1st PRIZE WINNER - DAIDA GLOBAL AWARDS 2021

Ain Shams University, Egypt

During a pandemic, with climatic variability and uncertain future water availability, finding safe water is crucial to protect the health of families around the world and to secure the development of any human settlement. According to the World Health Organisation, globally there are 785 million people without access to basic drinking water services and by 2025, half of the population will live in water-stress areas. The Lima Metropolitan Area (LMA), the second biggest city built in a desert after Cairo, is already under water stress with only 125 m3/hab./year of water available and over 1.5 million people without access to safe water.

The problem

Rapid expansion and unreliable state services have increased the difficulties to sustain water security in urban and peri-urban areas of Lima, Peru. Moreover, water is inefficiently allocated, regressively priced and of limited access in the periphery, due to the lack of official infrastructure networks of the water utility Sedapal. These multiple layers of scarcity have increasingly affected the vulnerability of urban slums.

The research aims to highlight the diverse water delivery configurations of informal settlements from the peri-urban hillsides and their everyday practices when dealing with the absence of direct tap water networks. The study was conducted in three neighbourhoods from the Jose Carlos Mariategui (JCM) settlement in Lima East, which is a representative sample due to socio-spatial, ecological and technological factors.

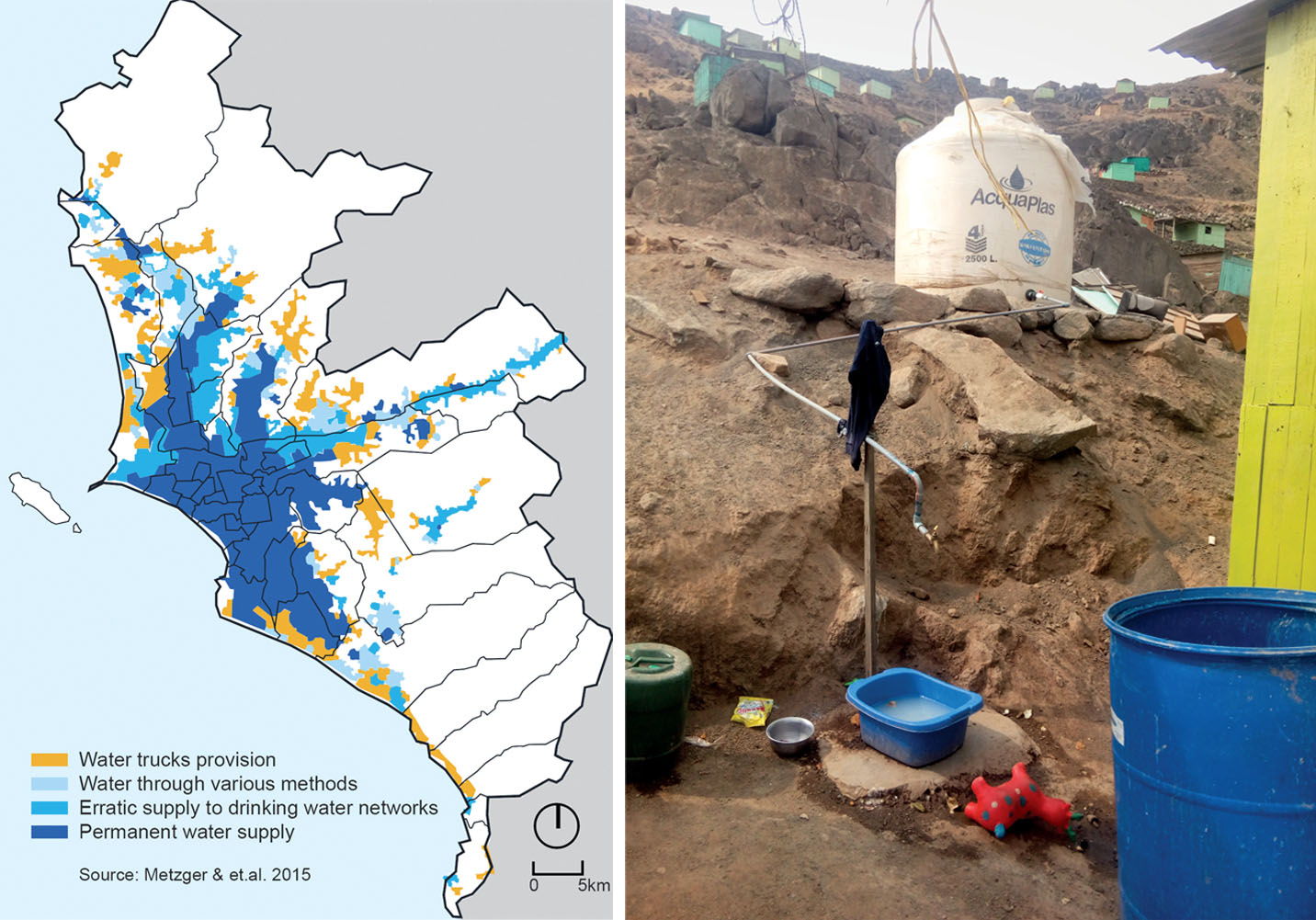

The water supply profile in Lima’s peri-urban slums

Multiple water delivery configurations

The understanding of the water supply practices in disconnected areas reflects on a framework of analysis that discusses spatial, managerial and techno-environmental dimensions. From this perspective, there are four main types of water supply co-existing in JCM: (1) The provision of ‘formal’ water infrastructure networks through State programmes, (2) Self-provision through water trucks, (3) Selling of water by neighbours with water and sewerage connections. (4) Public metered water standpipes from Sedapal. The latter composes the primary source of a community-led system, an example of a socio-technical arrangement, self-built and managed collectively. It aims to draw water progressively to households uphill and to reduce individual struggles of costs and time spent on the downhill collection.

Everyday practices for water access

These describe the adaptation strategies at the household and community level to secure daily needs. The most representative findings highlight the mechanisms of chasing alternative taps to cope with the irregular supply, solidarity behaviours between households or in-between communities, water-reusing practices, and contingency responses against water theft. At the community level, the transactions between seller and buyer reveal the managerial practices between the community leaders and Sedapal to negotiate for regular water standpipe supply.

Beyond formal-informal water service provision

It is argued that existing water supply systems in informal hillside areas draw from the interlinkages between formal-informal provisions. The ‘formal’ supply is the extension of public standpipes, regulated and operated by Sedapal, combined with ‘unofficial’ arrangements of community poly tanks and hoses adapted to the topography. Formal rules of water utility coexist with informal norms, structures and patterns of behaviour. It demonstrates that this hybrid system displays organisation in progressive water access with valued attributes of formality. These findings correlate with academic studies on fluid formal-informal waterscapes and water governance capacities of the water-poor in cities of the Global South.

Right: Everyday practices for chasing alternative taps

Water access sustainability

The research sheds light on the existent hybrid provision and analyses the access sustainability of the community-led scheme through their socio-technical, organisational, economic, socio-cultural and environmental aspects.

Overall, the scheme builds upon organisational-institutional arrangements for distribution, regulation and maintenance. It is positioned as a low-cost unofficial technology against water insecurity. The logic for collective gain is limited to the financial independence of the community, lack of alternative water sources and erratic water standpipe supply. The underlying effects on the occupied ‘Lomas’ ecosystem and human health are also evident if urban expansion and inefficient water disposal continue.

Proposed short-term measures capitalise on the strength and limitations of community-based organisations (CBO) to trigger a direct impact on their livelihoods. For instance, enhancing the community capabilities, promoting a coordinated vision for structural urban change and developing alternative water sources that encourage productive waterscapes as a source of income for residents. Moreover, recommendations at a medium scale pay special attention to the awareness of untreated wastewater and water-sensitive prototypes that encourage the recycling discipline into safe reusing methods.

Formal rules of water utility coexist with informal norms, structures and patterns of behaviour

Policy implications

It seems necessary to bridge the gap between the State and the CBO for planning comprehensible water and sanitation services of disconnected neighbourhoods. The State programmes for the extension of water networks have encouraged further expansion of informal areas while promoting a political clientelism approach. The acknowledgment of heterogeneous systems within water policies requires strengthening the capacity of private, public and community actors to improve stewardship and help to delineate sustained interventions that go beyond supply augmentation. Policies must call for broader discussions in the crosscutting links of safe land tenure that echo in the manifestation of inequalities such as affordability and irregularity issues.

Conclusions

The research seeks to contribute to the academic debates on water delivery configurations in the global south. It outlines opportunities for planners and policymakers of a long-term sustainable solution to invisibilised urban water delivery configurations, overshadowed everyday doings for access to water in informal areas and urban waterscapes that shape and are being shaped by the socio-spatial organisation of the settlement. The heterogeneity of service provision in informal settlements in hillsides exposes a hybrid provision that exceeds statutory-conventional piped water systems. Thus, further study of sustainable pro-poor alternatives that encompass the formal-informal interlinkages and water governance capacities is required.

Comments (0)