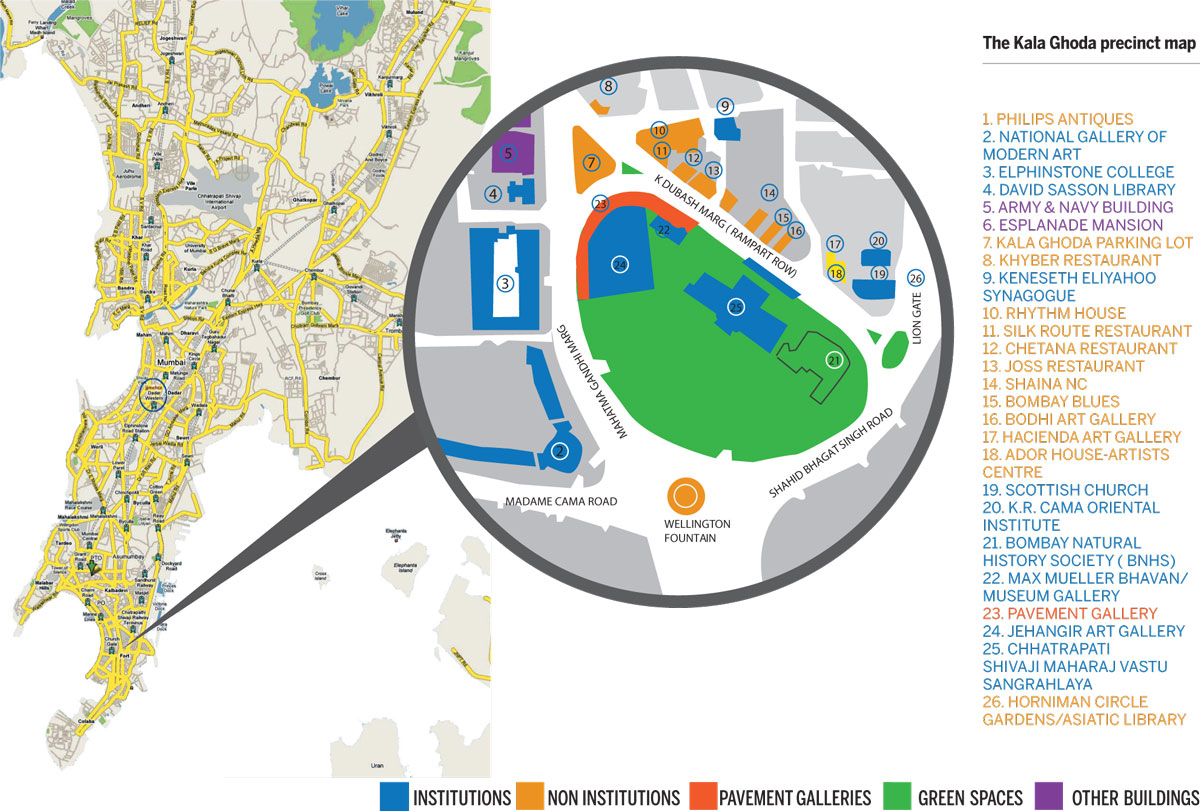

The revival of the Kala Ghoda precinct, an effort spanning over 15 years, is the story of vision and faith, of resilience and hard work, and of the strength of a committed few who stayed the course. The Kala Ghoda Art Precinct can be roughly defined as the area that stretches from the Regal Circle at the southern end of Mahatma Gandhi Road, up to the Mumbai University and further north to Horniman Circle, flanked by the Oval Maidan to the west and the Lion Gate to the east.

MLC traced the journey with Ms Brinda Miller, one of the trustees of the Kala Ghoda Association and who has been involved in the precinct’s transformation almost since inception.

In 1998 the Kala Ghoda Association (KGA) was set up by a group of cultural institutions and art galleries in the area who had a vision and saw a tremendous opportunity to create a very unique and vibrant art district in the busiest part of the city’s commercial district. At its core was the need to restore and conserve the heritage of the precinct and improve its physical environs.

But the area lay in the murky hands of drug peddlers, dingy bars, crumbling facades and the seamier side of the city. So, what did it take to transform a tired and forgotten precinct into a vibrant cultural hub, seamlessly blending history with the raw energy of a modern Indian city?

Garnering support of like-minded citizens and corporates, the KGA set about trying to activate the area with a small art festival. The Association recognised that the largest emerging interest in the area is art-related. Supported by well known artists with their time and artistic energy (MF Hussain composed one of his murals during one of the Kala Ghoda Festivals), the initial years saw the galleries and museums spill out onto the pavements, celebrating art and culture with the man on the street. Each year the KGA would hold the festival and never really know if the next year would happen.

The first 5 years of struggle saw the festival grow, until it became a 9-day celebration of art and culture, food and entertainment with multiple venues, both indoor and outdoor, and with an amphitheatre for the performing arts. As it grew, there was an increasing need for funds. Corporates and media houses stepped in with their support.

Each year the KGA diligently sets aside the funds needed for the restoration of the heritage buildings: cleaning the Elphinstone College facade and its illumination, the creation of an amphitheatre from a municipal shed for the cultural performances, restoration of Cama Hall, the David Sassoon library and garden, the Horniman Circle garden, the Institute of Science and the wall mural at Khyber restaurant.

As art and culture spilled onto the streets, the public realm too improved significantly, almost by default. Because all galleries could not be on Rampart Row, the inner lanes around the precinct developed with new boutiques, restaurants, corporate offices and galleries. It acquired its own momentum. The municipal authorities re-laid the roads and the pavement galleries. The area started getting cleaned up almost naturally; it became an active zone with lots of light on the street, alive and vibrant with reduced potential for crime.

Along the way, there have been a fair share of sceptics and critics, but the Kala Ghoda Festival (KGF) and its organisers have stayed the course.

They have created a festival that is truly a living, urban museum, spanning almost 1,10,000 sq. ft of existing indoor gallery space with an additional mass of outdoor pavement galleries on Rampart Row and potential exhibition space within the covered arcades. It has become an ‘address,’ a highly desirable piece of real estate for the art galleries, boutiques, cafes and restaurants in the area.

The traffic and civic issues still pose a huge challenge to the KGF. It would be splendid were they able to declare the area a pedestrian zone, and possibly make the fountains functional. But no one can deny that the KGF has successfully restored history amid the chaos of a metropolis, created an interest in the general populace for heritage walks and bus rides and instilled pride and ownership into the heart of the Mumbaiite.

Comments (0)