In the history of urbanization, in countries around the world, cities have invariably gone through cycles of development. The process of industrialization and job opportunities in cities attracted large masses to these urban magnets for the chances they offered for economic improvement.

In various societies this led to different strategies to try to accommodate large populations in housing that has certain minimum basic qualities including basic infrastructure such as water, electricity and sanitation. The strategy adopted in each society depended on the societal circumstances present, the technology available and the role the government, and sometimes the civic society, was willing and able to play on the whole.

None of the strategies adopted can be seen as a panacea for solving the problem of providing housing for all; and while each strategy delivered some results, others could be used in combination.

In the Urban Blueprint section which follows, each strategy has been written about in more detail using an example. As one would expect, the examples are from different parts of the world. The strategies written about could be listed under the following categories:

1 Use of Industrialized Building: Techniques for Mass Production

This strategy has been used in different parts of the world including Eastern and Western Europe in the period after the Second World War when the industrialized production of building technology became available. The large-scale housing estates so produced, while often criticized for the lack of urban quality, continue to play an important role in housing large urban populations in relatively inexpensive homes. The article on Bijlmermeer in the Netherlands and Nova Belgrado in former Yugoslavia illustrates the result of this strategy.

This strategy of creating mass housing is still being used in more advanced societies such as Singapore, where social housing is a great priority of the government.

|  |  |

The most extreme in this philosophy is probably the Nakagin Capsule Tower in Tokyo built to the design of Kisho Kurokawa. Completed in 1972, the building is an example of the school of thought in architecture called Metabolism. Kurokawa designed the building with the intent to produce the capsules – units of 30 square meters as complete modules produced in factories – and to ‘plug-in’ the capsules and renew them every 25 years. The fate of this building hangs in the balance now as the technology used needs replacement.

2 Local Materials and Local Craftsmanship

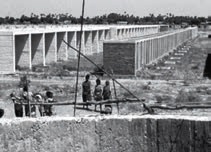

This strategy is based on the philosophy that the use of local materials and craftsmanship, which has evolved over the centuries, form the best basis for providing affordable housing that is sustainable while at the same time creating job opportunities for the community. This strategy, by its very definition, is the ‘other side of the coin’ of the earlier described strategy of Mass Housing through industrialization. Though the resultant numbers may be small, the results generally score higher on the scales of local identity through vernacular architecture, sustainability and overall beneficial effects on community development. Hassan Fathy’s New Gourna project in Egypt can be seen as one of the first projects in this direction. Articles on the work in Hunnarshala, Gujarat and Costford, Kerala are examples of this school of thought.

3 Support and Infill

The Dutch architect John Habraken (1962) introduced the support-infill concept in housing giving the user a clear domain of control, based on the concept of ‘open building’. According to Habraken’s theory, a large-scale supporting structure is built by the State/professional organizations, while the infill is thought out and built by the individual residents. This approach thus not only gives the resident the possibility of actually designing the inside of his house to his needs but, more importantly, building it when the funds are available over a period of time. The works of Elemental in Chile are recent examples of the results of the use of this strategy.

The incremental housing scheme at Belapur (Navi Mumbai) designed by the late Charles Correa may also be seen as an example of this strategy.

4 Site and Services

The strategy of Site and Services seeks to bring affordable housing within reach of the poor. The fundamental idea is to provide the residents individual plots, which have been provided with the basic infrastructure of electricity, water and sanitation and let the individual residents build and upgrade it as their financial capacity allows. In India, in the 1970s, the American-Indian architect Christopher Benninger was a consultant to the Madras Metropolitan Development Authority to realize a project at Arambukkum in Chennai.

5 Financial Engineering

An example of this is financial cross-subsidization as for example seen in the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme adopted by the MMRDA in Mumbai. This system of cross-subsidization has been used earlier in other societies too such as in the Netherlands, where affordable housing in the form of social housing provided by Housing Corporations has been partly also realized due to a system of cross-subsidies used in projects containing private sector housing and social housing.

6 New Technologies and Creative Design

|  |

New Technologies and Creative Design have often led to fresh perspectives on how housing can be built at lower prices and often in large numbers. In the middle of the 20th century, it was the promise of industrialized building technology and prefabrication.

The latest promise comes from 3-D printing technology that might open new perspectives for building in general and housing in particular.

The first 3-D printed house and bridge are already planned in Amsterdam. And the European Space Agency is exploring the possibility of establishing a permanent lunar base with the aid of 3-D printing technology. Whether this is ever suitable for creating affordable housing still needs to be seen. But the fact remains that creative use of new technologies even beyond 3-D printing, materials and design offer the hope for more affordable housing.

7 Short Term and Quick Response Solutions

Sometimes the demand for housing is for a short term, either due to the holding of an event that has a short time-span such as the Kumbh Mela in India where a temporary city is built to celebrate a religious event or due to an unexpected disaster, which leads to a human calamity like the recent earthquake in Nepal or the issue of housing large numbers of asylum seekers fleeing war zones. In all such cases the demands are for setting up shelter with lightweight, transportable elements, which are, as far as possible, also reusable.

8 Regeneration and Improvement

|  |

Regeneration strategies leading to value addition in affordable housing and improvement of living conditions is another strategy that has multiple interpretations. This approach has been used for example in the Espana Library project in Medellin, Colombia, where the new amenity was specifically placed in the crime-ridden barrio of Santo Domingo in order to help regenerate the surroundings. The work of Haas&Hahn described in their painting of an entire favela in Rio de Janeiro and including the community in that effort is another, if somewhat different interpretation, of the same strategy.

9 Creating New Towns

This is a strategy that has been adopted by several governments to (a) decongest existing cities where land prices were high or (b) open up new areas of the country for urbanization. An example of the first type is the many New Towns created around London in the second half of the last century, allowing affordable housing in large numbers to be built on relatively less expensive land.

Examples of the second category are the New Towns such as Brasilia in Brazil or Dodoma in Tanzania, where though the city was built with the intention of providing housing for large numbers of inhabitants, the affordability of the housing provided can be questioned.

The strategies listed above are some of the important ways of achieving affordable housing.

However, what remains important is the location of the affordable housing close to employment areas.

Since affordable housing far away from job opportunities, at the edge of the cities, will in fact be unaffordable in the larger picture.

Comments (0)