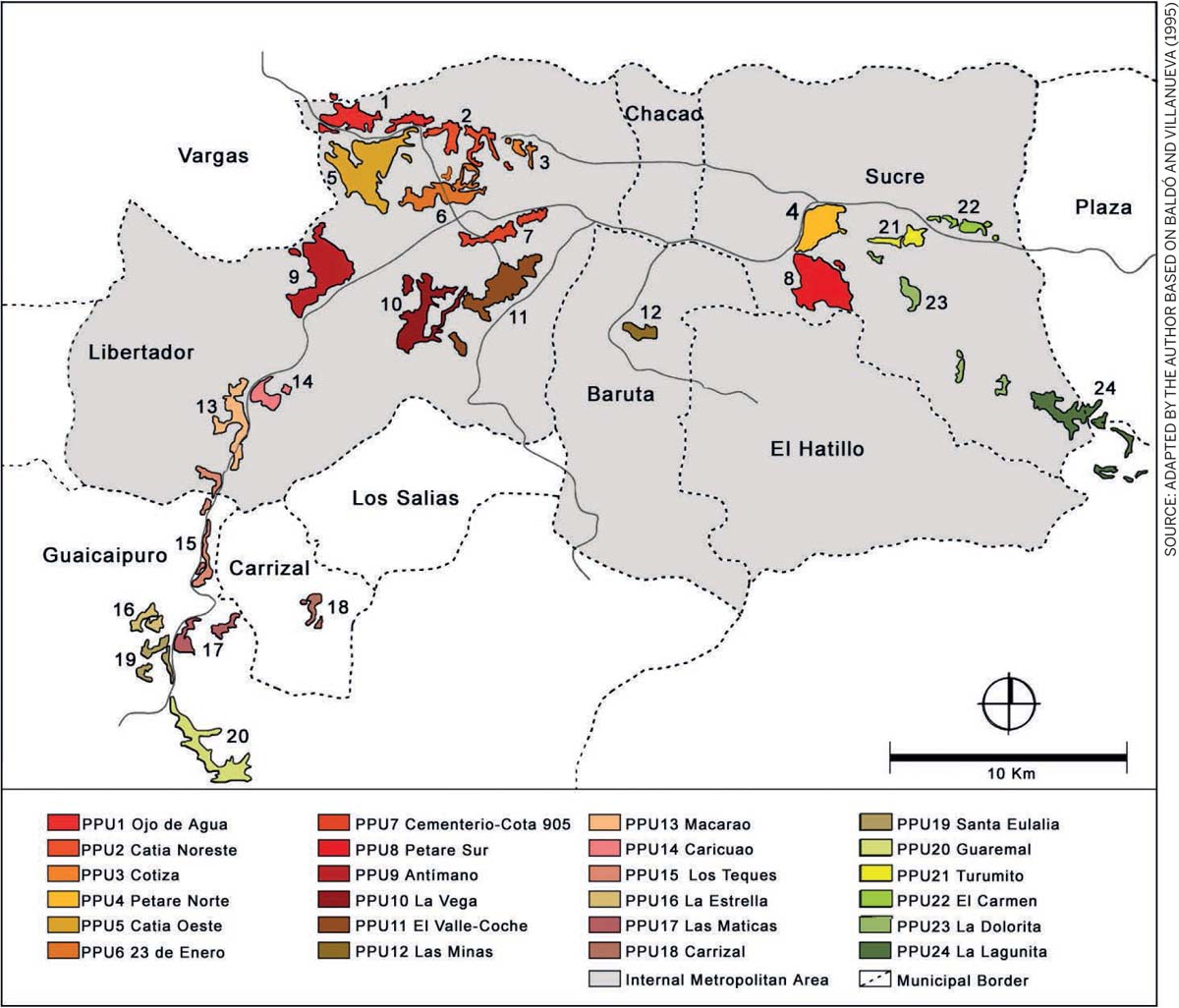

By the end of the 20th century, 40.7% of the total population of the country (8,738,000 inhabitants) was living in informal settlements, known in Venezuela as barrios.

Such figures give a clear indication of the scale of the problem since it is in barrios where poverty concentrates and inequalities are most evident. In Caracas, 55 per cent of the population lives in barrios occupying 33.5 per cent of the city’s area (UN-Habitat 2006). Currently, the situation has not changed much and informal urbanisation continues expanding due to natural population growth and rampant poverty.

Poverty, social exclusion and spatial segregation of barrios

Geographical segregation is an extremely powerful mechanism of exclusion with significance that exceeds material deficiencies. The barrios in Caracas offer a socio-spatial laboratory of exclusion and segregation. Characteristic of the exclusionary process experienced by the poor in Venezuelan society is their low self-esteem, which emphasises the difficulties of carrying out self-help projects. Moreover, low self-esteem forms a powerful barrier to social organisation. In this way, the State is able to continue exercising its paternalistic approach to social development (Barroso 1997).

A great number of households in Venezuela are affected by exclusion.

Between one quarter and one third of the population suffers from an extreme degree of exclusion concerning their right to education and health. These access rights to the social entitlements of education and health, as well as the preservation of individual rights, are strongly related to space, as the link to geographical segregation is very strong. Only about a quarter of the homes where the poor live are adequate in the sense of having minimum space and service connections meeting national legal standards (Cartaya 2007).

A household whose situation might lead to escaping poverty is strongly inhibited by being part of these segregated spaces. Venezuela is characterised by a gap between what the Constitution defines as social rights and what its constituencies experience in their everyday lives.

Barrio: definition, formation and consolidation process

The origins of barrios in Venezuela date back to the beginning of the 20th century. They were not only the result of uncontrolled rapid urbanization processes that arose following extensive rural-urban migration, but they were also the consequence of an incompetent public housing sector. The first barrio was already being settled in 1917.

There is universal agreement that poverty is related to the lack of or a precarious access to basic needs, poor economic opportunities and subsistence livelihoods. Considering that poverty is widespread in informal settlements, these can be defined as precarious residential areas with poor access to basic needs, formed by households living under acute economic constraints, with people experiencing social exclusion to varying degrees and spatially concentrated in distinct parts of the city, which are environmentally vulnerable and not suitable for housing purposes. Several other forces influence their already negative socio-economic and spatial conditions. These are mainly social stigmatisation by outsiders, ambiguous citizenship underlying weak political participation and an illegal status stemming from occupying land they do not own (Ayala 2012).

Barrios are commonly built on public land through organised ‘land invasions’, which is a common feature of informal settlement processes in Latin America.

They evolve through a gradual appropriation of land and incremental shelter growth. In many instances, barrio formation has been supported by political proselytism and the patronising structure of government institutions, which has a clear goal of gaining votes through a permissive attitude towards informal land occupation.

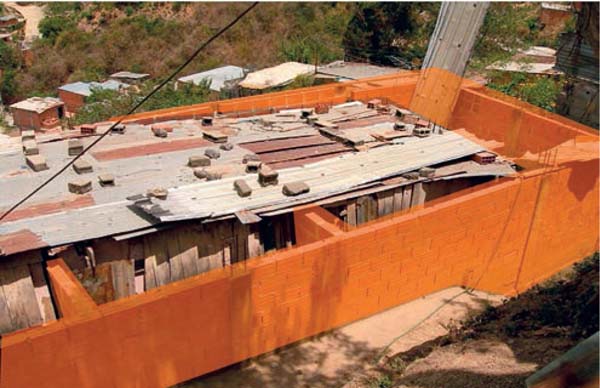

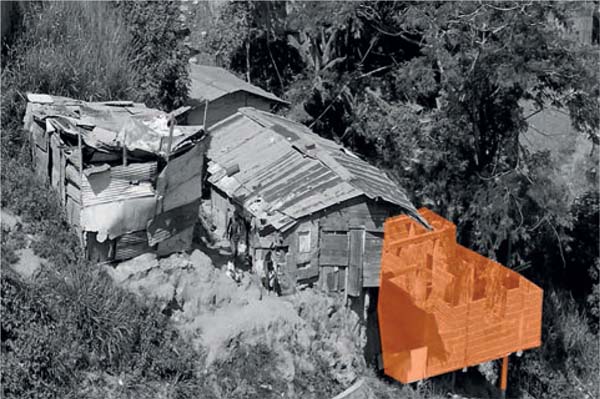

The rancho is the name given to the initial shelter structure built in barrios that a pioneering settler or newcomer to the barrio is able to afford. As the household’s socio-economic conditions improve, so does the original dwelling unit until it is transformed into a solid, permanent structure. The consolidated house results from the adoption and interpretation of the widespread building technology of the city (i.e. reinforced concrete structures with brick walls) and the culture of the barrio inhabitant (reinterpretation of some architectural elements of rural houses). The use of the aforementioned building technology, irrespective of its structural integrity, is indicative of the consolidation of a barrio. The higher the number of shelters transformed into solid concrete and brick houses, the greater is the consolidation of the barrio. Housing structures built this way can sometimes reach up to six stories.

Following long processes of consolidation and social cohesion, barrios have become part and parcel of urban life, interacting with the city despite their unclear legal status and their incomplete socio-political and spatial recognition. The barrios of Caracas are strikingly visible, constituting a major feature of the city’s landscape. They are too large, well settled and consolidated to be dismissed as marginal, or as an exception to the rule.

The incremental process of house construction: Innovative ways of dealing with house construction and consolidation can be seen in these figures | |

|  |

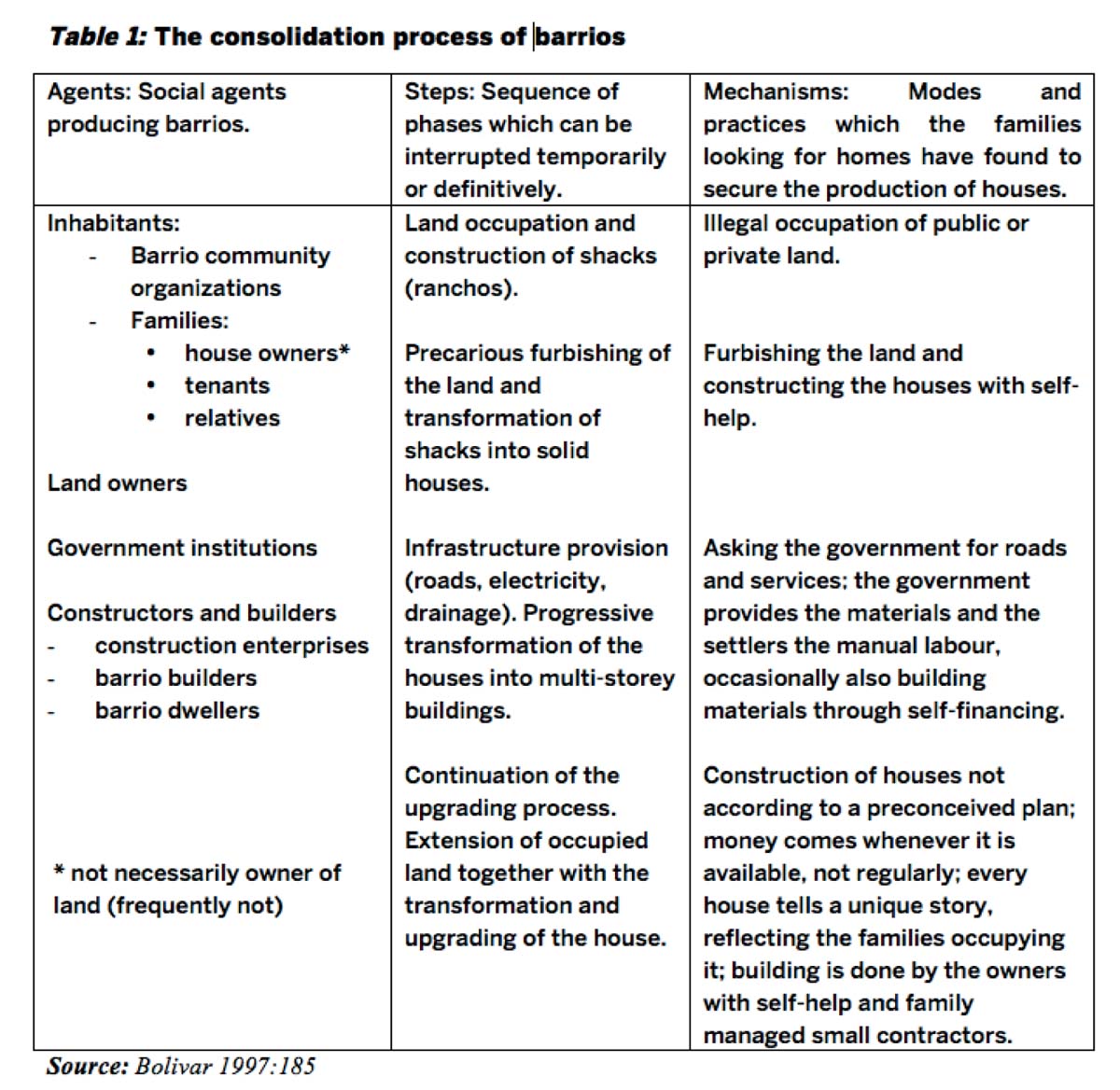

Table 1 shows the social agents, steps and mechanisms involved in the production of barrios, highlighting the different stages of the consolidation process.

In sum, Venezuela’s poor tend to settle in the only areas available to them, the city’s informal settlements. Once they become inhabitants of these areas, they experience a structural lack of access to the services and opportunities needed to improve their lives. Under these conditions, geographically concentrated poverty continues to grow in Venezuela’s urban areas, acting as both the driver and the outcome of barrio formation and consolidation (Ayala 2012).

Expanding the meaning of barrio: Legality vs. illegality

At this point, it is important to discuss the current legal standing of barrios in Venezuela, as they sit at the nexus of two opposing forces: one focusing on their status as illegal settlements and the other focusing on their economic and political contributions to the city, leading to the creation of legal frameworks for their integration, regularisation and upgrade. These opposing forces are visible throughout Latin America, as it is common for settlements established on illegally settled land – through land invasion or infiltration, for example – to gain tacit approval from the state, often for political reasons.

To reprise the discussions made thus far on barrio illegality, they are located in areas of the city that have not been developed by the formal public or private sectors, often due to conditions such as steep slopes and environmental hazards. Their illegality stems from the fact that the underlying lands have been settled without the benefit of legal titles and without legal permits to do so.

The condition of illegality extends to the status of the residents themselves, many who do not have clear citizenship and several who work in the informal economy outside the scope of regulation and taxation. In some of Venezuela’s barrios, the residents are faced with overt threats of eviction and eradication of their homes, or they are faced with more subtle threats such as the long-term denial of services.

At the same time, the residents of other barrios in Venezuela feel relatively secure, given the advanced state of consolidation where they live and the possession of semi-legal documents stating that they own the physical structures they have built atop the illegally settled barrio lands. These semi-legal documents formed the base for renting out and selling houses in the informal market.

The reality is that barrios make positive contributions to the city in Venezuela: they provide a source of low-income housing as well as additional producers and consumers for goods and services. They function to complete the urbanization process, developing communities on the last vestiges of urban lands that have been left undeveloped by others. Barrios also contribute political capital to candidates who may pander to the plight of barrio residents in order to win additional votes and support for their political campaigns.

While legal frameworks and initiatives to improve the living conditions of barrio inhabitants have been tried throughout the urban history of the city, they have not resulted in significant improvements in the quality of everyday life on the ground. Overall, it is clear that a mosaic pattern exists today, encompassing steps toward legality for some ‘suitable’ barrios, alongside the continuation of illegality for other ‘high-risk’ barrios, as well as steps toward legal inclusion, alongside the continuation of social and economic exclusion.

The urban transformation of Venezuela, epitomized by the drastic demographic change of the once provincial city of Caracas into an emerging modern metropolis at the beginning of the 1950s, represents a unique example of rapid urbanization in Latin America.

Urban Venezuela is the result of the discovery of oil, which eventually cursed the country as an oil-fed and oil-dependent economy and society. The gradual decay of Caracas coincided with a dramatic process of rapid urbanization under poverty. As a result, Caracas is characterised by fragmentation and the segregated settlement patterns of its social groups.

The conflicting political situation over the last 20 years has created an additional urban burden on previously unsolved problems. Today, political autocracy and social polarisation exacerbates social exclusion processes and the negative effects of spatial segregation. The rise in inequality indices, increasing impoverishment of the middle class, rampant poverty levels and spatial consolidation of social exclusion in barrios is a distortion of what should be urban development. This is an issue that needs urgent intervention. The case seems to be of an inability to learn from past experiences. Before the establishment of the current dictatorship that has sunk the country into a socio-economic and humanitarian crisis, previous governments drew up poverty reduction strategies with short-term perspectives. Interventions were punctual, often manipulative and often full of vested economic and political interests. They frequently aimed to mitigate the negative outcomes of poverty rather than address the root causes. Therefore, compensatory programmes persisted, political fraternities reigned and populism and paternalism were the order of the day, with no sound structural changes being foreseen.

As the middle classes suffer from downward mobility and tend to disappear, thus joining the poor, so also does polarisation and inequality in the country increase, resulting in a society made up of an extremely rich minority and an extensive heterogeneous poor sector. This distorted situation poses a threat to the development process of the society as a whole.

References:

•Almandoz Marte, Arturo (1999): Transfer of urban ideas. The emergence of Venezuelan urbanism in the proposal’s for 1930´s Caracas. In: International Planning Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 79-94.•Ayala, Alonso (2012): Urban upgrading intervention and barrio integration in Caracas, Venezuela. PhD dissertation. Geographische Grundlagen und Raumplanung in Entwicklungsländern, Fakultät für Raumplanung, TU-Dortmund. •Baldó, Josefina; Villanueva, Federico (1995): Un plan para los barrios de Caracas. Concejo Nacional de la Vivienda, Caracas.•Barroso, Manuel (1997): La Autoestima del Venezolano. Democracia y Marginalidad. Editorial Galac S.A., Caracas.•Bolívar, Teolinda (1997): Densificación de los barrios autoproducidos en la capital de Venezuela. Riesgos y vulnerabilidad. Red de Estudios Sociales en Prevención de Desastres en América latina. •Cartaya, Vanessa et al. (2007): Agenda para el Diálogo sobre la Pobreza en Venezuela. ILDIS. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn, Germany. •Harms, Hans (1997): To live in the city centre: housing and tenants in central neighbourhoods of Latin American cities. In: Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 193-198.•UN-Habitat (2006): State of the World’s Cities 2006/7: The Millenium Development Goals and Urban Sustainability: 30 Years of Shaping the Habitat agenda. Earthscan, London.

Comments (0)