“Southern California attained a special valence because its dreams and metaphors stood so close to the surface of its material texture, like the schematized components of a successful stage set.” — Kevin Starr, Material Dreams.

Form Follows Film

Since the motion picture industry flowered there, Southern California has exported its fantasy to global audiences: a lifestyle of entertainment and leisure. In the early 20th century, this idea existed on film reels, but not necessarily as a built reality. Places across California emulated the cinematic promise with varying success, yet nowhere committed to it more than Santa Barbara. Over time, local history blended with popular culture, yielding a romantic origin story for the town and the good life associated with it. A consistent municipal campaign materialized Santa Barbara’s myth into a built environment, producing a vernacular hyper-reality. Santa Barbara therefore projected a city image epitomizing the Californian Dream before it ever appeared on the silver screen.

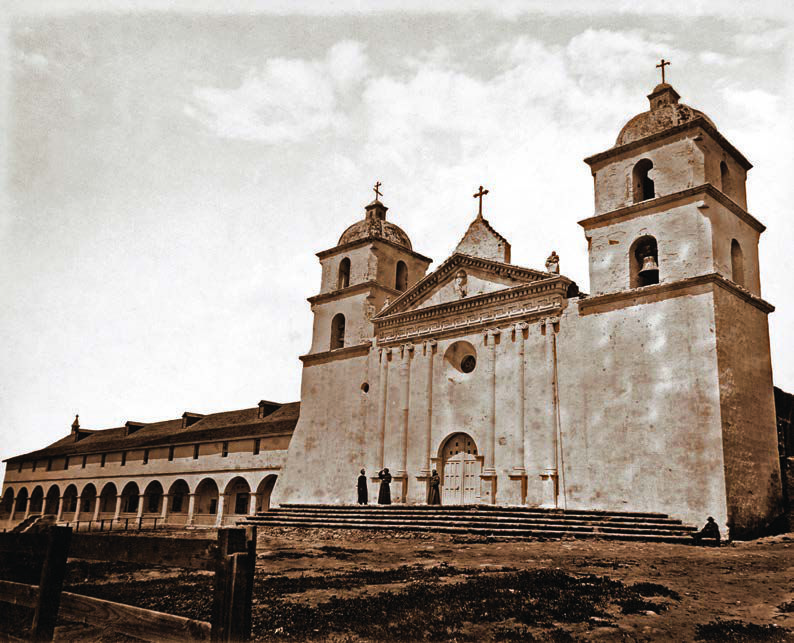

Photo: Carleton Watkins/Metropolitan Museum of Art. ©: {PD-1923}

The idea of Santa Barbara predates the film industry, but its urban expression doesn’t. In the golden age of silent films, movies were shot on mega-sets that often-melded exotic histories and geographies. Up the coast from Hollywood, Santa Barbara also combined authentic and invented Mediterranean traditions after an earthquake destroyed parts of the city in 1925. Architects rebuilt and reimagined Santa Barbara with the artistic vision of motion picture production designers, who at the time produced sets the size of entire neighborhoods. Santa Barbara thus realized a ‘stage set urbanism’, one best experienced with suspended disbelief. Liberated from academic skepticism, today one may enjoy its architectural escapism. The ahistorical romance saturating this cinematic city conjures a Mediterranean of the mind: the real, and unreal, Santa Barbara.

Writing Santa Barbara’s Screenplay

Like all good legends, Santa Barbara’s Hispanic origin story is based on truth. In the 18th century, Spanish missionaries founded it as a hub of mercantile and religious activity, connecting native Chumash villages to a vast colonial matrix. Santa Barbara had an architectural pedigree from the beginning: the monks designed their eponymous Mission after a copying Vitruvius’ work. A town grew around it, which eventually became a Mexican territory and later part of an American state. The West’s Hispanic past fascinated Americans, and novels such as Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona idealized it. The book, set in Santa Barbara during the Mission era, established the city’s popular association with Hispanic heritage.

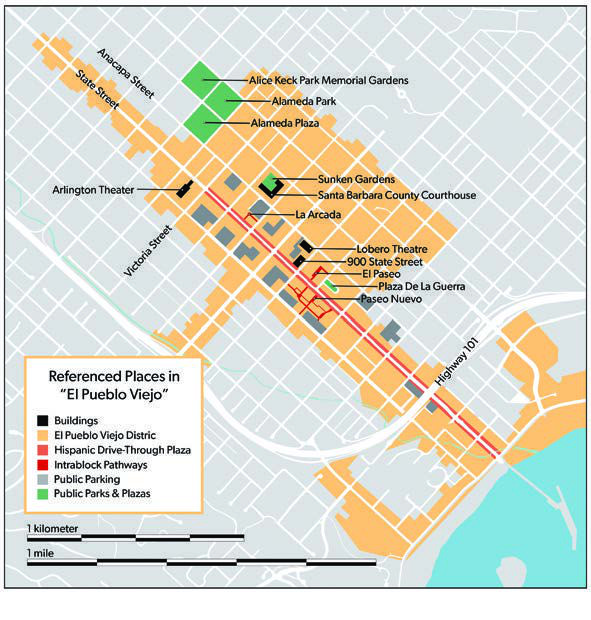

Source: Willem Swart

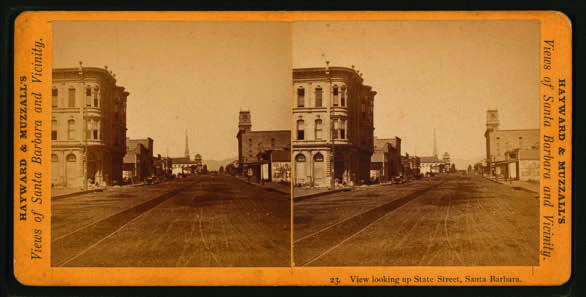

Photo: Hayward & Muzzall/New York Public Library ©: {PD-1923}

By the end of the 19th century, however, Santa Barbara didn’t look particularly Spanish. Victorian buildings, not adobes, became the architectural majority after California achieved statehood. When Yankees arrived in Santa Barbara, they brought wooden balloon-frame construction with them. The city grew and emerged as a destination for convalescents, who benefited from its favorable Mediterranean climate. A hotel industry developed to accommodate these recuperating visitors, establishing tourism as a key part of Santa Barbara’s economy.

Ironically, wealthy American newcomers, not the descendants of the rustic aristocracy depicted in Ramona, revived Santa Barbara’s Hispanic legacy. In 1909, the Civic League hired Charles Mulford Robinson to draft a master plan for Santa Barbara. Two of his recommendations are central to the stage set urbanism that subsequently arose. Firstly, he identified State Street as the major thoroughfare of Santa Barbara and urged its continued development. He noted that State Street was situated in the valley between mountains and a mesa, connected the hotel area to the railroad station and scenically terminated at Stearns Wharf on the Pacific Ocean.

So, the city encouraged the continued development of commercial, civic, religious and secular institutions around State Street, resulting in the vibrant avenue there today.

Crucially, industry was forbidden from locating there and actively discouraged in the rest of Santa Barbara. While this prevented it from becoming a big city (nascent movie studios and aviation businesses inevitably relocated), restrictions on industry preserved Santa Barbara’s genteel way of life and local leisure remained a tourist attraction. Robinson also argued that Santa Barbara should adopt its Hispanic heritage, evident in the Mission and De La Guerra Plaza, as the city’s controlling metaphor. City leaders accordingly invented an annual schedule of public events, like ‘Fiesta Days’, to promote Hispanic culture and boost tourism. However, the conversion of the built environment from Victorian to Spanish had to occur one building at a time.

All Photos: Willem Swart

Designing Santa Barbara’s Set

An earthquake ravaged Santa Barbara in 1925 but, luckily, human casualties were relatively few, and the devastation provided a unique opportunity to remake the city in the Hispanic image. By then, the Mission revival style had risen and receded in architectural prominence.

Despite its fidelity to local building precedents, Santa Barbara didn’t adopt the Mission revival style, choosing the more flexible and fashionable Mediterranean style instead. This revival movement included distinct historical subcategories as well as fantasy architecture, drawing inspiration from around the Mediterranean Sea and Spanish colonies.

These rapid changes occurred contemporaneous with the advent of the Hollywood dream factory. The Zorro film franchise captivated American audiences in the 1920s, just as the novel Ramona had in the previous century. Production designers erected large Mediterranean environments for other films, including Intolerance, The Sheik, The Ten Commandments and The Thief of Baghdad. These elaborate facades made cinematic narratives appear real through their imposing physical presence on camera. Likewise, Santa Barbara made its Spanish colonial story real by building it. And unlike a movie, which can only be seen, Santa Barbara can be lived. In the aftermath of the earthquake, Santa Barbara founded a formal Architectural Board of Review, the first in the nation, to strictly enforce the Mediterranean style across the city. The preservation of its set-designed built environment kept the dream alive, so in 1960 Santa Barbara designated 16 blocks of downtown as a landmark district: ‘El Pueblo Viejo’.

The style mandate may seem rigid, but there is considerable latitude within the Mediterranean genre. The Lobero Theatre, at one end of the architectural spectrum, opened the year before the big quake. George Washington Smith and Lutah Maria Riggs, a pioneering female architect, designed it as a model of Andalusian austerity. White and sparingly ornamented, the building is essentially pure volumes, not unlike the contemporary modernist architecture in Europe. In the following decades, Modernism became mainstream in America, and a Mission-Modern style emerged in Santa Barbara. The front façade of 900 State Street, originally a bank, is essentially a monumentalized Hispanic porch supported by huge piers. The building attests to a post-war Santa Barbaran identity crisis, in which architects tried to reconcile local building preferences with global design trends. This hybrid period ended with the advent of Postmodernism, yet counter to the prevailing architecture culture, Santa Barbara’s renewed historicism was ‘un-ironic’.

Through stylistic regulation, city officials curated a Mediterranean mélange on and around State Street, which also includes Churrigueresque, Italianate, Moorish, Romanesque, and even an adobe/streamline modern reading room. Each building represents an individual scene in the stage-set of Santa Barbara, the most celebrated of all being the Santa Barbara County Courthouse. Architecture historian David Gebhard considered it the Spanish Colonial Revival’s zenith for ‘its ability to realize theatrical and dramatic space.’

Completed in 1929 by William Mooser III, the richly detailed, U-shaped building frames the picturesque Sunken Gardens, one of the city’s most frequented public parks. From the clock tower, visitors have a panoramic view of the entire city, a sea of red roofs and white walls.

Staging Santa Barbara’s Production

Some critics deride the Hispanic revival as superficial, but such conclusions ignore the Spanish Colonial style’s spatial qualities.

In a traditional casa de rancho, the prominence of a central patio emphasizes the public realm and covered outdoor hallways blur the distinction between interior and exterior space. In Santa Barbara, this architectural logic is expressed in the urbanism. At the scale of the city, the patio becomes a plaza. Anchoring one end of the downtown district is Alameda Plaza, one of three contiguous blocks of green space (with the adjacent Alameda Park and Alice Keck Memorial Gardens). Further down Anacapa Street, which runs parallel to State Street, are the Sunken Gardens and De La Guerra Plaza. Additionally, there are public parks on the fringes of El Pueblo Viejo, where downtown transitions into residential neighborhoods. The plurality of green space in and around the landmark district provides scenes for relaxation, exercise and public engagement.

The most important plaza of all, however, is State Street. It was first paved as the city’s main thoroughfare in 1887, but incrementally transformed into a drive-through plaza in 1969. Starting at Victoria Street, traffic was narrowed into one lane in either direction for the addition of bike paths and widened sidewalks. The alterations accommodated more pedestrian amenities, such as benches, water fountains, planters and a tree canopy. Architect Robert Ingle Hoyt and landscape architect Julio Juan Veyna designed the first six blocks, envisioning an urban forest with meandering circulation. Later additions to the drive-through plaza vary, although they tend to be more orderly than Hoyt and Veyna’s project. It extends all the way to Stearns Wharf, but unfortunately continues underneath Highway 101. A local design committee executed the necessary freeway bridge as inoffensively as possible in the vernacular style. Beneath it, pedestrians are elevated above State Street on a protected pathway with a vaulted ceiling. If it were anywhere else, the highway might deter pedestrians, but the allure of the nearby beach keeps pedestrians walking underneath.

Perhaps the underpass functions because downtown already fosters unique urban spaces that pass through and around buildings. Official design guidelines for El Pueblo Viejo actively encourage (if not outright demand) the incorporation of street-facing arcades and alleys, resulting in highly permeable blocks that enrich the pedestrian experience. Passages such as El Paseo (James Osborne Craig, 1922) and La Arcada (Myron Hunt, 1926) are charming retail and restaurant destinations, decidedly more pleasant than shopping malls. In other instances, alleys provide a way for people to access their cars. Thus, buildings can surround parking lots on at least three sides, minimizing their negative urban impact. These intra-block paths elevate the pedestrian experience to the point that walking becomes a tourist attraction. Local architect Jeff Shelton refers to ‘god lines’ in his own work, ‘the lines of enticement that make you curious to follow a path through a gate or around the next bend.’ Santa Barbara’s passages do the same thing, enticing passers-by from the main street, winding them through the block and depositing them close to where they began. Such urban design is fun and easy for tourists to navigate, rendering smartphone maps obsolete. The networks of intra-block paths engender a condition of controlled discovery, where people can explore without ever getting lost. Like a stage set, the blocks of State Street are dense, but not deep.

|  |

All photos: Willem Swart | |

The Arlington Theatre, marking the beginning of El Pueblo Viejo’s core area, epitomizes the qualities of stage set urbanism. The building, designed by William Albert Edwards and Joseph Plunkett and finished in 1931, evokes the energy of performance through an exuberant Mediterranean style. It even sports a steeple capped with an Art Deco finial, a Hollywood gesture. The portico on State Street draws one inside with perspectival depth. On either side is an arcade and garden, so diffused light filters in through tropical foliage. A passage lined with shops and businesses connects the portico to the theatre entrance, blurring the distinction between interior and exterior, building and city.

The ultimate reveal, however, lies within. The auditorium is imagined as a complete Hispanic plaza flanked by Mediterranean architecture on all sides. These ‘buildings’ have ground floor arcades that function as theatre aisles and accessible second story wooden balconies. The curved ceiling above is painted with a trompe l’oeil starry sky. During the show, audiences feel as though they are watching an open-air production in a plaza.

The Arlington Theatre is therefore not a stenographic illusion in the manner of Sebastiano Serlio, but a real microcosm of Santa Barbara.

The Genre Endures

This building and the city entwine art, entertainment, history and fiction to realize a local authenticity. Santa Barbarans developed a screenplay for their city and produced a set to make the story real. This production design has continued for a century now, cultivating an endemic building tradition that transcends the label of revival style. Architects here don’t automatically translate architecture from Spain into Santa Barbara, they learn from and contribute to the built environment around them. The city evolved from a Mediterranean pastiche into a self-reflexive Mediterranea, giving rise to a local school of architectural practice. The city doesn’t pretend to be anywhere else; rather, Santa Barbara plays itself.

The invented city image may not be historically accurate, but it certainly makes narrative sense. Movie genres fade away when their conventions are no longer meaningful to their audience. Santa Barbara’s commitment to an architectural genre fulfils a romantic idea of California and its city image is an ongoing process. The key to Santa Barbara’s vitality and relevance is that it isn’t static. It’s had different periods of development and continues to change (at the time of writing, there are several construction sites on and around State Street’s Hispanic Drive-Through Plaza). Santa Barbara is a city of entertainment and leisure because it sustains dual natures: the real Santa Barbara, an evolving city, and the unreal Santa Barbara, a Californian Dream. It’s a place where residents live and work, and a destination that tourists visit. Santa Barbara is both a city for people’s lives and a stage set for their imagination.

Comments (0)